Against All Odds: My Journey from Nothing to Something in America

A future beyond poverty seemed impossible. Until I saw a way out.

The expectations for my life were carved out before I could have ever begun to imagine what I might want for myself. I suppose this is true for all children, including those born into privilege.

As a brown-skinned girl born to a teenage mother, I had a low bar of success. No one in my family had finished high school, and because we were poor, I did not expect much more than what I had, which was very little. It was assumed that I would become a domestic worker or maid in one of the mega-hotels in Las Vegas like my grandmother, a school-bus driver like my mother, a hairdresser, or a certified nursing assistant. And while these were all considered "good" jobs in my neighborhood and by my family, it is safe to say that none of them would lead to a solid middle-class existence with a comfortable retirement package and enough to pay for college tuition for my children.

The author as a baby

Growing up, I never believed we were poor. We had systems and networks that worked. If the electricity got turned off for nonpayment, we went to a neighbor's house or burned candles until it was turned back on. If we ran out of milk or money, we borrowed a couple of bucks from a relative or friend. We lived with little regard for what others had that we did not. There were no rich people in our lives to show us the deep divide or to make us wish for more. As a result, I did not resent my lack or understand the depths of my deprivation because I had nothing to measure it against. I lived in a cocoon of familiarity and geographic isolation, segregated by invisible but known boundaries that I knew never to cross. There was also no road map to a life or destination other than where I lived at any given time.

After I was born, we moved into a tiny one-bedroom duplex in Compton, California, that cost $100 per month. At night, the apartment complex would come alive with music and the sound of dice hitting the concrete walkway. Young boys crouched in tight circles, clutching dollar bills, yelling at the dice to come up right. A halo of marijuana smoke hung above their ring of Afros. Cans of Schlitz malt liquor and bottles of Thunderbird were lined up neatly just outside the circle, waiting for a fumbling hand to reach back for a swig. After a long day's work, my father would join the group to blow off some steam before dinner.

Author in second grade.

My mother did her best to shield my younger brother and me from the things that would make us question her, our circumstances, or our lives. She never talked about politics, race, or what was going on outside our neighborhood. She convinced us that our world was right and that the things we did not understand were of no consequence.

Our cupboards were bare. The most I could find was a stale box of taco shells on the back shelf and a lone bottle of ketchup in the refrigerator. At the start of the month, the refrigerator and shelves overflowed with milk, cereal, chicken, grits, Oreo cookies, and fresh fruit. However, by the end of the month, we ate rice and butter at nearly every meal and drank sugar water. My mother had long since quit her job at a convalescent home changing bedpans, washing laundry, mopping floors, and serving food because the next-door neighbor could no longer take care of my brother. After she and my father split, her main source of income was "The County," as she called public assistance. We survived on the once-monthly checks that arrived in the mail and on food stamps. I learned that accepting the checks meant that we were open to scrutiny by the state and social workers. On occasion, they would conduct a welfare check to make sure my mother was telling the truth about her circumstances. They were suspicious and scribbled notes on their writing pads as they walked through surveying our house and belongings. Did the television belong to us? Was that our car in the driveway? What was in the refrigerator? I believed they were trained to see us as criminals, not worthy of help or support.

Somewhere between the local community center and my elementary school, I figured out that I was bright and that school could be one of the few things in my life that I could control. It was a place away from the chaos, both physically and mentally, where I could create myself anew. When I parachuted into a new school, I would do my best not only to catch up to the lesson, but to exceed it with bonus assignments. My teachers, seeing my eagerness, created independent-learning circles away from the others so that I could continue to excel without distraction.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

When my mother met her boyfriend, our lives changed dramatically, seemingly overnight. I now resided in the local drug house. There were men moving freely throughout our house, refilling their stock to sell on the streets. There was also a safe filled with thousands of dollars of cash, marijuana, and cocaine stashed in my mother's bedroom. My brother and I stayed out of our mother's line of sight, and that is how she preferred it. We were raising ourselves, emotionally and intellectually, figuring out our places in the world on our own.

"I did not know there were real kids, not just those on TV, who had more and were being prepped for success. In all fairness, they did not know about me, either."

All of the schools that I attended from elementary through high school were average at best and failing at worst. However, growing up, I naively believed I was receiving the same quality education as other students across the country and that I had an equal shot at success. I did not know that elsewhere, students attended prep and private schools meant to funnel them to the most elite colleges and institutions. When I realized the truth, I was angry and felt like I had been cheated. The idea that I was excelling was suddenly placed within the context of the conditions in which I, and those surrounding me, had grown up. In the real world, I was behind, and the gap between my middle-class and upper-middle-class peers and me—between what they knew and what I knew—seemed insurmountable.

To be sure, at the time, there was nothing around me or that I could see to signal directly that the road ahead would be hard and filled with land mines meant to derail my friends or me. I did not know there were real kids, not just those on TV, who had more and were being prepped for success. In all fairness, they did not know about me, either.

By 11th grade, I had joined every club I could at San Bernardino High, my latest school. I was a varsity cheerleader, copresident of the Black Student Union, a member of the Future Black Leaders of America, and a member of our Mock Trial team, an organization for aspiring lawyers. I was enrolled in the Phoenix Honors program and took Spanish and French. I also had a trigonometry class that began one full hour before school started.

With a friend freshman year of college, 1995

Then, I did not make the connection between the way I dressed and the neighborhood I came from and the assumptions my teachers and others made about my intelligence and capabilities. I looked like everyone else in my neighborhood. I did not see anything wrong with my hairstyle, Air Jordan sneakers, or baggy polo shirt. However, the way I dressed was all my teachers and fellow students needed to see before turning me away or, in subtle but sure ways, letting me know I did not belong. I began wearing more formfitting clothes and dresses. I stopped wearing large, dangling earrings. I took my cues from the white girls in my class who shopped at the Gap, Wet Seal, and Charlotte Russe. It was all I could do to make sense of all of the things in my life I did not understand.

With her grandmother, 2014

Blythe Anderson was my guidance counselor. I checked in with her often to make sure I was on track for graduation. She thought I should explore the University of California, Berkeley, or another of the University of California schools because of in-state tuition, which was cheaper than going out of state. Before these conversations, I had never given much thought to what college I might attend, what I might study, or how I would pay for it. I also had no idea about entrance exams, the application process, or how to choose one school over another. Save for geographic location, I assumed all of the colleges were the same. I did not know the difference between an Ivy League institution and a state college. In this instance, information was currency. What I did not know could cost me dearly.

My mother and I hadn't been getting along for months, and following a brutal confrontation, I moved to my paternal grandmother's three-bedroom house in Las Vegas to finish high school. Including me, there were three adults and 10 children living there. On occasion, my cousins and I slept on an old, sunken-in couch on the front porch. At the start of each month, my grandmother and aunt combined the little money they had left after paying the rent and utilities to grocery-shop for the entire house. To get the most for the least amount of money, they shopped at the local discount grocery store in our neighborhood, where the meat always smelled and the vegetables were overly ripe. On more than one occasion, the household fell ill because the rotten meat we had consumed had been marked good for sale.

"They had a different way of being in the world, entitled and less fearful. I, too, wanted to feel like I owned the world."

I got a job scooping, cooking, and serving food to the thousands of tourists at the Riviera Hotel and Casino. I worked 40 hours per week and sometimes picked up a shift when someone called in sick. In every way, I was responsible for myself. And I took my job as seriously as I did school. Work provided me with the money I needed to take care of myself and to send money back home to my family. School is what I hung my future on. It was going to be my ticket out. My situation felt precarious, as if it could unravel at any moment if I were not careful. On school days, instead of doing homework or hanging out with my friends when I arrived home, I had just enough time to put on my uniform and catch the bus to the casino for work.

I was learning how to navigate my two worlds seamlessly. I could be tough when I needed to be—scrappy and resourceful. I hung out with my cousins at home and with the other black kids in the cafeteria during lunch. Simultaneously, and beyond the watchful eyes of my friends and family, I was meticulously learning the rules of how to succeed outside my neighborhood by observing the white kids in my classes. They had a different way of being in the world, entitled and less fearful. I, too, wanted to feel like I owned the world.

College was the topic of discussion in all of my classes. Everyone was applying, retaking the SAT, and talking about where they hoped to go. They spoke with such authority and certainty. With the exception of my vague conversation with Ms. Anderson about UC Berkeley, I had nothing to contribute. I tried attending a local college fair, taking off work and catching several buses to get there. When I arrived, I was overwhelmed. I did not know how to sort through all of the information on the tables or what criteria I should be using to decide which schools would be a good fit for me. The school representatives, while eager to help, grew annoyed with my lack of understanding of the process and my seemingly rudimentary questions. I did not know what a major was. I was unfamiliar with the financial aid and application deadlines. I needed more guidance, some help. I reached out to Ms. Bowman, who ran Future Black Leaders of America at my old high school, and she told me to apply to Howard.

I spent weeks working on my application. I included a table of contents, my transcripts, the typed blue-and-white long-form application, a few of my favorite poems and a short story that I had written, a personal statement, and whatever else I thought would help my case, then shipped the small binder off to Washington, D.C.

A couple of months after sending in my application, my grandmother waved a white envelope in the air. "You got in, baby, you got in! I couldn't help it. I had to open it."

I unfolded the letter and began to read, my eyes dissecting each line for confirmation of what had just been said. I examined the dark-blue imprint: Howard University. I had been accepted.

Editor's note: Mason received a full-merit scholarship to Howard University and earned her Ph.D. at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is currently the executive director of the Center for Research and Policy in the Public Interest at The New York Women's Foundation.

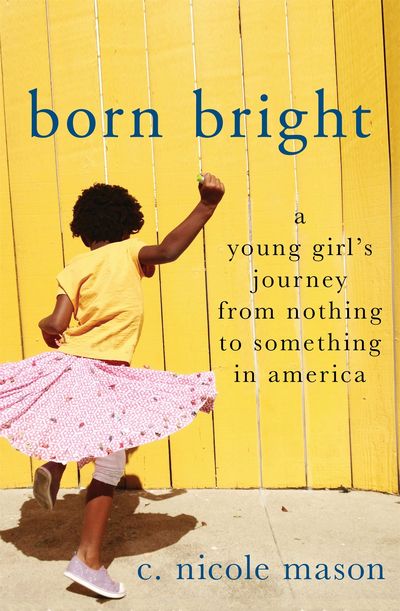

Adapted from Born Bright: A Young Girl's Journey From Nothing to Something in America by C. Nicole Mason, to be published by St. Martin's Press on August 16, 2016. This excerpt appears in the July issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.