Will the Real Taylor Swift Please Stand Up?

On social media, celebrity lookalikes are garnering fans and fame. But when you’re constantly being mistaken for someone else, it can change how even you see yourself.

While scrolling through social media in bed one evening, I came across a post of a somber-looking Taylor Swift from the 1989 era. All cat eyes and red lips; signature blonde bob dusting her chin. In the background, a stripped-down version of the song “Maroon” from Swift’s Midnights album played, as she stared in the mirror and began to take off her makeup.

Except, it was not Taylor. It was Ashley. One of the many Taylor Swift impersonators and lookalikes on SwiftTok—the portion of the app devoted to unpacking the singer’s lyrics, debating music video Easter eggs, and posting lookalike content.

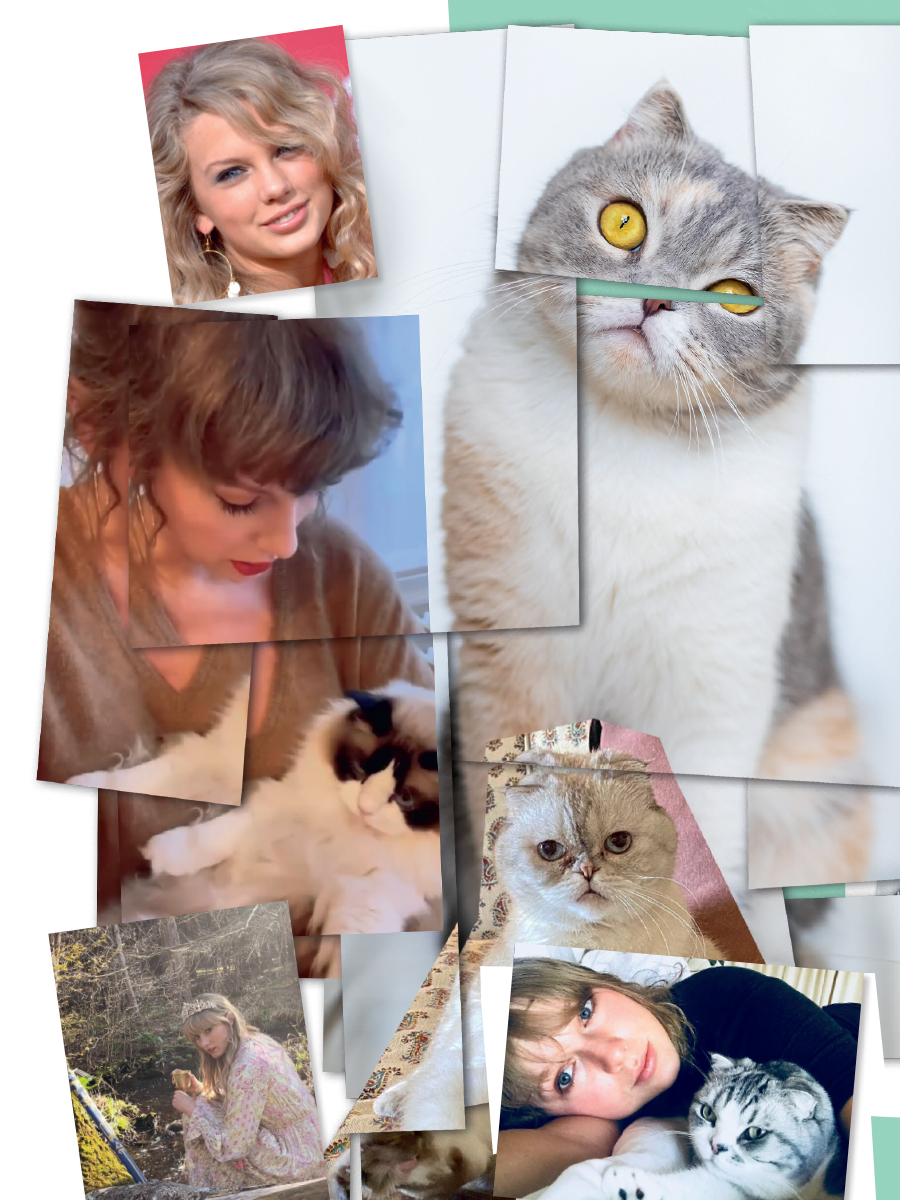

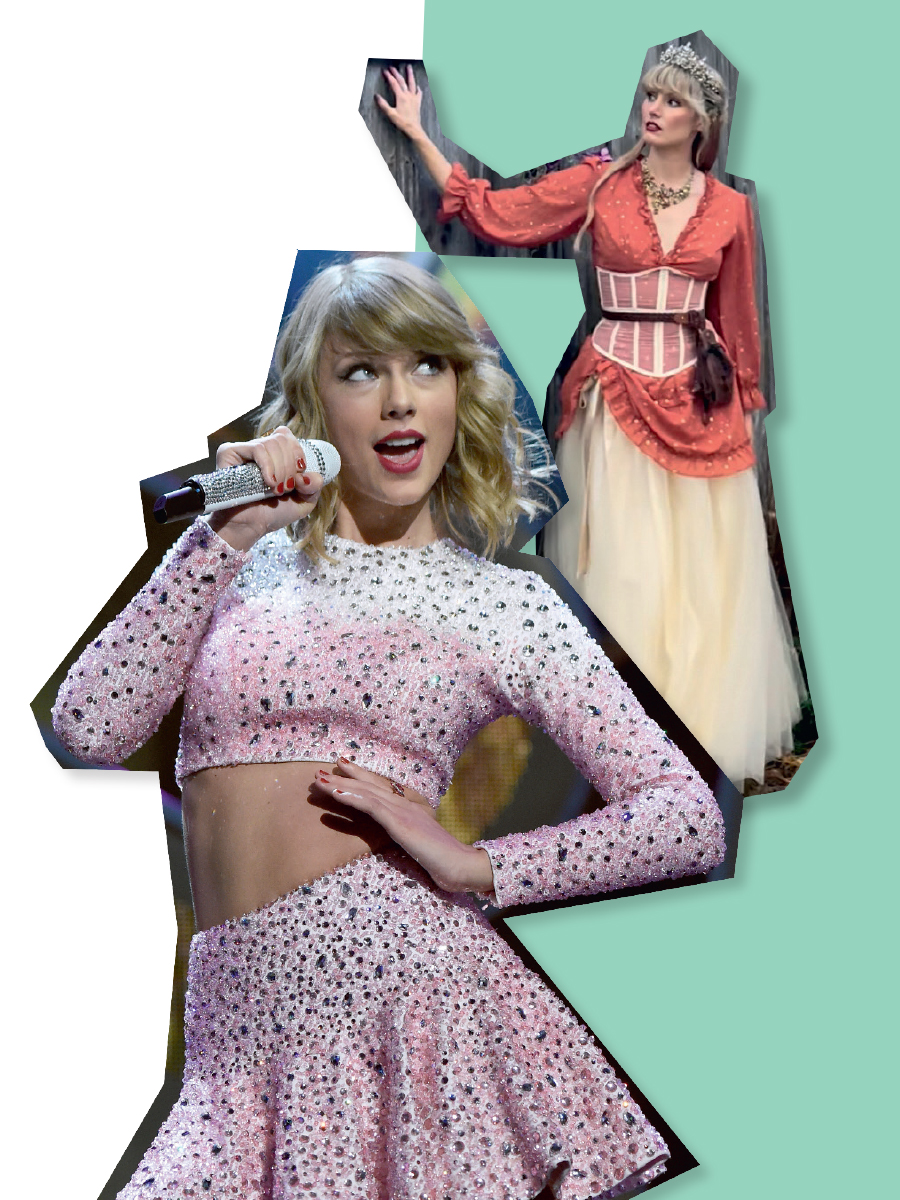

Of course, there’s Ashley (@noitisashley13—did you catch the Swiftie inside joke?), who is arguably the most popular. The 29-year-old married mother of two has more than one million followers on TikTok—and adorable cats that look just like Swift’s. The resemblance to the superstar is so uncanny, Swift’s own mother has commented on their similarities. There’s also Julie (@juliiieanne), a 24-year-old who lip-syncs Swift’s songs to her 305K followers while wearing ornate, sparkling, incredibly accurate costumes to the ones Swift has worn on tour. There’s the tattoo artist who designs Swift-related body art and the up-and-coming singer-songwriter who covers Swift’s music, and so many more. And it’s not just that they look like a celebrity—it’s that they’re able to earn money, certain levels of fame, and opportunities through leaning into that likeness.

The online impersonator economy is not unique to Swift superfans, either. There are Ariana Grandes and Dove Camerons and Adam Drivers. Kim Kardashians (et al.), Kate Middletons, and Christina Aguileras. As I continued to watch Ashley’s video, it wasn’t just her wow resemblance to Taylor that caught my eye, but a block of text that appeared on the screen: “How do you not lose yourself when everyone is constantly comparing you to a celebrity?”

Impersonators are as old as the concept of celebrity itself. Just look at all the Vegas Elvis Presleys. But it’s reached new heights thanks to technology, says Joshua Gamson, Ph.D., a sociologist at the University of San Francisco who has long studied celebrity and fandom in contemporary culture. Unlike the “fan clubs” of the 1960s, where even the most rabid groupies were, at most, attending concerts and writing letters, social media enables today’s fans to engage in ever-present ways. That ups the ante—and audience—for celebrity doppelgängers, who are often superfans themselves.

“Social media makes it particularly easy for ‘fan’ to become someone’s identity and then probably their central identity,” says Katy Coduto, Ph.D., an assistant professor of media science at Boston University who specializes in social media and interpersonal connection. “There’s a concept in my area referred to as ‘identity shift,’ where what you post online starts to become your ‘real’ self.”

The idea is that the more we present ourselves in a certain way online, the more we behave in line with that presentation privately and in real life. “As you’re posting online, you’re getting feedback,” says Coduto. “You’re getting likes and comments. If we post things online, even if they aren’t a critical part of us, they become a critical part of us.”

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The identity-shift theory was coined in 2008, but it’s reminiscent of the famous Kurt Vonnegut quote from 1961: “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.”

By definition, identity shift is “the process of self-transformation resulting from intentional self-presentation in a mediated context,” according to a 2021 article in the Journal of Media Psychology, wherein the “mediated context” is now TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and dating profiles.

The more we present ourselves in a certain way online, the more behave in line with that in real life.

The authors state that “individuals feel more beholden to self-presentations that are visible to others,” especially when these are persistent, authentic, and validated by external feedback. Subsequent studies also found that “confirmatory feedback” from a person they know—or believe themselves to know—“evoked greater transformation,” as did committed and persistent messages targeted to a narrow or deliberate audience.

Of course, there are limits and caveats for how this process works. You cannot, for example, “identity shift yourself to believe you are an asparagus stalk,” as the study noted.

But Kylie Jenner? People might believe that.

All of that said, it’s not just that constantly being recognized as a celebrity could change your relationship with your identity—though that’s possible—it’s more that being constantly misrecognized could “feel really encroaching on your own sense of identity,” says Sharrona Pearl, Ph.D., an associate professor of bioethics and history at Drexel University and a theorist on the face and body. “One might want to be really careful about that relationship.”

Sofia Divene (@sofiadivene_), a 25-year-old Los Angeles-based TikToker who has a striking resemblance to Christina Aguilera, believes she “went through an identity crisis” when she began to post as the pop star. Mainly because she was so young. “I was still figuring myself out, and when I started to go viral, there were a lot of mean things being said about me and a lot of assumptions about me, too. I got a lot of people asking, ‘Why can’t you just be yourself?’ It hit hard because I really didn’t know who I was.”

Now, she only posts as Aguilera sometimes. “I don’t want to be held to one niche where I live in someone else’s shadow,” she says. “Don’t get me wrong, I love recreating the looks, I love how happy it makes my following, and I have the utmost respect for Christina, but I want to be known and valued for being myself and my work.”

Of course, role playing is also just fun. Allegra “Pi” DuVal (@dearbritney), who started out tribute-performing and dancing live, has been able to market her Britney Spears impersonation material to a global audience through TikTok and Instagram. DuVal, 34, already looked like the star, but in her content she is truly performing, with full costuming and makeup. She makes her own outfits, bleaches her hair, hits the gym, and studies dance routines in order to make her shows stand out. Her lookalike work has taken her all over the country, where she performs as Spears.

“The best part is getting to pay tribute to an artist I have looked up to for years,” she says. “These people may never get to see her perform again—or at all—and seeing the joy Britney brings is so heartwarming.”

We're all kind of overly crazed fans of something. How do we decide what things are or are not okay?

DuVal knows she “might look similar to Britney and emulate her” to her nearly one million followers, but she still feels like her own person with her own life goals, interests, and tastes.

In some ways, it’s less about adopting someone else’s identity and more about finding a stronger connection to your own. “On some deep level, there’s a search for kinship,” says Pearl. “The only people who really look like each other are identical twins, and we have a biological narrative for that. So what if you could find someone else who looks like you?” And so, sometimes, the benefit of impersonating a celebrity means comments and likes from the artists themselves, money, and fame, but sometimes it means a feeling of community that they otherwise wouldn’t have tapped into.

And who’s to say what’s too much when it comes to how we choose to present ourselves? “We have a history of accusing people who are ‘too’ interested in pop culture or light things as having no identity,” says Elena Maris, Ph.D., an assistant professor of communication at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on media technology and pop culture. “We’re all kind of overly crazed fans of something. But how do we decide what things are or are not okay? To paint yourself blue for a sports team isn’t often seen as ‘crazy.’ What about being a Trekkie and wearing your costume to your con?”

June (@Junipers_Castle ), a 36-year-old TikTok creator based in New England, dabbled in professional work as a Taylor Swift impersonator, attending events for lookalikes, impersonators, and tribute artists. She says she was even scouted for a network TV show. In public, she’s been mistaken for Swift several times, including times where the fan was tearful or shaking. Last year, Swift herself liked one of June’s TikToks.

At her followers’ request, she would post images of herself in certain outfits or makeup looks Taylor had worn. But it eventually “got to be too much,” says June. “If you even remotely resemble a popular celebrity and play into it, people will try and bring you down. Sometimes it’s jealousy, sometimes a hyper-protective fandom, sometimes another lookalike on a burner account trying to make you feel insecure because they see you as competition, which is ridiculous.”

According to Maris, music fans in particular tend to be really protective. There are thousands of people for whom “Taylor Swift Fan” is their identity. And as Coduto points out: “They are so passionate that they feel like they know her and have a parasocial relationship with her.” And that can heighten a sense of responsibility that they feel to defend the star.

DuVal occasionally gets a different critique from some Britney Spears fans—in particular when the star herself is struggling: that her impersonation videos aren’t ethical. Which does raise the question: when does an impersonator become an imposter? How much of a person’s identity is okay to replicate before it becomes more than just borrowing it?

As June explains it, “I always tell people that I’ll take a photo so long as they know I am not Taylor, nor am I claiming to be. I’m always flattered people mistake us or see a resemblance, but I never want it to come across like I’m actively trying to run around fooling people or claiming to be someone I’m not. I have way too much respect for Taylor than to do that.”

But online, June is no longer obliging. She’s transitioned to a new TikTok where she focuses on fantasy content. “I think a balanced and full life outside of a career or side hustle, regardless of what it is, is so important,” she says, adding that it’s necessary to have a “mindful perspective of what it means to share your life online, lookalike or otherwise.”

And that’s the thing. These impersonators are “just dealing on a larger scale with the question of identity that we’re all dealing with,” says Maris. The struggle of how to present ourselves on dating apps or Instagram or Twitter. Or anywhere. Navigating that can be complicated, even without the extra layer of having a famous doppelgänger. Although, when it comes to doing that successfully, maybe we should embrace the words of Taylor Swift (the real one) herself: “You’re the only one of you. Baby, that’s the fun of you.”

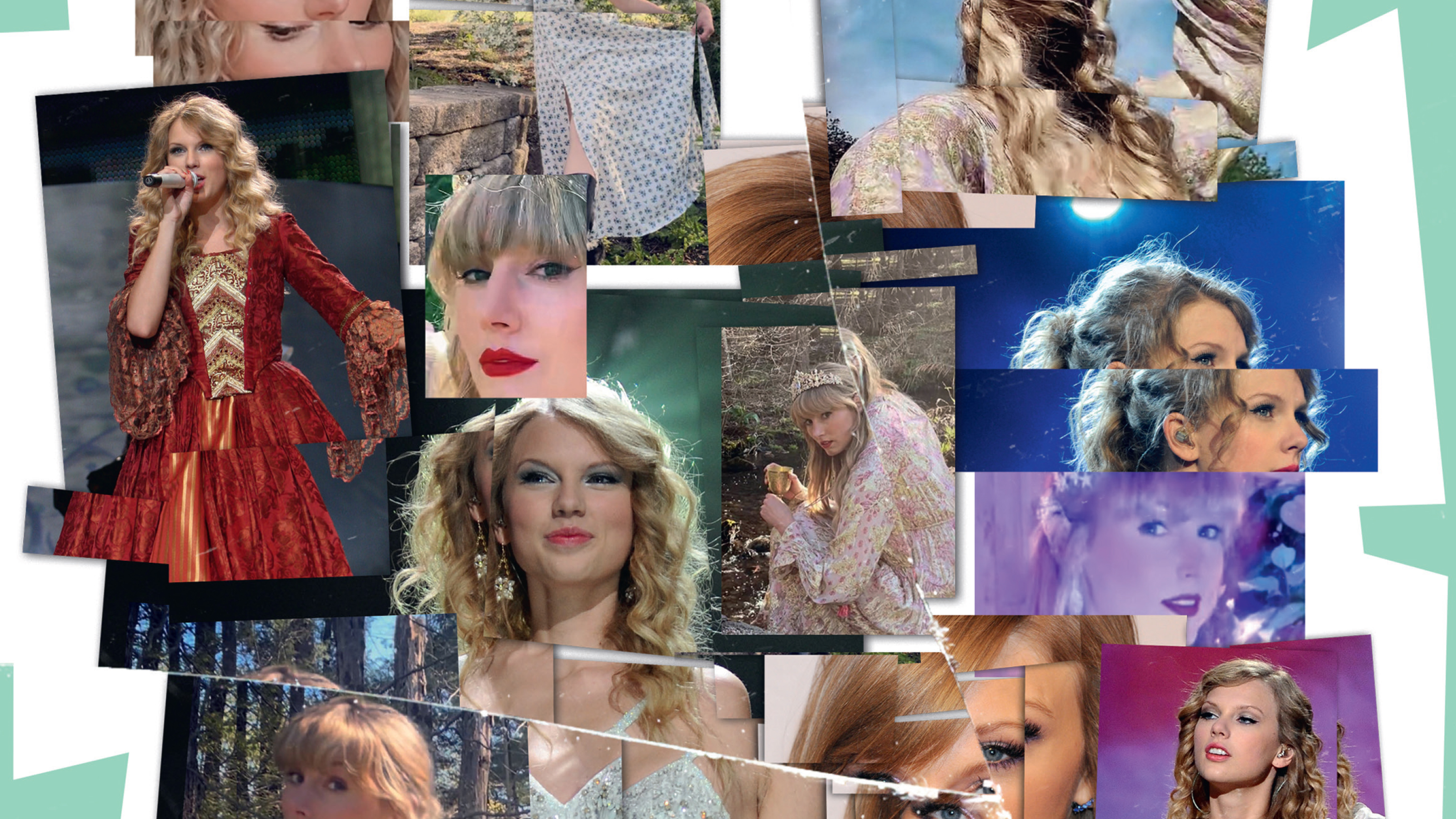

Did you guess correctly? The photos marked with a red dot show the pop star (and her cats!). The others are all @junipers_castle.

Olivia Messer the former lead COVID-19 reporter for The Daily Beast. Throughout her journalism career, she has completed groundbreaking investigative reports on subjects ranging from crime and education to politics. She has also written first-person essays on what it means to witness a murder or to experience sexual-assault, and she was the first reporter to name the identity of the Golden State Killer. She has worked as a local crime reporter for the The Waco Tribune-Herald, fact-checked at a travel magazine and done freelance political reporting for The Texas Observer. She graduated from McGill University in Montreal.