What It's Like to Die Online

Chronically ill women are turning to YouTube to share their lives—and deaths.

“I have tried filming this video so many times, but I just don’t know what to say.”

Fifteen-year-old Sophia Gall has cancer, but from her hairless head and the title of the video, “My Cancer Is Worse Than Ever,” we already knew that. The problem is that there’s nothing left that can be done. Gall makes the announcement on her YouTube channel in an eight-minute vlog that has been watched more than a million times since it was posted in May 2017. The Australian teenager, an otherwise sunny, ebullient girl with cornflower blue eyes, is sitting in front of a camera on her pink bed, wearing a knitted beanie, sobbing.

Gall has been battling a rare form of bone cancer since June 2015. She thought she was doing better, but her most recent scans did not go well. The cancer has spread down her leg, and the doctors say it’s too aggressive to fix with chemotherapy and radiation. “I’m just going to go on a big holiday around the world and try to enjoy my life as much as I can,” she tells the camera, her freckled face collapsed, “because I don’t know how much longer it’s gonna be.”

Gall has been uploading YouTube videos about her life with cancer since a few months after she was diagnosed. In the two years since, she’s gained more than 145,000 loyal subscribers. They flock to the heartbreaking video, leaving comments about how brave she is and messages to stay strong. Gall’s next four weeks of content are much cheerier: She squeals at the Eiffel Tower, delights in a New York City shopping spree. Aspirational travel videos are a dime a dozen on YouTube, but these videos are different—the girl in front of the camera is dying.

InIt’s a phenomenon unique to the social media-centric era we live in—an era when even cancer is content.

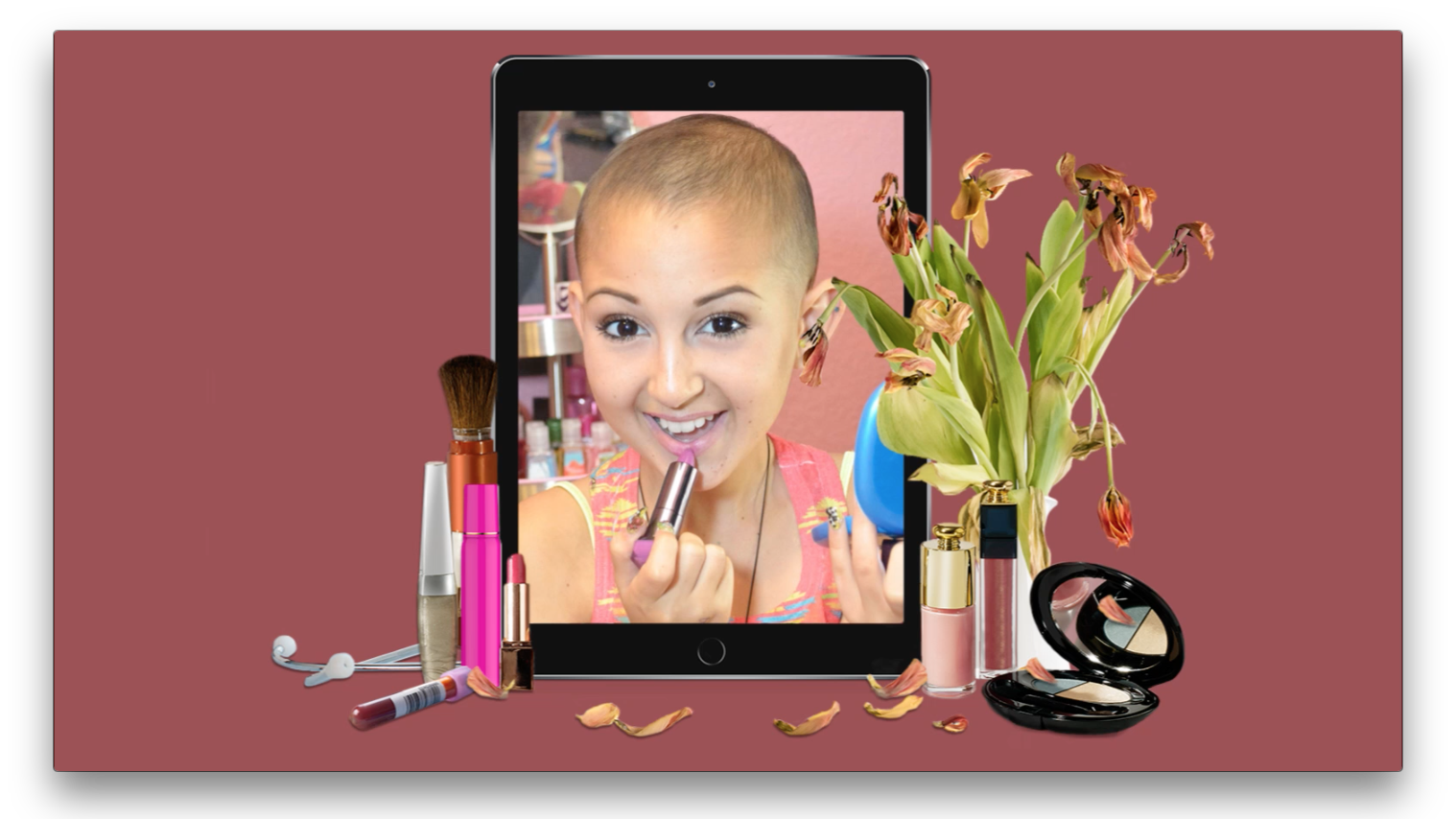

A growing community of young vloggers use YouTube to chronicle their journeys with serious illnesses from diagnosis to hospital visits to sometimes getting very bad news. Arguably, the most famous of these content creators was Talia Joy Castellano, a vivacious beauty YouTuber who died of cancer in 2013 just a month before her fourteenth birthday. Over her two-year YouTube career, Castellano gained 1.4 million subscribers who watched her battle neuroblastoma (a progressive tumor of the nervous system) while falling in love with her lively makeup tutorials and precocious sense of humor.

“This is beyond reality television. It’s real life, with life and death consequences,” says mental health expert Scott Dehorty, a social worker and therapist in Maryland. It’s a phenomenon unique to the social media-centric era we live in—an era when even cancer is content, when you can love, lose, and mourn a person you only ever knew through a screen.

When Castellano first started her channel, becoming a “cancer vlogger” wasn't her intention, she simply wanted to talk about makeup. Following her diagnosis, a family friend taught Castellano how to decorate her face with colorful eye shadows and lipsticks as a distraction. She came to love watching makeup tutorials. “Eventually she thought, ‘You know what? I could do this. I’m good enough to do what they do,’” says Castellano’s mom, Desirée. In 2011, the pre-teen began uploading her own bubbly tutorials and haul videos, which she’d film and edit on her laptop in her bedroom. It wasn’t until Castellano’s budding viewership began asking personal questions—why she didn’t have hair, for example—that she decided to talk about her disease. “She started raising awareness for childhood cancer through her videos, and the channel blew up,” recalls her sister Mattia, now 23. By 2012, her influence as an advocate landed her an appearance on The Ellen DeGeneres Show and she was named an honorary CoverGirl by the cosmetics company.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

“Every morning I would wake up in the hospital with nothing to do. I'd basically just spend my day watching other people on YouTube,” says Gall of the impetus for her channel. “Eventually I thought, What would be so hard if I made these videos?”

“When you see somebody whose battle is so over-the-top, so beyond what you've experienced, you realize that you can get through your own struggles.”

Mary Dalton was diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare childhood bone cancer, the summer before her freshman year of high school in 2015. She started vlogging about her cancer journey later that year. “I’d always been interested in YouTube, and when I got sick I was really lonely and didn't have a lot of ways to reach out to people,” she explains, adding that she was inspired by Talia Castellano. Filming and editing quickly became a fun and productive activity for Dalton to focus on during tough stretches of treatment. “Working on my videos gave me a routine,” the now-17-year-old says. “It was therapeutic.”

For Racheli Alkobey, who found out she had Hodgkin’s Lymphoma as a senior in college in 2015, the instinct to share her experience online was immediate—she started filming her first YouTube video the day she was diagnosed. “I just whipped out my phone,” she remembers. Alkobey’s first cancer vlog opens on a shot of her face lit by neon lights, a cheerful pop song thumping in the background. “So I’m bowling with friends…. Today was the day I found out that I have Hodgkin’s Lymphoma,” she tells the camera through a bewildered, anxious smile. “I’m a little bit in shock, but I have the most amazing friends.” The rest of Alkobey’s video cuts to clips of her running errands with her pals, starting a new raw food diet, driving to the airport to catch a flight to meet with a hematologist. The vlog, titled “The Day After My Diagnosis with Cancer,” ends with an image of Alkobey snuggling in bed with her best friend. “Everything’s gonna be okay,” she says with a hopeful grin.

At the time this video was posted, Alkobey saw YouTube simply as a convenient way to keep her friends and family updated on her health; and hopefully, her vlogs would reach a few other young people with cancer, giving them something they could relate to. Before long, however, Alkobey’s videos...and Dalton’s...and Gall’s would come to mean more to their subscribers, and to their own lives, than they could have imagined.

When asked why she thinks strangers were so attracted to the story of a terminally ill kid, Castellano’s sister Mattia says that, “Talia gave people hope. To watch this little girl who is dying have such a positive attitude was just captivating.” People struggling with cancer or clinical depression or even something as quotidian as a breakup would leave comments for Castellano, letting her know how much she helped them. Dalton has noticed that watching her videos seems to make viewers feel better about their own lives. “When you see somebody whose battle is so over-the-top, so beyond what you've experienced, you realize that you can get through your own struggles,” she says.

That sense of perspective is helpful, even necessary, for viewers. “Many girls worry about a bad hair day,” says Peg O'Connor, Ph.D., a behavioral health expert and professor at Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota, “but there’s a huge difference between a bad hair day because your bangs are too long and a bad hair day because clumps are falling out.”

Amid the whirlpool of reactions that come with receiving a cancer diagnosis is a feeling of inexplicable chaos, like your life is happening at random, and there’s nothing you can do about it. The ability to positively impact their followers makes the experience feel less senseless. “It helped me feel like the hard times were counting for something, that they weren’t just happening for no reason,” Alkobey says.

“There’s a huge difference between a bad hair day because your bangs are too long and a bad hair day because clumps are falling out.”

Equally empowering has been the simple act of taking their stories into their own hands. For the patients who are still minors, the decisions being made about their health aren’t entirely up to them. Creating videos is one way of maintaining some control. As Dalton describes, “Even though there were so many terrible things happening, with YouTube, I could make the terrible things into a video, into art. I could share it with people in my own way. That helped me cope.”

Dalton films her videos on a DSLR camera, and the footage is crafted with jump cuts, close-ups, music, and narration. Her films have an artistry to them—an intention. Videos like Dalton’s allow the creator to gain “autonomy and agency,” Dr. O’Connor observes, and the viewers get to see a full-blown individual, not a bedridden invalid. “The young people in these videos emerge as interesting, thoughtful, typical teenagers, who have some of the same concerns as others who are not sick,” she says.

Claire Wineland, a 20-year-old woman battling cystic fibrosis, lives on her own in Los Angeles, is financially self-sufficient, and runs her own foundation called Claire’s Place, which offers support to families living with CF; it’s important to Wineland that her viewers witness this. “You never see sick people as functioning humans doing something with their experience of being alive,” she says. “Yes, I have a terminal illness. But does that mean my life can never amount to anything? It’s really important for sick people to know: You're more than just someone sitting around waiting for your body to fail.”

Of course, no matter how sick you are, how much sympathy and compassion you deserve, internet fame inevitably comes with negativity. While the majority of comments are supportive, these women do receive hate. Galls remembers a comment suggesting she was faking her illness and that she should go to jail for what she was doing. “I wish that were the truth,” she says.

Raigda Jeha, a Canadian makeup artist and terminal stomach cancer patient, was given only three months to live when she was diagnosed in 2015—she has been managing her illness holistically and creating uplifting vlogs about the experience since. But when she put up her first video, a guy commented, “‘Why are you so worried about your makeup? You're dying,’” she recalls. “And then you get the trolls saying, ‘I have a cure! Buy this!’ Or people getting upset with me for pushing alternative medicine, which I’m not.”

There's also immense pressure to post regularly. “When you get big on YouTube, you're dancing with the devil a little bit,” says Wineland. “In order to keep up views and give people what they want, you have to produce a lot of content, and it’s hard to make meaningful videos when you’re posting so much.” At 17, Wineland launched her CF-awareness YouTube channel—featuring videos such as “What It’s Like to Be in a Coma” and “Dying 101”—and the teen’s exuberant personality and dark humor quickly earned her almost 200,000 subscribers.

“If you Google my name, the top thing to come up is ‘Is Claire Wineland dead?’ Which, I mean, is understandable.”

But in 2016, Wineland went about a year without uploading due to a squabble over ownership of her account (she initially hired a company to edit and manage her videos). Because viewers like Wineland’s are so invested in these stories—which are higher stakes than most—panic strikes when accounts go un-updated. Wineland recently launched a new version of her channel (which she owns and manages herself), but click on any of her old videos, and you’ll find dozens of comments asking what happened to her. “If you Google my name, the top thing to come up is ‘Is Claire Wineland dead?’” she says. “A lot of my followers think if I’m not posting, I’ve died. Which, I mean, is understandable.”

For sick YouTubers, the obligation to respond to the hundreds of daily comments from viewers—some of whom are seeking serious health advice—can be overwhelming. At 43, Jeha is part of a smaller faction of cancer vloggers from a different generation, a generation that didn’t grow up with screens. For them, the attraction is often as much about exchanging information as it is about seeking an emotional connection, explains Dr. O’Connor. Inspired by how proactive and knowledgeable Jeha was about her illness, a friend encouraged her to start her channel as a way to help other patients. In contrast to Mary Dalton’s highly curated videos and Racheli Alkobey’s action-packed vlogs, Jeha’s videos are simple—she films on her phone, selfie-style, with minimal editing. In them, Jeha is usually seated, casually chatting to her viewers about what foods and treatments have been working for her lately. She advises curious viewers to do research and take an active role in their own treatments.

Like the people they’re watching, most of the viewers are young; this may be the first time they’re seeing someone with a serious illness. It’s inevitable that many viewers end up internalizing the ups, downs, and losses, as if they knew these people in real life. “It may be the loss of someone they never met, but the loss is real,” Dehorty says.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Watching an imperfect life unfold online can be healthier than constantly comparing yourself to the staged, overly filtered posts that saturate social media. Witnessing the life, trials, and possible death of a person on YouTube can force followers to look beyond their own circumstances.

Despite the heavy subject matter, the relationship between these vloggers and their viewers is overwhelmingly positive. In fact, for some it’s connected them to friendships and experiences that have made the inauspicious situations almost worth it. “YouTube is like a little family,” says Alkobey, who went into remission 18 months ago, is getting married this year, and met all of her bridesmaids-to-be through social media. Dalton, too, found her best friend, an 18-year-old cystic fibrosis patient who lives across the country, thanks to YouTube. And many of Talia Castellano’s closest online pals are still in touch with her family, who created a childhood cancer foundation called Talia’s Legacy in her memory. This has been healing for them. “We've watched her fans grow up online, and they continue to tell us how much they miss Talia, how much she changed their lives,” says Mattia. “They come to Florida to visit us; they go to Talia’s Legacy events. We’re so grateful to have those people in our lives.”

In a way, YouTube has allowed people like Castellano to cheat death. At any time, her family and followers can go back and watch her hundreds of videos as if she were still here, dotting her eyelids with fluorescent teal shadow and flashing an ear-to-ear smile. It’s something Jeha has thought about a lot recently. “I've got a large family, and these videos are something I can leave behind,” she says. “They can watch them and see I was happy. I was laughing. I was alive.”

“They can watch my videos and see I was happy. I was laughing. I was alive.”

In an ideal world, these women make full recoveries and can refocus their channels on stories of survival. Thankfully, Alkobey was blessed with a positive outcome, as was Mary Dalton, who is now a cancer-free high school senior. She intends to pursue a career in film production. “YouTube totally changed my perspective on what I want to do when I get older,” she says.

Vloggers like Sophia Gall and Claire Wineland aren’t as lucky—they know they won’t survive their illnesses. But considering the circumstances, they’re thriving, and their channels have something to do with that. Gall continues to make inspiring videos for thousands of fans, hoping one day her content will produce enough money (either through ad revenue, or perhaps a line of merchandise inspired by her channel) to give back to childhood cancer research. Wineland, too, has big plans to keep making videos on her new channel and growing her foundation.

“When you really understand that you can lose everything, it makes you want to live—to create something,” Wineland says. “It makes you want to be a part of the world. I mean, why not do something big with your life while you still have it?”

Editor's Note: After publication, MarieClaire.com learned that Raigda Jeha has passed away. Our sincere condolences go out to her friends and family.

To learn more about Claire's Place or Talia's Legacy, or to make a donation, click here or here.