What It's Like to Undergo Chemotherapy During COVID-19

Michelle Hynek, 46, was diagnosed with stage four colorectal cancer seven months ago. For her, isolation looks a lot different.

Michelle Hynek is a 46-year-old production executive and mother of two living in Los Angeles, California. She was diagnosed with stage four colorectal cancer in October 2019. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States five months later, things became a lot more complicated for Hynek, who is immunocompromised and undergoes an aggressive chemotherapy schedule—now no longer allowed to have anybody by her side when she goes to the hospital for treatment. Here, Hynek shares how her life has been altered by COVID-19, and why, despite how life-threatening it is for her, she isn't afraid of the virus.

I was adjusting my necklace when I felt a couple of lumps on my shoulder. I had a few indications that something was wrong, but at the time I had a general practitioner who was pretty dismissive. At one point, he sent me to a shrink because I kept calling him and complaining about certain pains, which was a big lesson about trusting your instincts when the person in the lab coat isn't addressing what you're feeling in your body. I went through the ultrasounds, the MRIs, and the biopsies before I was finally diagnosed with stage four colorectal cancer in mid-October.

Originally, they couldn't even figure out what my primary [cancer location] was, they just said I had adenocarcinoma. I couldn't even spell it. I had to have a doctor spell it for me on the phone. My production skills came in very handy because I was relentless [about getting information and scheduling tests]. If I would have just gone off of what the doctors were saying, you know, "Oh, we'll see you next week; we'll do this the following..." I would have probably been one or two months behind where I currently am.

In mid-November, I started chemotherapy, and I just finished my 12th cycle. In the beginning, surgery was not possible, which was a big bummer. When you find out you have cancer, you think, Okay, they'll just take it out, but it wasn't a possibility for me. Luckily, my body has had such an amazing response [to the chemo] that in the beginning of the year, my current doctor took my case in front of a tumor board and he had me meet with three different surgeons. They all agreed that I was an option for surgery. That was a huge weight off my shoulders and my family was super hopeful. Unfortunately, my surgery was scheduled for April—in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.

I have a very aggressive chemo schedule. Every two weeks, I spend Monday in the hospital at the University of Southern California (USC), and then I leave the hospital with [a drug] called the 5-FU for two days. Before COVID, I would get to the hospital at 7 a.m. to get my blood drawn, see my doctor and the nurse, then get my chemo. Because I have so many side effects, they have to infuse it over a long period of time, so it's over eight hours.

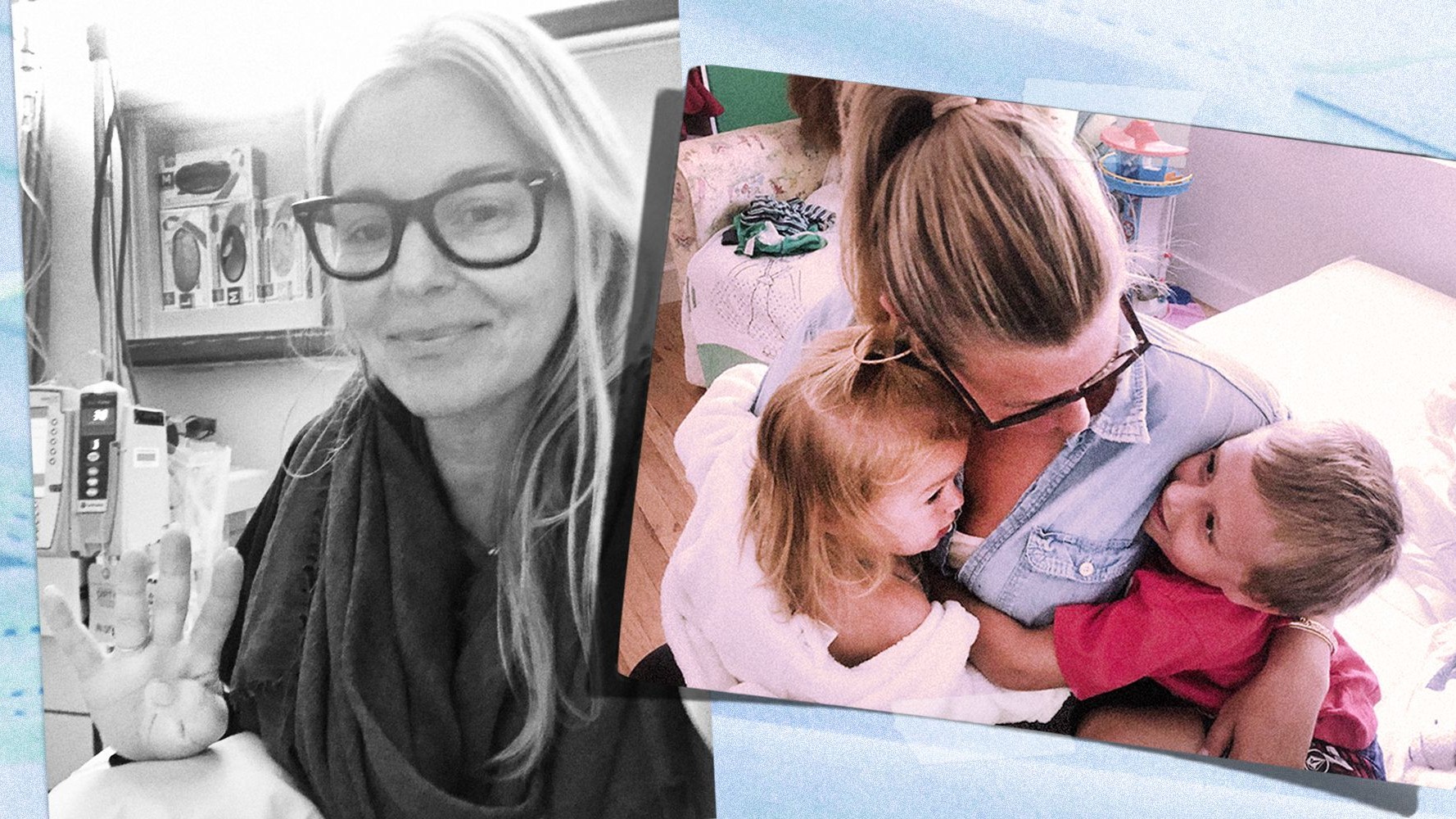

Michelle (left) and her friend Kelly (right) during Michelle’s chemotherapy session pre-COVID.

I have an amazing friend, Kelly, who had been coming with me to every single Monday chemo—all day. She was a big force in keeping my spirits up that whole time. All of the other people getting chemo... I didn't really see anybody doing much other than sleeping or staring into the abyss, which I've now come to do. But before, Kelly and I would talk. We'd talk about our friends and we'd FaceTime them. I would bring books, magazines, oils, and crystals. I had a rolling cart like you bring to the farmers market filled with pillows and blankets and extension cords and anything in the world that was going to make me happy and cozy at chemo. Honestly, those five months when I had her there with me, I never dreaded it. I didn't get sad on Sunday night before I was going. I was excited that we were going to have the day together. I wasn't afraid.

After that, I have two days of take-home chemo. It's a slow infusion over that Tuesday and Wednesday. My husband sleeps on the couch because the sweating is toxic, so I literally just stay in my bedroom alone for two days. I wake up and my mother or whomever is here will give me pills every three hours for the nausea and try to get me to eat or drink something, but I don't really eat or drink. I have a big window that looks out to our back garden, and I either sleep or stare out the window. If my kids are playing outside, they'll sometimes come up to the window, but they know that on those two days mommy's having her medicine and she needs to rest. I don't really like them to see me that way. I've never felt a freer moment than that Wednesday. I'll come out, and my bedroom door has pictures that [my kids] painted and drew taped to the door.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

It was a big lesson in life about trusting your instincts when the person in the lab coat isn't addressing what you're feeling in your body.

Because I get my treatment at USC, the hospital where COVID patients are treated is not the same building where cancer patients are treated. Nobody prepped me at all for anything COVID-related, which was kind of weird in the beginning. Now, when you go to the hospital, there's a line outside and they have these circles that they placed on the cement and on the floor inside to keep you six feet apart. When you walk in, there's a table and four nurses there. They check your temperature with the laser temperature, they make you change your mask to one of their surgical masks, and then they ask you a bunch of questions, like whether you've traveled and whether you've been in contact with anybody [who might have COVID]. It's kind of like going into a club: They check your name, make sure you have your reservation, and then I'm allowed to bring one person with me into my doctor's appointment—but not into the day hospital and into my blood draw, where Kelly stayed with me.

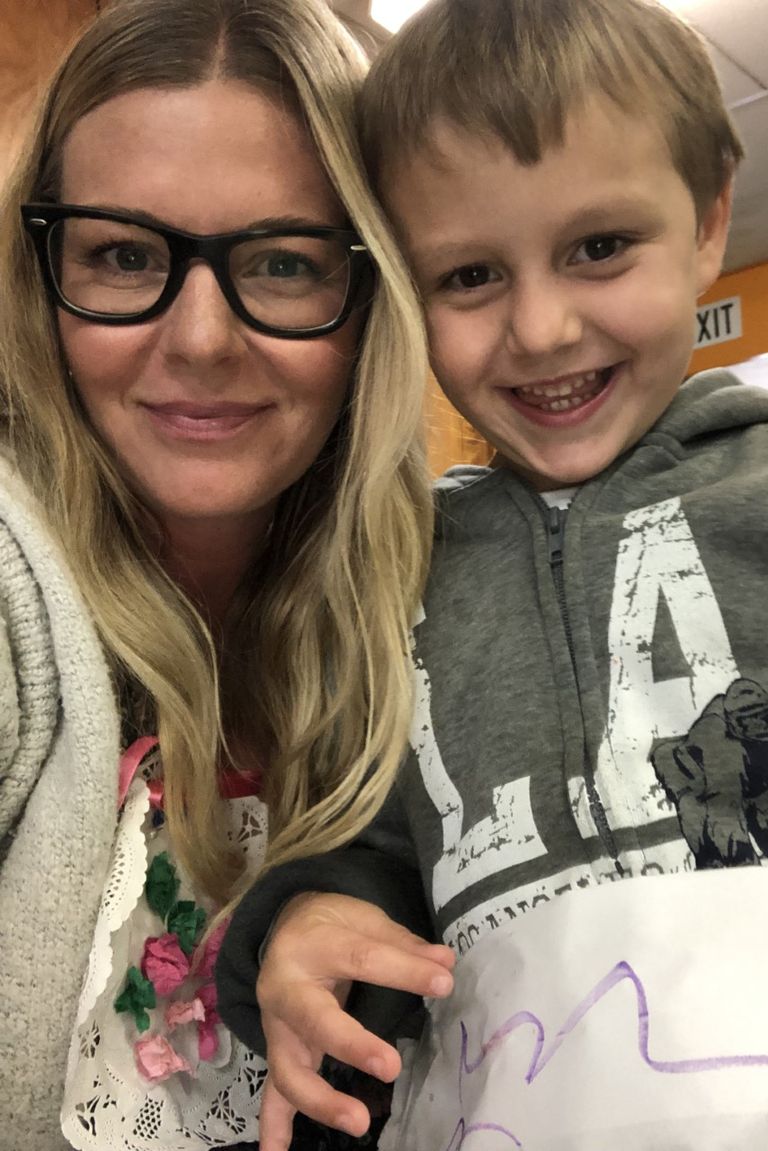

Michelle and her son, Billy, during a Mother’s Day party at his school in 2019, pre-cancer diagnosis.

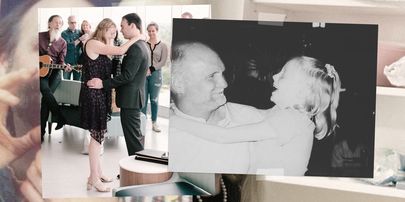

Michelle and her daughter, Stevie, at the beach last summer, pre-cancer diagnosis.

We used to have a family calendar, where my mom, stepmom, sister, niece, friends, aunts, cousins, etc. would pick a week to fly out and help me on the chemo week, take care of me, and take care of the kids. [My husband and I] needed to keep working as much as we could because cancer is not cheap. So that family member would also drive me [to the hospital] and take me home. Now my husband is out of work, so he will come in with me to see the doctor because sometimes you're getting news that you can't quite digest. He'll stay with me until I finish seeing the doctor, and then he leaves me. He picks me up at the end of the day, around six o'clock. I'm in a wheelchair on the curb. The nurse rolls me out to him and they do the handoff.

I didn't expect to see the kind of fear that I saw in my doctor's eyes when he had to break it to me that they were canceling my surgery. I had a pre-op procedure that was supposed to be done on March 20th, and the surgeon cancelled it the night before. I didn't think that COVID-19 was enough to be canceling things for cancer patients. This isn't elective, this is my life. I was crying to the nurse saying, "How could you do this?" The surgeon and oncologist didn't want me to be at USC because at that point there were around 25 COVID-19 patients and they didn't want me to risk being exposed. Another part of it was due to the location of my primary tumor. They thought the recuperation time would be longer. So they decided to postpone my surgery and put two more months of chemo ahead of me, saying we'll discuss it at a later point when it's safer for me to be in the hospital.

At first, I was very upset about it because I kept thinking that the surgery would save me, but the more I started realizing what it was going to look like being in the hospital alone, the more relief I felt that it was postponed. I see how isolating it is even when I'm there for one day with a bunch of nurses that have become like family to me. If I had the surgery, I would be in a strange hospital that has other priorities. So then I was happy to have it canceled, but I didn't really think that in the beginning. I kept thinking No, it's cancer. Of course, this is way more important than COVID. But it's not.

It's kind of like going into a club: They check your name, make sure you have your reservation.

My doctor would always wear a lab coat and be sharply dressed in a suit and tie. The first time I went to see him after [COVID-19] all started, he was completely covered in scrubs and a face mask. He will no longer do a physical examination on me weekly unless there's something wrong. He won't touch me unless I'm having an issue. And where everybody was allowed to bring one or two people to their chemo, now we have nobody. There would be volunteers who would ask if you wanted hot water, food, etc. Now, they don't allow any volunteers and patients don't have a caregiver with them. My friend Kelly and I would always order some kind of healthy takeout for us and the nurses, but I can't order Postmates because I can't go outside to go get it. So, most of the time I don't really eat anything. I barely drink any water because you get forgetful. Not having that person there to push you to keep going...it's depressing and isolating. I just let [the nurses] get me an Ativan so I sleep the whole time.

Before COVID-19 started, I was doing all of these things that people are doing now to keep germs out of their house. Since November, we've been implementing no shoes in the house. When the kids come in from the outside world whether it's school, the park, whatever, they have to take off all of their clothes and those go into the laundry right away and they have to wash their hands and their face. I wasn't going to malls, I wasn't doing a lot of grocery shopping—I would still go to the outdoor farmers market and to a few friends’ houses, but I was already limiting my contact with people. So for me and my family, luckily, there were a lot of things already in place. My kids were used to being hand-sanitized to death.

Michelle, her husband, and her kids enjoying a day at the pool in Palm Springs pre-COVID. "I was having so much pain in my hands and feet from the cold sensitivity, my friend sent us to his desert house so the heat could help my numbness. One of the best weekends we have had as a family since my diagnosis."

I haven't seen Kelly in two months. I see her on FaceTime and I drove by her house on her daughter's 13th birthday with my 2-year-old who sang happy birthday through her karaoke machine out the sunroof, but as far as spending every other week with her, it's been months and months. I was very fortunate to have had so much support from my friends, my family, and my coworkers. I've never felt so much support and presence in my life. Now it's a little difficult. You kind of feel locked back in a bubble and everybody's very afraid for me.

I wasn't afraid of COVID then, and I'm not afraid of it now.

Since March 9, other than going to chemotherapy and walking the hills behind my house, I haven't left. I don't go to the store. I don't go anywhere. My husband has taken us on a couple drives to the poppies and we found a dirt road where nobody was, but I haven't gotten out of the car. We all stay home. My 2-year-old doesn't have school, and my 5-year-old is in pre-school where they do a zoom call. My mom had flown here right before all the shutdowns happened because she was going to be here to help take care of me during my surgery in April, and she hasn't been able to leave. So she helps every day with the kids, keeping them alive and entertained. I've heard how boring life is a million times, but it's also been a really amazing, magical time for [my kids]. That has not been a huge challenge.

Michelle during her fourth chemo treatment.

My friends used to do "family dinner" on the Saturday after my chemo because I have a very hard time pushing back into eating and I can't really lose anymore weight. One of my girlfriends would have all of our friends over to her house, and she would make a super healthy meal because I'm on a sugar-free, dairy-free, gluten-free diet. But on that Wednesday [March 11] when I woke up, the world went crazy. COVID-19 had exploded by then. We had a dinner scheduled for the 14th and my birthday was on the 13th. But all of my friends decided we should cancel it and we shouldn't put me at risk. One of my friends was saying that she wasn't feeling well, and that she should definitely not come if we did do it. It turns out she and her husband had COVID.

I wasn't afraid of COVID then, and I'm not afraid of it now. It's very strange. I have a friend that I text with who's also a stage four cancer patient. I texted her [when the virus was declared a pandemic] and I was like, The world's gone mad. Everybody's so afraid. She said to me that she feels like the whole world feels the way she felt when she got cancer—all of the unknowns, the questions, the wondering if things are going to be okay or not, the wondering how much you're going to suffer. So many of the exact same things cancer patients feel when they get diagnosed.

Everybody kept worrying about COVID for me, but I'm more worried about my cancer. I already have cancer. I don't have COVID-19. I know how many precautions I already take to keep germs out of my life and my family. Being diagnosed with cancer, I have also learned a huge lesson on how to keep fear out of my mind and my body. I've had five months of therapy and help in getting that stress off my shoulders. So I haven't ever been afraid of COVID, but I do understand the fear. I understand that it would probably be life or death for me.

Most of my friends understand that spreading this further could kill somebody like me. But then other friends and family still aren't taking it seriously. I've been encouraging people to stay home. And I keep saying the more you don't stay home, the longer it's going to last and the worse it's going to be for people like me. I'm the person they're talking about when they speak about immunocompromised people. When the rest of the world opens up and they are going to beaches and going back to stores, I still can't go until there is a solid medicine that's going to cure this, or a vaccine. Life is still going to be looking very isolated for me.

If you'd like to contribute to Michelle's GoFundMe her friends set up to help pay for her medical expenses, you can do so here.

Related Stories

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.