I had just turned 36 when it happened. Two weeks after giving birth to my second child, a beautiful baby girl named Aurora, my husband and I were leaving a check-up with her pediatrician when I suddenly started to overheat. The late summer weather was sweltering, but this was something else. Instantly, I was drenched with sweat. My chest tightened and I was gasping for air. The pediatrician's office was just one floor up from the parking lot, but the elevator ride felt infinite. As soon as the doors opened, I bolted to the car.

Breastfeeding hadn't been working—Aurora was having difficulty latching on, so while I was producing a lot of milk, she wasn't getting the nourishment she needed. In an attempt to halt my milk production, I'd been tightly wrapping my chest with an ACE bandage. I assumed the tension I felt was the result of milk backing up in my breasts beneath the binding; I just needed to free myself from the constriction.

I tore the wrapping off my body, but continued to struggle for air. My jaw started to ache, and the crushing tightness spread to my throat. I had an appointment scheduled that day with my OB, so we drove to the office, where the doctor decided the symptoms were indeed related to my breast-milk production, maybe a clogged duct. "Try to get milk out if you can," he said. "If it happens again, give us a call." I pumped throughout the day and felt fine. By the next night, my milk supply had significantly dwindled.

But then the symptoms struck again.

I assumed the chest tension was the result of milk backing up in my breasts beneath the binding; I just needed to free myself from the constriction.

This time, in addition to suffocating heat and chest tightness, pain radiated down my left arm. My husband sat with me until it subsided, but when I woke up a few hours later to feed Aurora, I didn't trust myself to hold her; I felt too weak.

I drove to the emergency room alone and terrified while my husband stayed home with the kids. An EKG came back normal. The doctor said symptoms could be due to swelling of the heart—a rare but treatable peripartum condition. It was the first time I'd even considered that my heart could be the culprit.

A blood test revealed my levels of a protein called troponin were off…something was wrong, but the doctors couldn't diagnose it. They wanted me to stay overnight to see a cardiologist. I contemplated leaving—my symptoms had waned and it was heart-wrenching (word choice intentional) being separated from my newborn—but I needed to know what was happening to my body.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

The hospital staff were just as confused as I was. I was young and healthy with no known history of heart disease in my family. Nothing made sense and I felt completely alone.

When a medic arrived to transport me to my next test, he stopped dead in his tracks, visibly shocked to find that his heart patient was a mid-30s mom. "It must be the breastfeeding thing," he said after I relayed the story. "It can't be anything else." I felt horrible: Was it all in my head?

While I worried, doctors inserted a flexible tube into a small incision in my arm and threaded it all the way to my heart. I was heavily sedated, but I wasn't fully out—and to add insult to injury, I woke up too soon, forcing the doctors to end the procedure prematurely. They'd have to go in and do it again.

When the medic arrived to transport me to the other facility, he stopped dead in his tracks, visibly shocked to find his heart patient was a mid-30s mom.

They'd just placed two stents (mesh tubes that open up narrowed arteries) when a different blood vessel began to show signs of trouble. And then another. And another. The doctors quickly realized this wasn't a buildup of plaque—this was a tear. I had an affliction called Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection, or SCAD. And what I'd experienced a few days before? The pain in my chest? That was a heart attack.

I had never heard of SCAD, let alone thought I was at risk for it. It's a sudden tear that forms in one of the blood vessels in the heart, which slows down or totally blocks blood flow. Sometimes stents are used to open up the narrowed vessel, but in some cases, like mine, stents can actually make the problem worse. Luckily my doctors realized they needed to stop using them during my procedure. I later learned I was lucky in an even bigger way: SCAD not only causes heart attacks—it can also cause sudden death.

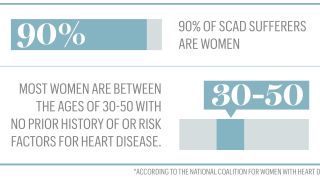

I didn't understand. How could my heart have torn? It turns out, I'm a textbook SCAD victim: Between 80 and 90 percent of SCAD sufferers are women and, according to The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease, most are between 30 and 50 with no prior history of or risk factors for heart disease. "If you look at the proportion of young, healthy women having heart attacks, a third to half of them are having coronary artery dissections," explains my current doctor, Jennifer Tremmel, M.D., an interventional cardiologist and assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine at Stanford University Medical Center. The reason: A major risk factor for SCAD is being a new mom.

A major risk factor for SCAD is being a new mom.

Dr. Tremmel says heart attacks occur for approximately 1 in 16,000 pregnancies in the U.S. It's an undeniable association that experts are struggling to make sense of. Many speculate that the spontaneous tearing is due to some kind of hormonal shift, but there's not enough research to back it up. And while there are reports of women having chest pain or experiencing SCAD during breastfeeding like I did, it's not clear whether those things are directly connected. Dr. Tremmel and her colleagues are currently working on an international study to compare cases of SCAD in women who'd recently given birth and those who hadn't to see if they can tease out differences between groups. The results will be out later this year.

Until experts know more, I'm urging women to get familiar with the signs of a heart attack and to accept that they're at risk. "When I give talks, I have to remind people that you cannot profile a heart attack victim," Dr. Tremmel says. "We've done a disservice by only ever showing heart attack victims as old, fat guys. It makes everyone else think they're fine." It's important to know that the symptoms may not mirror what's depicted in pop culture: people clutching their chest and falling to the floor. For women, it's much more common to experience chest tightness, sweating, an aching jaw, shortness of breath, and pain in the left arm, like I did.

After my angiogram, I was fortunate to go home. The tears eventually healed on their own and I've been able to stay healthy by taking a few medications to regulate blood pressure and heart rate, getting 30 minutes of physical activity a day, and watching my diet. I survived with no permanent heart damage, which I consider a miracle, but no one knows for sure if I'm completely in the clear. Dr. Tremmel says patients who've had SCAD have a 30 percent chance of recurrence over a 10-year period. No one knows for sure if certain risk factors (like pregnancy) can impact this, so my husband and I decided we wouldn't have any more children in order to avoid the risk.

Sure, SCAD is rare, but women need to understand that they may be at risk. They need to know the signs, and to value themselves enough to get help fast. SCAD is a heart attack, so if you feel something strange, call 911. Educate yourself. And make sure all of your doctors, including your PCP and OB, know about SCAD—many don't.

As women, we often get so caught up in tending to everyone else's needs that we overlook our own. But when it comes to SCAD, trusting your instincts and listening to your body can literally save your life.

Follow Marie Claire on Facebook for the latest celeb news, beauty tips, fascinating reads, livestream video, and more.

-

Hugh Grant Is More Than Ready for the Next 'Bridget Jones' Movie

Hugh Grant Is More Than Ready for the Next 'Bridget Jones' MovieThe fourth movie might just be the best of the entire series.

By Meghan De Maria Published

-

The Best Looks Spanning Zendaya’s Style Evolution

The Best Looks Spanning Zendaya’s Style EvolutionShe's long been a beacon of support for emerging designers like Peter Do. Now, the actress is not just breaking the internet with custom Loewe and archival Mugler, but also inspiring a new wave of fashion enthusiasts.

By Lauren Tappan Published

-

Which Zendaya Era Reigns Supreme?

Which Zendaya Era Reigns Supreme?Zendaya's lived a dozen lives when it comes to her career, from her Disney days to music video star to the MCU. Here, we provide our definitive ranking of her best onscreen performances.

By Andrea Park Published

-

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"Senator and breast cancer survivor Amy Klobuchar is encouraging women not to put off preventative care any longer.

By Senator Amy Klobuchar Published

-

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My Body

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My BodyI'm plus size, but after I decided to pose nude for photos, I suddenly felt more body positive.

By Kelly Burch Published

-

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?Much like abortion, surrogacy, and IVF, becoming an egg donor was a reproductive choice that felt unfit for society’s standards of womanhood.

By Lauryn Chamberlain Published

-

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in Check

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in CheckGut health = wealth.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo Olympics

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo OlympicsShe withdrew from the event due to a medical issue, according to USA Gymnastics.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Truth About Thigh Gaps

The Truth About Thigh GapsWe're going to need you to stop right there.

By Kenny Thapoung Published

-

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” Condition

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” ConditionDespite having no outward signs, they can be brutal on the body and the mind. Here’s how each woman deals with having illnesses others often don’t understand.

By Emily Shiffer Published

-

The High Price of Living With Chronic Pain

The High Price of Living With Chronic PainThree women open up about how their conditions impact their bodies—and their wallets.

By Alice Oglethorpe Published