The Dawn of the "Career Girl"

In an excerpt from Brooke Hauser's new biography, Enter Helen, iconic editor Helen Gurley Brown radically advocates for young women to have jobs, sex lives, and money of their own.

A few months before Playboy's April issue hit stands, a young journalist from Ohio applied for one job that Helen Gurley Brown never could have landed, no matter how hard she tried: Playboy Bunny. Even with her wigs, false eyelashes, Pan-Cake, and padded bra, Helen simply didn't look the part. But Gloria Steinem did. Twenty-eight with dark brown hair, kohl eyes, and the killer legs of a Copa Girl, Steinem walked into Hugh Hefner's New York Playboy Club one brisk day in January 1963, carrying her leotard in a hatbox and a newspaper ad hyping the perks of being a Playboy Bunny: celebrity encounters, travel, and "top money."

Pretending to be a former waitress named Marie Catherine Ochs (a family name), Steinem told the woman who interviewed her that she had come to audition to work at the club. Indeed, she had, but her real mission was to go undercover as a Playboy Bunny and write about the seamy reality of the job for Show, a stylish monthly magazine covering the arts.

Steinem ended up training and working as a Bunny for about three weeks. Like the other women on her shift, she donned her cleavage-baring costume with its collar, cuffs, and tail, perfecting her Bunny dip. Unlike the other Bunnies, she also took notes about the job's not-so-glamorous demands: grueling working conditions, a demerits system that left many girls broke, and the disturbing requirement that all Bunnies get a gynecological exam by a Playboy doctor.

The first installment of her witty, groundbreaking two-part series, "A Bunny's Tale," ran in Show that May, followed by the second installment in June. And while the exposé was an instant sensation, it also created lasting problems for Steinem. Hours upon hours of wearing high heels and carrying heavy trays permanently enlarged her feet by half a size. Long after she turned in her costume, Playboy continued running her employee photograph out of spite. (In 1984, Playboy ran a different photo of Steinem, at age 50, in which her breast was accidentally exposed.) In some circles, she became known as just another Playboy Bunny rather than as a serious journalist who had gone undercover for an assignment. It would be years before she felt proud of the article, realizing that, as she put it, "all women are Bunnies."

The working woman was just the outcast du jour.

While Gloria's star was rising in New York, another journalist was igniting a new movement among women. Barely over five feet with salt-and-pepper hair, heavy-lidded brown eyes, and a nose that got her teased as a kid, Betty Friedan might as well have strapped a ton of dynamite under her housecoat: Her book The Feminine Mystique exploded onto the scene in February 1963, blasting a hole into the image of the happy housewife. Millions of women had fallen victim to an empty notion of femininity propagated by companies selling everything from washing machines to face creams, she argued. Marrying and having kids younger, they felt trapped in their homes, in their sex lives, and in their own bodies; and they grappled with an existential dread that she called The Problem That Has No Name.

"It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States," she wrote. "Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—'Is this all?'"

The Feminine Mystique began with a question—"Is this all?"—and ended with a plan of action. The last chapter was titled "A New Life Plan for Women." Women needed to stop pretending that housework was a career. "The only way for a woman, as for a man, to find herself, to know herself as a person, is by creative work of her own," Betty Friedan wrote. "There is no other way."

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Several months later, Friedan's message embedded itself into Helen Gurley Brown's consciousness as she was writing and revising Sex and the Office. "I'll tell you this," Helen typed, addressing the legions of unhappy housewives, newly outed. "Women in offices never have to wonder who they are. They know who they are, and nobody lets them forget it!" A career girl didn't have to search for her identity, she argued: She was the secretary, the actress, or the executive. People needed her and depended on her.

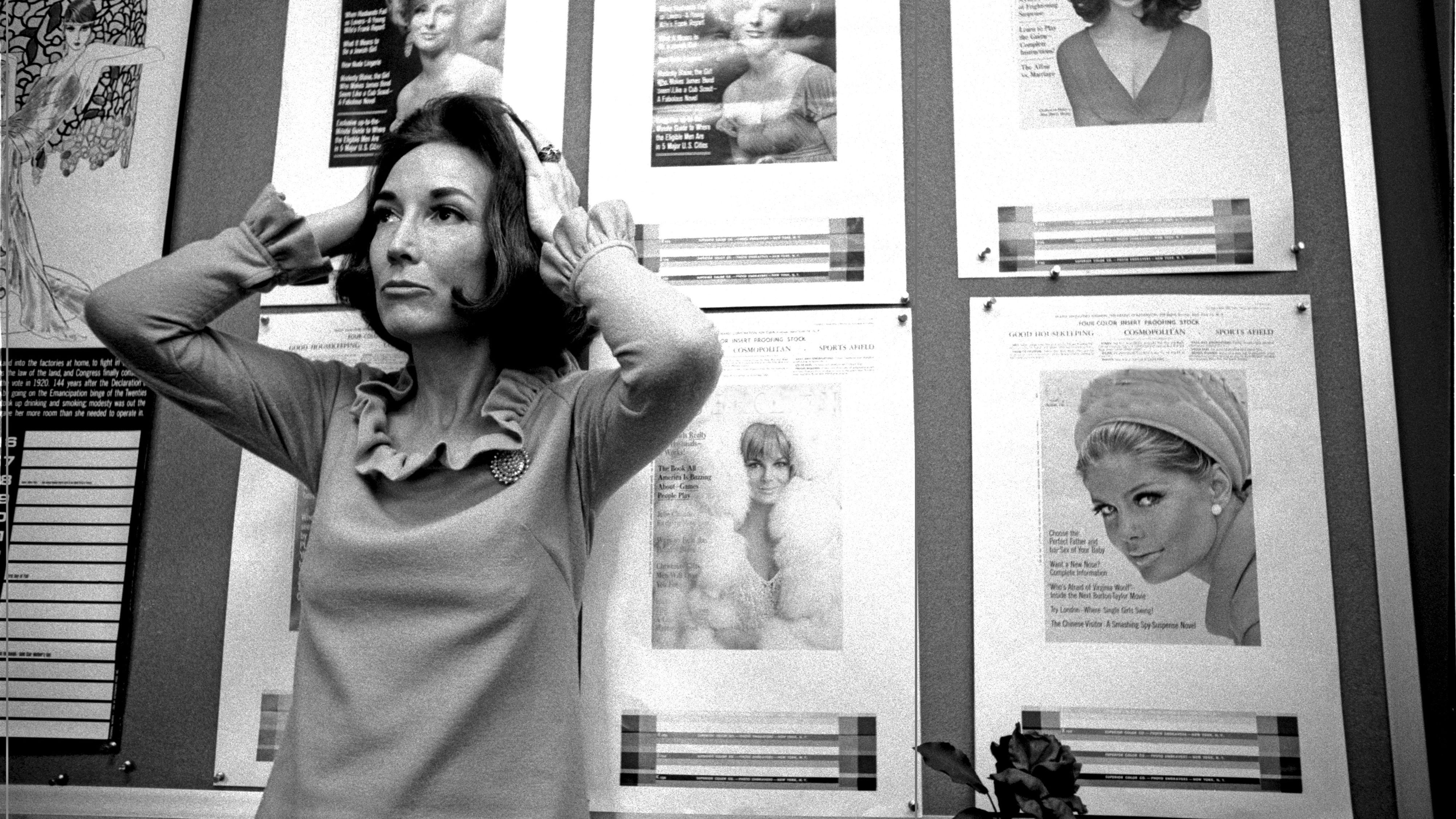

Helen at home on Park Avenue in 1965, with her cats, Samantha and Gregory. Copyright © I.C. Rapoport

But they also judged her. In 1963 the career woman was as maligned as the single girl had been two years before when Helen started writing Sex and the Single Girl. Helen had been looking for something to rail against, and she found it in the advice of Dr. Benjamin Spock, who suggested that working mothers were doing a disservice to their children; in the housewife who snarled over the career girl's success; in the working girl who dropped her job as soon as she found a husband; and in the blatant misogyny of writers like Philip Wylie, who authored a vicious article, "The Career Woman," for Playboy's January 1963 issue. "They call her brilliant, this highly paid Circe," Wylie wrote. "If she is, however, she is also, outside her career, more ignorant than institutionalized Mongoloids. . . . On her throne she sits, this skirt-girt squid, the she-tycoon, caring only about herself and heedless of the damage she is doing to the national psyche." (Two decades earlier, in his 1942 book, Generation of Vipers, the woman-bashing Wylie blamed society's ills on "momism," a term he coined to describe the phenomenon of American mothers smothering and emasculating their sons.)

The realization that the career girl was the new single girl hit Helen like a rolling metal filing cabinet. The working woman was just the outcast du jour. Helen felt her plight deeply, the unfairness and the injustice of it, but she knew she had to be careful not to sound scolding, or else another Philip Wylie would come along and lump her in with the rest of the shrieking she-wolves. She had to be subtle. And witty. She had to make people laugh before they would listen. So, she wrote a little riddle.

Beyond instructing office girls how to flirt—she wanted them to soar.

"We haven't been introduced though I may have been pointed out to you at parties," she began. It's likely that she was talking to a group of men, and that the person doing the pointing was a woman, gossiping with a gaggle of other women. "I might as well stop playing 'I've Got a Secret' and tell you who I am!" Helen wrote. "I'm one of those driven, compulsive, man-eating, penis-envying, emasculating, lacquered, female wolverines known as a career woman. Frankly . . . I've been about as much in vogue in recent years as rattan bedroom furniture. Rosalind Russell used to play me in movies of the '40s, but nobody wants to play me anymore."

In her signature, snappy style, Helen went on to list 24 reasons why women should work, suggesting that instead of becoming professional housewives they consider becoming psychiatrists, nurses, schoolteachers, social workers, and medical professionals, as well as entering fields monopolized by men, like physics and engineering. The chapter "Come with Me to the Office" was a clear invitation to women to follow her up the ladder, one rung at a time. Helen wanted it to be her first chapter, but it landed on Berney's desk with a thud. He was all for the sections on how to catch a man in the office, but for the most part he thought Helen was wasting space encouraging girls to get ahead in their careers. One day, he suggested, she could write a separate manual for the really ambitious girls.

"Most girls—probably 90 percent—who work in an office are not pyramid-climbers," he told Helen in a letter. "You happened to belong to the 10 per cent."

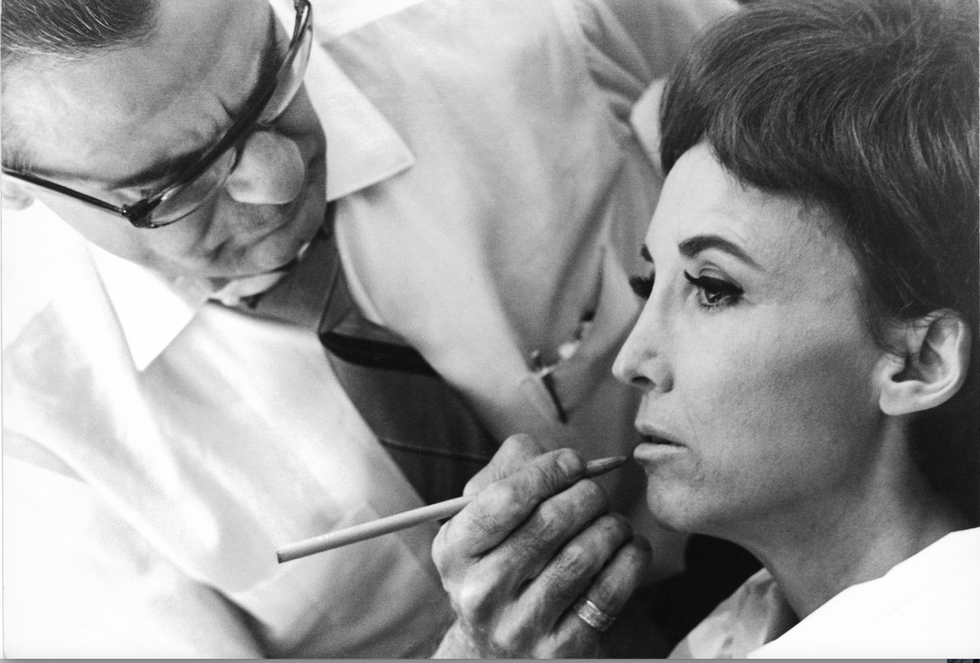

A rare behind-the-scenes glimpse at all the hard work (and makeup) that went into being the public Helen Gurley Brown. Copyright © Ann Zane Shanks

But Helen argued right back. She was willing to tone down that chapter, not to lose it entirely. The book needed a cause beyond instructing office girls how to flirt—she wanted them to soar. The typical working girl felt sorry for herself, just as the single girl had before, she pointed out to Berney. She was all of 18 when she took her first job at KHJ radio station in Hollywood to pay off her tuition for business college. She worked because she had to, because she didn't have a choice, and at first it felt like just another punishment that poor girls had to endure. It wasn't until she landed at Foote, Cone & Belding that she found her calling and a boss who was willing to take a chance on her as a copywriter. And where would she be now if not for that chance?

"Tell her she not only isn't unfortunate to be working but has the best of all possible worlds," Helen pleaded with Berney. If he insisted on cutting all the getting-ahead-in-a-career stuff, the book would lose its mission, and she would be stuck as a crusader without a cause.

I'm one of those driven, compulsive, man-eating, penis-envying, emasculating, lacquered, female wolverines known as a career woman.

Maybe it had something to do with the phenomenal success of Betty Friedan's bestseller, but more and more, Helen Gurley Brown, champion of the single woman, began to set her sights on attracting the married woman she had once mocked. It was time to stamp out the idea that the career girl suffered from some incurable illness that would derail Mother Nature's plan for her to procreate. A woman's fulfillment outside of the home was good news for the whole family.

In a chapter called "Come Back Little Wives, Widows, Divorcees," Helen made a special plea to the Little Wives to join the working world: "Explain to your husband, if he doesn't already understand, that you will be a better companion, a more adoring wife and loving mother if you are allowed to take a job," she advised. "Don't you see that by working you could have it all?"

But Helen wanted no less, and she didn't have to look far to find a poster girl for the glamorous career woman. In the spring of 1963, newly pregnant and still as chic as ever, she was on TV almost as frequently as her husband, whom she might not have met if not for her job.

Jacqueline Bouvier was 23 years old when she began working for the Washington Times-Herald newspaper as "The Inquiring Camera Girl," a reporting gig that paid her $42.50 a week to interview and photograph notable people around the city, including Richard Nixon. Granted, her questions weren't exactly hard-hitting. In 1952 she asked six housewives if they thought that Mamie Eisenhower's bangs would become a nationwide fad. Shortly thereafter, she met a soon-to-be senator named John F. Kennedy, whom she featured in her 1953 column and married the same year. Ten years and two kids later, she had one of the most important jobs in the world as first lady of the United States. How was that for having it all?

From Enter Helen: The Invention of Helen Gurley Brown and the Rise of the Modern Single Woman, copyright ©2016 by Brooke Hauser. Reprinted by permission of Harper, Inc.