Project Pearl: The Bravest Class in Town

Will a dogged group of college students in D.C. solve the grisly murder of journalist Danny Pearl before the FBI does? Interview by Abigail Pesta

Jessica Rettig, a 20-year-old journalism student wearing a bright blue cotton sundress and flip-flops, is sitting in her professor's office at Georgetown University, dialing a number in Pakistan. She's hoping to interview a man with possible ties to terrorists.

The man answers the phone and says he'd be glad to talk, but asks: Could they do it by e-mail instead? Rettig takes down his e-mail address, hangs up the phone, and sends him a quick note. Almost immediately it bounces back: address unknown. The e-mail is a fake.

It's a hard lesson — one of many — in what might be the toughest class in town.

Rettig and 20 other students are trying to track down the killers of Danny Pearl, the Wall Street Journal reporter who was kidnapped and beheaded by Islamic radicals in Pakistan in early 2002, a few months after the 9/11 attacks. The murder — which was the subject of the 2007 movie A Mighty Heart, starring Angelina Jolie — shocked the world and marked a new era of peril for reporters. The images of Pearl, a handsome, 38-year-old father-to-be, with a gun pointed at his head set the precedent for the sort of brazen kidnappings that have since become common in Iraq.

Leading the class is Asra Nomani, a journalist and activist who teaches alongside associate dean Barbara Feinman Todd. Nomani wants to finish the work the FBI started. "The FBI says this is an open investigation, but in talking to officials, it's clear there's no work being done on the ground," she says. "You can argue over whether it's right or wrong, but the FBI has moved on to other priorities." (The FBI says it can't comment on the status of the case.)

Called the Pearl Project, the investigation, now entering its second year, draws mostly female students from as far away as Qatar and Lebanon. Says Erin Delmore, a 21-year-old from New Jersey, "We're not studying history in this class; we're trying to make history."

And maybe they will. So far, the students have figured out the real identities of 15 of the estimated 19 suspects still at large, many of whom were previously known only by aliases. The next task is determining their whereabouts.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

For Nomani, there are deeply personal motivations behind the project. She was a close friend of Pearl's; the two worked together for nearly a decade at the Journal. "Danny and I were always scheming to get unconventional stories into the paper," she says, while sitting in her office amid maps of Pakistan, a basket of plastic dinosaurs, and a DustBuster. "He believed in breaking the mold." Indeed, Pearl made a name for himself by writing quirky front-page features about things like the world's largest Persian rug.

Nomani, now 43, bonded with Pearl over their backgrounds. "We were both children of immigrants. His parents moved here from Israel; mine came from India," she says. "He was Jewish, and I'm Muslim, so our stories are different, but still, he helped me find my identity. He helped me understand that I could be an American and a Muslim. When I told him I'd never been to a prom because I was a good Muslim girl, he threw me a prom and invited all our friends," she laughs. "I wore a ridiculous bridesmaid dress."

Nomani has an unusual résumé: A former travel reporter for the Journal, she has also written a book about tantric sex, in addition to a memoir about her pilgrimage to Mecca, Islam's most sacred city, as an unmarried Muslim mom. The New York Times has compared her to Rosa Parks for her gutsy brand of feminism. For inspiration, she carries around Nancy Drew's Guide to Life in her backpack.

"You don't have to be defined by boundaries," says Nomani, who received death threats when her controversial book about Mecca hit shelves. "I've learned that I can't compromise my voice. I can't be submissive. I have to be fierce."

Nomani traveled to India in 2000 to write her sex book, Tantrika, riding a motorcycle through the Himalayas to interview swamis, gurus, and scholars. After 9/11, she was reporting on news from Pakistan when Pearl was kidnapped. In fact, Pearl and his pregnant wife, Mariane, had been staying at Nomani's rented house in Pakistan when he vanished.

Nomani's home then became command central for the investigation. She and Mariane holed up there with FBI officials, Pakistani intelligence officers, and Journal reporters, poring over e-mails and phone numbers stored on Pearl's laptop to try to figure out who had kidnapped him. About five weeks later, a courier delivered a gruesome video of Pearl's murder to authorities.

Since that time, only four men have been convicted in Pakistan. Another man, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, an al Qaeda terrorist who is in U.S. custody for masterminding the 9/11 attacks, has claimed he personally killed Pearl, and Nomani's class is looking into whether he's telling the truth or trying to thwart investigators. Mohammed's claim has also been questioned by human-rights advocates, who suggest it could have been an attempt to alleviate harsh interrogations while in custody.

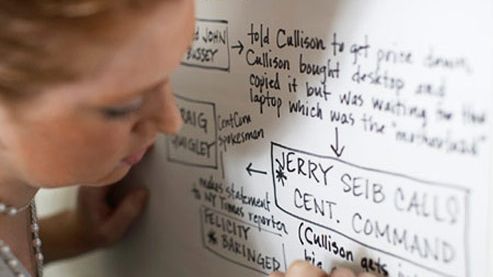

On a sunny afternoon, in a classroom plastered with handwritten charts of sources and suspects, Mary Cirincione, 22, stands up and summarizes her reporting on the infamous "shoe bomber" Richard Reid, whom Pearl had been investigating before the kidnapping. A couple of students lie on the floor; others lounge around on tables or chairs, listening intently. A stack of white three-ring binders labeled with names like "Asif" and "Zafar" sits near the door. Cirincione says she thinks she has found the e-mail address of a key Pakistani associate of Reid's.

After Cirincione's presentation, Nomani, wearing an Indian tunic and her signature pink Timberland boots, starts clapping. Then she smiles and says wryly, "I bet the FBI guys do that after their meetings — applaud everyone." The class breaks into laughter.

Typical course work goes something like this: To locate a man who may have guarded Pearl in the kidnappers' hideout, the students started Googling a name Nomani had obtained from a Pakistani policeman, trying to determine if the name was an alias. Progress: They found several newspaper stories about someone by this name who had been reported missing by his family. Then they contacted a lawyer mentioned in one of the articles; the lawyer, in turn, put them in touch with the family. Turns out the man in question is in jail on weapons charges. The class is now trying to contact him in prison.

A few of the students have only a foggy memory of the murder they are investigating, since they were just 13 years old or so when it happened. Others remember it vividly. Clara Zabludowsky, 20, recalls her high-school friends watching the murder video on the Internet after terrorists circulated it. "I couldn't look at it myself," she says. Shilpika Das, 26, a graduate student from India, watched the video and felt "horrified."

Nomani watched it herself with one of her graduate students, 27-year-old Kira Zalan. "I felt it was necessary in order to understand the forensic evidence the FBI has," says Nomani. "It's the ugly truth. To run from it seemed like doing our mission a disservice."

Among the students' many successes: They have managed to get their hands on the full-length version of the video — not the edited version that the terrorists released. (Nomani and Zalan got it from a source who can't be named for security reasons; the FBI has a copy as well.) On the longer video, the hands and feet of the killers are visible, along with other details that might eventually help to identify them.

Some of the students' parents worry about the grisly nature of what their kids are researching. Rettig says her folks "weren't thrilled" when she chased down the brother of the courier who had delivered the murder video to officials back in 2002. Rettig knocked on the man's door in Florida, then talked to him inside his home. Her younger brother was outside in the car. "He's a big guy," she says, "so I figured I could call on him if I needed him."

The students support each other as well. All praise the class's diversity, noting that the foreign students give the American ones a fresh perspective on the world. "We're not all from democracies," says Haya Al-Noaimi, 18, who is from Qatar, "so we don't necessarily expect a system of checks and balances. We know that in some places, a police chief can do whatever he wants."

Nomani hopes to kick-start a network of these types of courses across the country aimed at investigating journalists' murders. But for now, she is focused on the job at hand.

"This class is about the spirit of Danny," she says. "I learned a lot from him, and I always felt like Danny had my back. Now I have his."

Dedicated to women of power, purpose, and style, Marie Claire is committed to celebrating the richness and scope of women's lives. Reaching millions of women every month, Marie Claire is an internationally recognized destination for celebrity news, fashion trends, beauty recommendations, and renowned investigative packages.