Millions of Americans Have My "Invisible Disability." You’ve Probably Never Heard of It.

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) can make daily life a struggle. So why isn’t it better known?

When I was 9, my teacher took my parents aside and suggested that they take me to see a specialist. She couldn’t put her finger on it, but there was something “off” about me. At the time, we couldn’t have known that London, our hometown, was one of the few places in the world that might recognize symptoms like mine (clumsiness, disorganization) in the ’90s. I submitted to a battery of tests—could I copy the shape of a kite onto a fresh piece of paper? throw a ball against the wall and catch it?—and, days later, we had an answer: I have a classic case of dyspraxia, known in the U.S. as developmental coordination disorder, or DCD.

Some things, the specialist told us, would always be harder for me: walking, talking, tying my shoelaces. Finagling my way from point A to point B, both in terms of physical terrain and in my own head. I’d probably struggle with my speech, my handwriting, physical or mental sequences—anything that involved motor skills, a term that refers to the brain-body mechanism that allows you to wave, run, chew, or speak without even thinking about it.

The phrase “motor disability” went right over my 9-year-old head, so the specialist explained: Not all the messages from your brain are seamlessly reaching your body. Every single thing your brain has to plan and carry out, from lifting a mug or swallowing a peanut to copying a dance step or following a map, will always be a little harder, will require a little more focus, will be more likely to go wrong.

I didn’t really understand. Hell, I’m still not sure I understand. But I got lucky. Living near the world’s first-ever Dyspraxia Foundation, parented by people who refused to consider that DCD might hold me back, enrolled in occupational therapy and later regular counseling, and surrounded by teachers who were often familiar with the condition—I mean, I was the luckiest accident-prone kid that ever lived.

Then, in 2012, I moved to the United States for graduate school and for the first time learned what it feels like to live among people who have never heard of DCD. Who wonder, sometimes out loud, if it’s all just in your head.

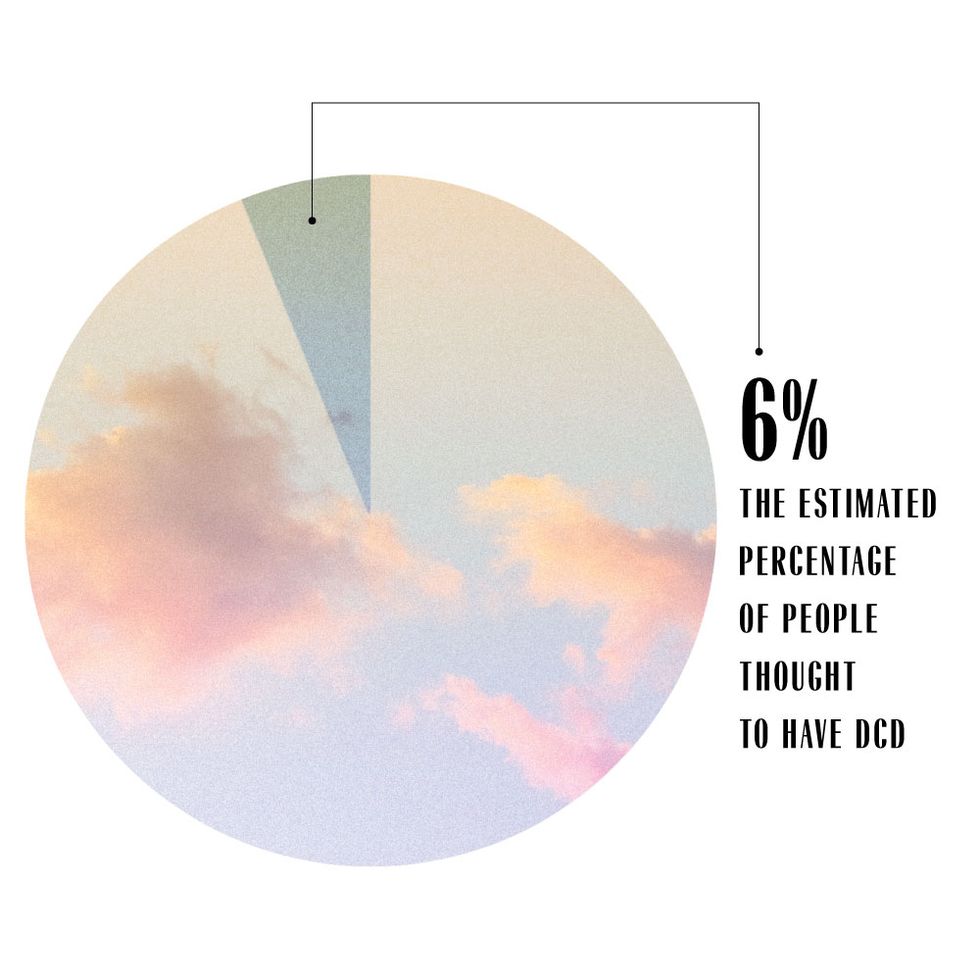

Roughly 6 percent of people worldwide have DCD. That makes it more common than autism spectrum disorder, which is thought to affect 1 percent of the population, and close to being as common as dyslexia, which affects about one in ten people. You probably have a working knowledge of both. DCD, however, remains the redheaded stepchild of neurodevelopmental disorders, a classification the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders only formally gave it in 2013.

I’ve spent much of my life trying to communicate to people what I know to be true about my brain—that, yes, I am clumsy as hell, but it’s more than that. Well-meaning friends and family ask me to elaborate, and I can’t. I am an editor, a writer, a person whose career and mental health are built on undoing the threads in my head and putting words to them; I can process and articulate the technical aspects of my disorder as much as anybody with a disorder that gets in the way of processing and speaking can—but in 20 years, I have never, not once, gotten close to conveying what it feels like.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

It is not just about the effort it takes to do the simplest things. It’s about the way the world has to slow down for me to do them. If I get up from a chair, I have to consider my limb placement with the focus of a tightrope walker or else I trip—on my other foot, on the leg of the chair, on nothing at all. If I don’t chew my food carefully and in silence, I swallow the wrong morsel at the wrong time and choke on it; if I try to speak while I’m eating, I get overwhelmed and begin to quietly breathe faster, faster, trying to push myself to do this perfectly normal thing that is going out for dinner, until the edges of my vision are soft. This would all be fine if everybody else’s worlds were constantly slowing down too, but they aren’t. The people around you operate so easily, so fluidly, without pause, that you have to assume you’re doing it wrong. There’s a word for what they are—neurotypical—but it feels personal: They’re doing it right, and you're all wrong. That’s the rub with DCD: You’ve never known things any other way.

To live with DCD is to feel perpetually out of sync, to quote the title of the popular book by Carol Stock Kranowitz, an expert in motor and sensory issues—out of sync with the sounds you hear, the movements you intend to make, the space around your body, the concepts people describe, the ways you try to say, do, act, and process what surrounds you. Most of all, you are out of sync with the effortless way the people around you seem to exist.

If that sounds isolating, it is. It’s made more so by the fact that DCD rarely presents the same way in different people. Take my dad and my two brothers, for example, who also have DCD. (It’s hypothesized to have a strong genetic component.) My father and I, we’re famously clumsy, all elbows and flailing limbs, but he loves to eat (which I find overwhelming) and he was never able to ride a bike (which I can do). My brothers glide along beside us, taking easily to soccer, basketball, rowing, you name it—but one can’t write by hand to save his life, and the other has a hard time with his speech, the words flooding out all at once and spilling over one another.

“There are so many pieces to DCD,” explains Keith A. Coffman, the director of the Movement Disorders Program at the Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City. “Breaking it down into individual symptoms, or a small group of symptoms, is challenging.”

Nobody knows what causes DCD, and there is no “cure.” Before it was labeled a neurodevelopmental disorder, it had been posited to be a psychiatric disorder, a sensory disorder, a social disorder, a variation of cerebral palsy, and even “minimal brain damage.” DCD “likely has a baffling quality to most people,” says Linda Copeland, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician and professor at the University of California San Francisco-Fresno. “Teachers see bright, creative children who are not working to their potential. It becomes too easy to blame the child for being unmotivated or for misbehaving.”

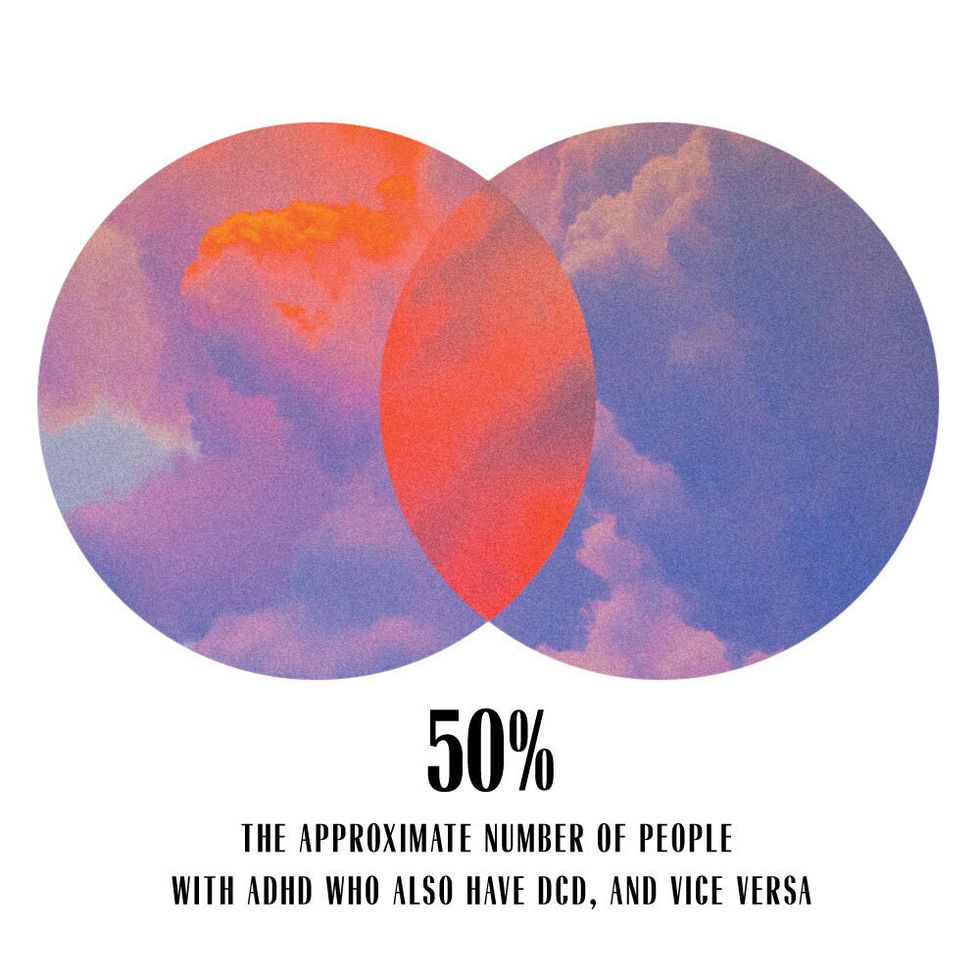

As many as half of people with DCD also have ADHD, and the same proportion of ADHD patients meets the criteria for DCD, so it is sometimes diagnosed as ADHD alone. Many others have it along with autism spectrum disorder or dyslexia. (More often than not, DCD isn’t the only disorder a person has.) Different countries and organizations refer to DCD using different terms, and even experts use a variety of words to describe it; support groups and Commonwealth countries tend to use “dyspraxia,” and North America and the research community lean toward “DCD.”

Unfortunately, DCD isn’t well understood in any country. But in a place like the U.S.—a country considered trigger-happy when it comes to brain diagnoses—the lack of acknowledgment of DCD feels astonishing. Put another way: If modest estimations are correct, more than 19 million people in America have DCD. Without a diagnosis, they’re left, at best, dimly aware that they’re palpably and inexplicably less capable than the people around them. At worst, they feel out of sync with every part of their daily life. Research has shown that children with DCD are far more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression—and those are the kids “lucky” enough to get a diagnosis.

In a piece for The Mighty, librarian Kate Reynolds writes, “Life before I knew I had dyspraxia was full of unknown terrors and humiliations.” But it was more than that, she tells me: “I always knew something was wrong, and I didn’t know what. I felt a great deal of shame. I thought maybe things were this hard to everyone and I was just a failure who never bothered to try hard enough.”

Like me, Warren Fried, now 39, was a clumsy kid who couldn’t zip up a jacket or draw within the lines. Unlike me, Fried grew up in the northeastern U.S., where the kids and teachers around him thought he was slow or lazy or both. Fried couldn’t recall simple instructions, connect with other students, or even process some of the words teachers used. “My childhood in general felt like a hopeless failure,” he says.

It wasn’t until Fried studied abroad in West Sussex, a leafy county in the south of England, that he received a referral, an evaluation, and, finally, a diagnosis from his college’s student services. He was 19. “In the U.S. education system, I was an enigma,” he says. Of getting a diagnosis at all— “I was very fortunate.”

It was then that Fried came across the Dyspraxia Foundation, founded in the late ’80s by Marilyn Owen and Stella White, who had met at a “clumsy children” physiotherapy group and were astonished by the lack of support available for their kids. These days, the foundation publishes an annual research journal, operates more than a dozen local chapters, oversees fundraising events and conferences, and hosts an annual Dyspraxia Awareness Week. Inspired by the success the U.K. has had with its foundation, Fried returned to the U.S. and, in 2006, founded Dyspraxia USA.

Fifteen years later, Fried’s organization remains the only dyspraxia/DCD-specific nonprofit in America. He’s happily married and a stay-at-home dad of 5-year-old twins, but his foundation only stutters along. Relying on donations and membership fees, Dyspraxia USA has just a few thousand “likes” on social media, no partnerships with research organizations or significant programs, and no employees aside from Fried. It brought in less than $35,000 in 2019, while the U.K.-based foundation raised the equivalent of more than $215,000 in 2019. (A disclaimer: I was invited to join the board of Dyspraxia USA in August 2019 and ultimately resigned in November 2020.)

It’s been a different story in the U.K. In part due to the U.K. Dyspraxia Foundation’s work, references to DCD dot British popular culture. The BBC featured a main character with DCD in the new Doctor Who. Cara Delevingne told Vogue in 2015 that she’s suffered from the disorder since she was a child. Daniel Radcliffe went public about his DCD diagnosis in 2008, explaining that he has trouble tying his shoelaces and was “crap at everything” at school. Emma Lewell-Buck, a member of Parliament since 2013, penned a HuffPost essay that proclaimed, “I am proud to be a person with dyspraxia.” And GCHQ, the British NSA, actively recruits people with DCD and dyslexia, citing their “spiky skills”—skill sets that combine poor abilities, like coordination, with abilities that test in the 99th percentile. (The same tests that were used to diagnose me revealed that I read about two and a half times faster than is typical.)

In the United States, there are no depictions of DCD on television or in film. (Believe me, I’ve looked.) Not one genuinely famous American has gone on the record about having the condition. There are some kids’ books about it—My Buddy Bryant: A Story of Friendship and Dyspraxia, for example—but that’s about it for DCD in American culture.

Working on this article, I tried to identify what went wrong for America. Although “clumsy child syndrome,” the original label for DCD, was established in the ’30s, the disorder didn’t make it into the American diagnostic bible, the DSM, for 50 more years. Recommendations from the Council on Children with Disabilities for screening children with motor delays didn’t go out until 2013. Dyspraxia USA was never successful in building a following, and Fried, who has no medical qualifications, remains a main resource for parents who Google their children’s symptoms and land on “dyspraxia.”

Probably the first and last time I’ll drive a car.

Most of the world’s foremost DCD experts live, practice, and publish in different countries, but eventually I tracked down Priscila Tamplain, PhD, a young professor at the University of Texas at Arlington and the U.S. representative for the International Society for Research Into DCD. Tamplain, who is originally from Brazil, is one of the only U.S. researchers who focuses on DCD rather than general motor difficulties (a large category that includes Huntington’s, Tourette’s, and Parkinson’s). I asked her why that is. “There’s a very clear reason for that,” she says, “and it’s funding. It’s very hard to get funding for disorders that you can’t streamline. You can’t find two children with DCD that are the same.”

I thought of my brothers and my dad. It barely feels like we share a disorder; we’re more likely to bond over a pizza topping than a common difficulty. “And it very rarely comes in isolation,” Tamplain adds. “It often comes with conditions like dyslexia, ADHD, autism, speech impairments, and so on, which are more prominent and more visible, in a way.”

Confusing things further: Not only does DCD usually go hand in hand with other disorders, its symptoms—challenges with movements big and small—often are features of those disorders. “Motor difficulties tend to be secondary for most of the population. They’re well-known to be associated with other conditions: intellectual deficits, autism, ADHD. But the core of DCD is motor difficulties,” Tamplain explains. “DCD is a disorder of exclusion. To diagnose it, we need to exclude a whole lot of other things.”

The odds are stacked against DCD, thanks to its wide swath of symptoms, its two different names, and its overlap with other, more “visible” disorders. But, Tamplain tells me, in the ’90s you could have said the same of autism, which went by a mishmash of different names and had a low profile. Then came Autism Speaks, a nonprofit that launched in 2005—just one year before Fried founded Dyspraxia USA—with a $25 million cash injection from billionaire Bernie Marcus and a dynamic business model. Now a behemoth of an organization, albeit a controversial one, Autism Speaks has funded half a billion dollars’ worth of research into the disorder, and it raised $94.5 million in 2018 alone.

I ask Tamplain what it’s like to be so fiercely committed to a cause that, for now, keeps running into dead ends. “I’m here, you know, just hitting the waves because I just love these kids,” she says. She’s talking about the children of the Little Mavs Movement Academy, a DCD motor-skill intervention program run by the laboratory she directs. People come from as far as Mexico to have their kids join Little Mavs. But every child with DCD that she works with has different issues, Tamplain says, which makes them difficult to study. “I think it scares the scientific field.”

Because there is no way to “fix” DCD, you can work to reduce the emotional, mental, and physical toll of the disorder, intervening at an early age as Tamplain does, but you cannot make it go away. It’s true that countries with universal health care have put more resources behind that work than the U.S. has; here, the for-profit medical system isn’t designed for long-term, individualized therapies, but that’s probably just one of the many reasons all of this happened. Well—didn’t happen.

I know I’m one of the lucky ones. It doesn’t make it easier. When you don’t have language for how and why your brain is misfiring, you spend your life bending away from the situations that leave you feeling more alone and ashamed and overwhelmed. I almost never try new things, from new restaurants (what if they’re noisy?) to new foods (hard to swallow?) or new hobbies (what if I can’t?). My friends joke that I’m new-experience averse, but I just want to make it through the day without being overwhelmed. When the directions don’t make sense and it’s hard to swallow your water and harder to enunciate, when you’re standing unsteadily and breathing rapidly and the seams on your clothes are scratching your skin—and it looks to everybody else like you’re just walking down the street, but it feels like you’re only just holding on to yourself? I don’t have the words for that. Oh, yes, don’t mind me, I’m just drowning in my own brain?

When I tell people I can ski, this is what I mean.

When you don’t have the language to communicate what you’re going through, for any kind of problem, that sense of confusion, of hopelessness, crystallizes into shame. Every time I watch somebody drive or dance or effortlessly glide across a room, I feel ashamed. It doesn’t make sense, because it’s not my fault, but I’m not thinking about that. I’m only thinking: I can’t do that. Look at them do it.

When I have kids, they’re probably going to have DCD. (I informed my boyfriend at, oh, month two that he’d be our family chauffeur. He has high hopes for the future of self-driving cars.) By then, I hope I’ll have figured out how to describe what feels like crossed wires in parts of my brain and holes elsewhere. I hope it’s better for them, but I don’t know. I hope they get the support I did, and I hope that when they tell people what’s going on with them, someone knows what that means.

For more information about DCD, visit Understood. See if you're eligible to participate in Tamplain’s study, the first in the U.S. to systematically document the struggles of individuals with DCD and their families, click here. Little Mavs is accepting donations.

Editor: Danielle McNally | Research: Henry Robertson | Art: Susanna Hayward

Jenny is the Digital Director at Marie Claire. A graduate of Leeds University, and a native of London, she moved to New York in 2012 to attend the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She was the first intern at Bustle when it launched in 2013 and spent five years building out its news and politics department. In 2018 she joined Marie Claire, where she held the roles of Deputy Digital Editor and Director of Content Strategy before becoming Digital Director. Working closely with Marie Claire's exceptional editorial, audience, commercial, and e-commerce teams, Jenny oversees the brand's digital arm, with an emphasis on driving readership. When she isn't editing or knee-deep in Google Analytics, you can find Jenny writing about television, celebrities, her lifelong hate of umbrellas, or (most likely) her dog, Captain. In her spare time, she writes fiction: her first novel, the thriller EVERYONE WHO CAN FORGIVE ME IS DEAD, was published with Minotaur Books (UK) and Little, Brown (US) in February 2024 and became a USA Today bestseller. She has also written extensively about developmental coordination disorder, or dyspraxia, which she was diagnosed with when she was nine.