How I Came to Love My Body—a Decade After My Eating Disorder

Caroline Rothstein suffered her whole life. Then she chose to recover.

I started thinking I was fat when I was 4 years old. The actual size of my body doesn’t matter; I had internalized cultural and global messaging that dictated how people—especially self-identified girls—were supposed to look and think. In elementary school, I experienced antagonistic body shaming and bullying from classmates, peers, my ballet teacher, medical professionals, even friends. The loudest voice, though, was always the one inside my head.

My eating disorder began in sixth grade. My family was on winter vacation in Japan. My father and I went to the gym. Treadmills lined an Olympic-sized swimming pool with the Tokyo night sky peering in through the glass ceiling. I was in a T-shirt and shorts, most likely Umbros, as it was December 1995. We jogged on adjacent machines for 20 minutes. Mid-run, I decided that when I got back to middle school, I was going to stop eating lunch. And so, I got back to middle school, and I stopped eating lunch.

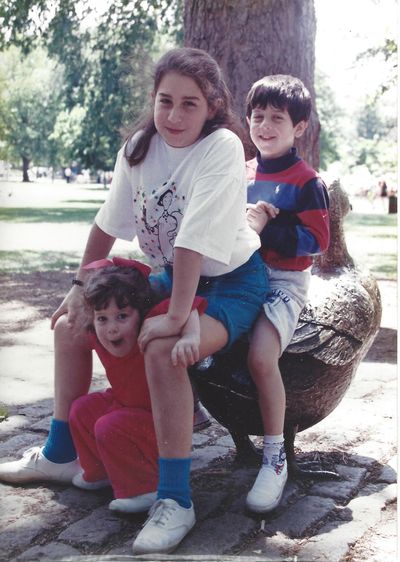

The author with her younger brother and sister at age 11.

While I can pinpoint the inception of my clinically diagnosable eating disorder, the roots of my illness were planted long before the behaviors took hold. I turned to starving myself (and later to binging and purging and other self-destructive behaviors) because I didn’t have access to resources or language that would enable me to better manage my anxiety and various experiences with trauma.

My eating disorder was not an exercise in vanity or a haphazard way, in a fat-phobic world, to simply lose weight. My eating disorder, like all eating disorders, was a mental illness. A mental illness that can be deadly; anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental disorder. Every 62 minutes, at least one person dies as a direct result of an eating disorder, according to the Eating Disorders Coalition for Research, Policy & Action. Research states an estimated 30 million Americans will suffer from an eating disorder in their lifetime. The disease does not discriminate. Sufferers span demographics—gender, age, sexuality, race, ethnicity, nationality, ability, class, and more.

Some studies say it’s about genetics. Other researchers look to environment, trauma, and co-morbidity, which refers to illnesses that many people struggle with alongside and directly impacting their eating disorder—like how I also suffered from depression and anxiety. It’s a term we overlook (a lot), and that inhibits our ability to understand the way eating disorders unfold.

My eating disorder, like all eating disorders, was a mental illness.

An eating disorder (or any mental illness) is not a choice. For me, recovering from an eating disorder was. It was and is an active, life-saving, opportunity in the wake of a deadly, uncontrollable, nefarious disease. I had access to recovery. I had access to this option. I know that this option is a privilege, a privilege I had as a white cisgender able-bodied woman from an upper class background in the United States. That is not a option everybody has. Easily or ever.

Like the eating disorder, the seeds for my recovery were planted for years before they took root: Inside and outside of therapy I was learning that I was allowed to love myself, realizing that my body was a gift, understanding the cathartic power of my work as a writer and performer. Then one night during my junior year of college, I realized I’d been killing myself for 10 years, and I stopped wanting to die. I sat on my bedroom floor with my best friend, grasping for life. “I think I’m dying,” I told her. “I keep getting closer to death.”

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

That night, I made a pact with myself: Purging is not an option; I chose to live.

The author canoeing in Maine, circa 2005.

I liken my recovery to moving into a new house. I started with the foundation, forms of clinicial and personal advocacy—therapy, medical treatments for various traumas, and a support system of loved ones. Then the walls, things that help me maintain my mental health—spoken word poetry, yoga, meditation, journaling, taking long walks. The roof, behavioral techniques I used to move forward—intuitive eating and honoring my body’s cravings and needs. The furnishings, art I leaned on in moments of crisis and joy—my favorite movies, music, and books. And then, when I was ready, I moved in.

On a recent Saturday afternoon, I was meditating alone in my bedroom. I was pants-less, and midway through the 10-minute timer I set, I felt an insatiable need to take off my shirt. So there I was on my black-and-purple meditation bean bag, wearing only a bra and underwear with a blanket covering my lap, and I noticed, as I kept my eyes closed and tried to focus on my mantra, that I loved my body. I felt beautiful. I felt sexy. I maybe even felt hot.

That moment by my bedside with my stomach rolls scrunching and my ass fat spilling out felt like a miracle.

This is important, even radical, not just because of the eating disorder that overtook me from ages 11 to 21; the cocktail of anorexia, bulimia, binge eating disorder, over-exercising, diet pill abuse, and more. But because I am a survivor of both rape and sexual abuse. My body has been—more than once—a crime scene. Throughout this time, I also struggled with depression, self-harm, and suicidal ideation. Now, at 34, I’ve been fully recovered from an eating disorder and self-harm for 13 years.

That moment by my bedside with my stomach rolls scrunching in on one another, my ass fat spilling out of my underwear, and my arm flab sticking to my torso like wings, felt particularly potent. It felt like a miracle. To be grateful of and for my body at that moment and at all—in the face of my own history, and myriad systems of oppression, and the billion dollar diet industry that works incredibly hard to make me hate myself—felt redemptive.

The author about three years ago in NYC.

Let me be clear: My experience is my unique experience. Each of our body’s journeys—in illness and in healing—are unequivocally individual. I was able to build a recovery house for myself because I had access to the support systems, finances, healthcare, and food that allowed me to heal in a way that worked best for my body and me.

We need to create a world where eating disorder and addiction recovery is an accessible option. That means better understanding how co-existing mental disorders can complicate someone’s ability to recover. That means insurance coverage, accessible care for trans and non-binary individuals, and the elimination of stigmas and myths around what an eating disorder is and who it affects. That means affordable therapy and mental health services, and a dismantling of the Diet-Industrial Complex. That means doing work rooted in racial and economic justice. And queer rights. And fat positivity. Because all of the body shaming and weight stigma—it is killing us.

Despite my privilege, my reproductive and body rights as a person with a vagina are repeatedly at risk. I am threatened with catcalls and harassment so often I stopped keeping count. The multi-billion–dollar diet industry is built on the tenet that I am not enough. And so, given my body’s personal history, and the societal expectations of my body, it feels like an act of resistance to choose to love my body. To call my body beautiful. To know my body is worthy. To honor my body as whole.

My ability to love my body, to feel sexy, and beautiful, and hot was a radical act of resistance.

So that Saturday, half naked in my Manhattan bedroom looking out my window into the slowly dimming sky, I knew my ability to love my body, to feel sexy, and beautiful, and hot—without relying on anyone else’s opinions or thoughts—was a choice, and a radical act of resistance.

That’s how I was able to choose recovery: I realized I was killing myself and I didn’t want to die. I shut out the voices inside my head and around me—the systemic ones violently spitting vitriol at the various identities I hold—and I used the many years of therapy and recovery training I had in my toolbox to resist the deadly disease inside my head controlling my body and my thoughts. May we create a global toolbox of resilience and access to healing and care so that everyone can resist this deadly disease. It is possible to end this epidemic.

If you or someone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, these organizations have trained support available by phone and online:

National Eating Disorder Association, 1-800-931-2237

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, 1-630-577-1330

MORE ON EATING DISORDER AWARENESS WEEK

Caroline Rothstein is a New York City-based internationally touring and award-winning writer, poet, performer, and educator. Her work has appeared in Marie Claire, Cosmopolitan, BuzzFeed, NYLON, Narratively, The Forward, and elsewhere. She has been featured widely including in The New Yorker, MTV News, Chicago Tribune, CBS Evening News, BuzzFeed News, Huffington Post, Mic, and Newsweek, and was called a “very inspiring woman” by Lady Gaga.