"There Have Been Points in My Life When I Have Felt Like Feminism Was Not for Me"

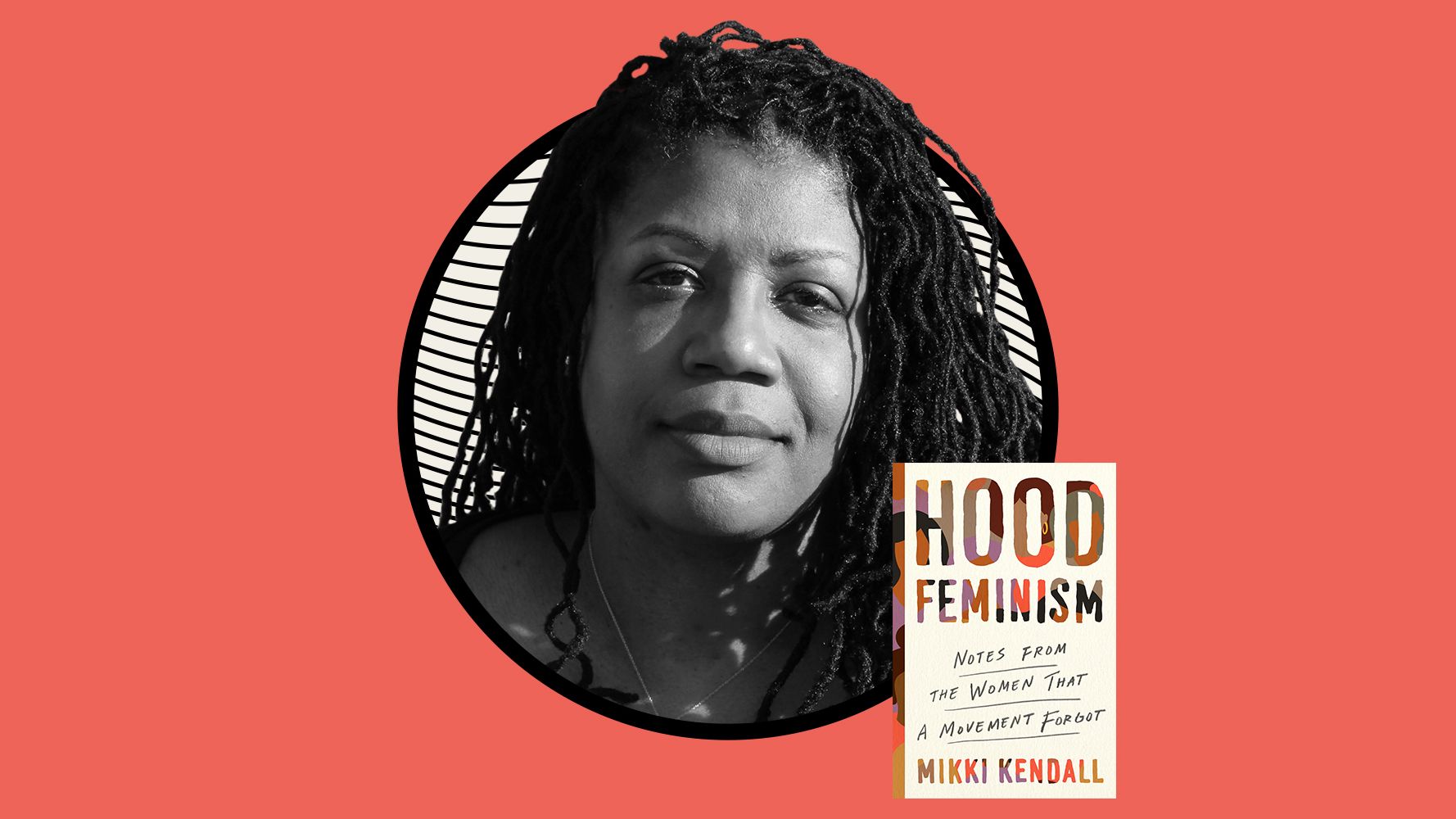

Mikki Kendall, author of Hood Feminism, on how the mainstream feminist movement has largely ignored women of color.

Behind the facade of millennial pink and Rosie the Riveter posters, mainstream feminism has largely ignored an entire population: marginalized women. In Hood Feminism, Mikki Kendall argues with searing prose that because mainstream feminism is so focused on elevating more (usually, white) women into CEO positions, it has neglected the foundational needs of many Black women—things like food security, education, and childcare.

Cutting, critical, and consequential, Hood Feminism is required reading for anyone who calls himself or herself a feminist, an urgent piece of feminist discourse. It's a tough read—especially if you've been giving yourself woke feminist gold stars—but that makes it all the more necessary. At this moment when the Black Lives Matter movement has swept the nation and the demand for racial justice has grown louder than ever, we spoke with Kendall to learn more about the failures of the mainstream feminist movement and how it can change—must change—for the better. Here, Kendall shares a few pillars of her argument, but pick up your own copy to understand the breadth of the conversation.

Marie Claire: What does the term "Hood Feminism" mean?

Mikki Kendall: I would say it's lived feminism. The feminism that is the work that you do for your community, for yourself, and for your family. It’s less about the academic end, or about becoming a CEO, and more about survival and sustainability for the long-term—for your community and yourself.

MC: In the introduction of Hood Feminism, you write: “The hood taught me that feminism isn't just academic theory.” Can you expand on that?

MK: A few years ago, I was the target of a lot of backlash for writing about medically necessary abortion. What was jarring was that there were plenty of people who wanted me to testify [about abortion], but it was my community that said, “Are you safe? Do you have enough food? How can we help you?” It was less about advancing my thought [on medical abortion].

MC: Was that a moment that helped shape your theory of feminism?

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MK: Yes. But it's not like that was the only time—there have been various points in my life when I have felt like feminism was not for me or spoke to me. A lot of feminist texts, especially academically centered texts, engage with low income Black women who are single mothers like we're objects, like we're problems to solve.

I really wanted to talk about what I saw day to day, as opposed to what people think happens. There's this weird narrative that the hood is a terrible place, and that no one takes care of anyone and you're out there struggling by yourself. The reality for poverty, whether you're in the inner city or a rural area, is that you are with your community all the time. You're all working together, because otherwise you're not going to make it.

MD: You argue that feminism has largely ignored the problems that many Black women and women in poverty face: things like food security and education. Why is it crucial to view those problems through a feminist lens?

MK: When we say a feminist movement is for women, it's supposed to advance equality for all women. But then we say that these issues that only some women face [like food insecurity or education] are someone else's problem. Well, then we're not a movement for all women. We're a movement for women who want to be a CEO, we're a movement for women who want equality with white men. We're a movement for a lot of things, apparently, but we're not a movement for women who need support in their struggles. Then, mainstream feminism often turns to these women and says, Why aren't you showing up for us? Solidarity can't be a one way street.

We're a movement for a lot of things, apparently, but we're not a movement for women who need support in their struggles.

MC: Can you describe your relationship with the word solidarity?

MK: I think it's a great idea to have each other's backs, but it seems like often the actual having of the back is more likely to happen between communities of color and between feminists of color.

I feel like sometimes the concept of solidarity becomes a trap. It's not that it's take a penny, leave a penny in terms of support. I understand sometimes it's going to be 60–40. But when your idea is 99–1, that's not solidarity.

MC: It brings up an interesting illustration: Take the Women's March, for example, which had a huge turnout. Where are all the people who were part of that movement now, during Black Lives Matter protests?

MK: It’s interesting to see people suddenly realize as the videos [of injustice against Black people] roll in back to back to back: Oh, wow, this is really bad. Well, it was really bad eight years ago. It was really bad 16 years ago. The videos have made it easier to see. Tamir Rice was killed at a park at 12 years old. So, there's something sort of jarring about how feminism as a movement didn't figure out back when Rekia Boyd was killed [in 2012], that maybe Black women are in danger from police. I've seen some now with Breonna Taylor go, Oh, police brutality affects Black women. But we had that conversation with Daniel Holtzclaw and his victims, and we've had that conversation with Rekia Boyd.

I just want feminism to show up. I understand that for the most part, upper middle class white women don't have anything to fear from police. The police will not use your name or your safety as a justification for their behavior. We need you to show up and say something.

MC: Why is prioritizing intersectionality crucial?

MK: At this point, there's a weird sub narrative. We think somehow that all women are safer regardless of race, right? Really, women, especially women of color, aren't any safer [than men]. They're in more danger. And in some cases, like for indigenous women, there are higher levels of risk for certain crimes like sexual assault.

People are starting to realize that those women aren't safe. You can find any number of mainstream feminists who will be happy to tell you about the work they've done in the Congo or in India. Then when you start asking them about educational access in America, or about gun violence that particularly targets girls who are often of the same racial background as the ones that they feel like they can go save, [feminists] don't seem to recognize that [those American girls are] people. Some of that is definitely about being able to go and feed this white [savior] complex and feel good about yourself.

You might also have to face the fact that the people oppressing women of color are your neighbors. Are your relatives. Are you. There's a point where I think it's almost painful for feminism to look at the work it didn't do. It's easier in some ways to go clean up someone else's house than to clean your own.

MC: As people start to acknowledge and understand their implicit bias and try to become better anti-racists, better allies, how do we separate that from the problematic white savior narrative?

MK: I do think some people are trying to be better. They want to be better. They want to be helpful. They want to be in solidarity. But then there's also this: [Feminists] don't want to be infantilizing. We don't want to be in this moment where white saviorism trumps the work that Black people are doing. How do we look at that? I would argue that that's where [people need to show up]: at the voting booth, school board meetings, and municipal meetings. Municipal meetings are the most boring things in the history of humanity. But those are the places where the hard work of change happens. Showing up in these ways probably won't get you as many savior cookies, but you can be super effective if you use your privilege to make sure things are better for a community, as opposed to just for you.

MC: Why do you think mainstream feminism hasn't acknowledged the cracks in the facade? Is it fear of weakening the movement, or do you think people are actually ignorant of the plight that many women of color are facing?

MK: There are people who identify as feminist who are as racist as the day is long. They are perfectly fine with the idea that white women will get ahead, or some women will get ahead, and they have attached a value system to which women deserve to get ahead. Then you add in classism. Low income white women have a lot more in common with low income Black women than they do with middle class or upper middle class white women, right? I know that they are often blamed for racism, but they don't functionally have any power to make racism as a structural oppression work. You know who does? Rich white people. They want that access, that freedom, that opportunity. But what they're really chasing is equality to oppress, not equality for all.

I don't think it's just ignorance. I think some people are ignorant. I think some aspects of this are definitely "the bubble." I know people like to say a liberal bubble, but really, the bubbles are not in the big city. The bubbles are in your small town Americana. And they're there because your parents or grandparents moved you to a sundown town or built a sundown town. They deliberately voted to avoid integration. If you live in a place that's all white or 99 percent white, that's not organic. That didn't happen by accident. When you say, "My town has no problem with racism," you're choosing ignorance at the expense of other people. It's not that feminism doesn't know better. I think feminism doesn't want to do better all the time.

It's not that feminism doesn't know better. I think feminism doesn't want to do better all the time.

MC: Recently we've seen the commodification of white feminism by major brands. What are your thoughts on that?

MK: I’m going to bring The Wing in as my example. And they're not the only one. Con artists can show up anywhere, and you know who's the easiest to con? People who want to be part of something. A lot of corporations are saying, we can give you something exclusive. Business are selling you this special space devoted just to you.

One of the passages in that [New York Times] exposé [about The Wing] described someone who had a tantrum and was throwing things at a staffer. I would bet money that that's a person who behaves that way, period. Those people are by and large enabled by their money, yes, but also by the fact that there's always someone selling this idea that they can have something exclusive. There's always a way to create an exclusive bubble. And I think a lot of businesses, even though they say their state of intent is to be for women, a lot of them are just hucksters taking advantage.

MC: What else is on your mind?

MK: A few things: One: Trans women are women. Trans men are men. Nonbinary and genderqueer people exist. No one's identity, safety, or humanity should be up for debate or discussion. Trans exclusionary equals bigotry.

Two: Childcare is one of those spaces where feminism remembers that there are costs. Childcare subsidies are an often-neglected part of the conversation around public assistance. If we want women to be empowered to work [especially during the COVID-19 pandemic], we have to make it possible for them to be able to go to work, even if they have children. I would love to see us remember the purpose of social safety nets. There's a reason that public housing and other assistance programs exist. It's not that they're handouts; it's that they're "hand ups." No one in bootstraps can lift more than their legs.

For more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.

RELATED STORY

Megan DiTrolio is the editor of features and special projects at Marie Claire, where she oversees all career coverage and writes and edits stories on women’s issues, politics, cultural trends, and more. In addition to editing feature stories, she programs Marie Claire’s annual Power Trip conference and Marie Claire’s Getting Down To Business Instagram Live franchise.