Vanishing Act

Her life in South Korea seemed perfect: new friends, a burgeoning career, reality-TV fame. But she was about to become notorious—disappearing without a trace, only to reappear pledging allegiance to North Korea. What happened to Lim Ji-hyun?

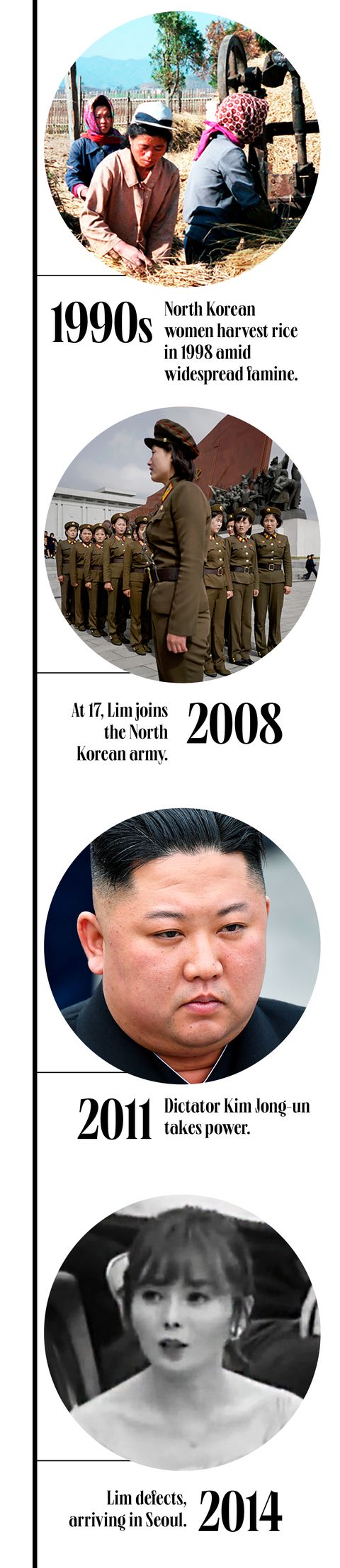

Under the cover of nightfall, former North Korean soldier Lim Ji-hyun risked death to escape her homeland, the most isolated and ruthless dictatorship on the planet. Somehow, the then-23-year-old made it to safety in Seoul, the ultramodern capital of South Korea. Perhaps she paid Chinese brokers to sneak her across the Chinese border, as other North Korean defectors have been known to do. However she got there, by April 2014, Lim had begun a seemingly successful new life in her adopted country. With girlish looks and a gift for comic storytelling, she quickly became a rising media star. Petite with wavy brown hair, the defector amassed an online fan club that followed the video diaries she posted, which revealed details about her previous life in the North. On her 26th birthday, in April 2017, she wrote on her blog, “This is possibly the happiest birthday of my life. Thank you to all the fans who love me—you give me the courage to keep speaking out.”

Later that month, Lim vanished.

Her social-media channels, usually updated frequently, went silent. In her pink studio apartment in the trendy district of Gangnam, her clothes, beloved stuffed-animal collection (frequently a cute backdrop in her vlogs), and other belongings remained untouched. Police investigating the case revealed she had also left the equivalent of almost $20,000 in her South Korean bank account. “She didn’t tell anyone she was leaving, not even close friends like me,” says Seoul-based fellow defector Sun-hi, 29, who doesn’t want her full name published in order to protect her identity. “We assumed she had gone away on a shopping trip, but we knew something was badly wrong when she didn’t return,” Sun-hi says, speaking through an interpreter.

Lim is among dozens of mostly young and female North Korean defectors who, in recent years, have become popular in South Korea’s glitzy entertainment industry. Appearing on talk shows, reality-TV programs, and dramas, the “Northern beauties,” as they are known, use their newfound liberty to expose the harshness of life inside the secretive Communist state. The women chat with incredulous South Korean hosts on topics ranging from the North’s excessive ban on “Western evils,” like blue jeans or pop music, to the horrific public executions by firing squad. (According to a 2019 study by the South Korean NGO Transitional Justice Working Group, out of 610 defectors interviewed, 83 percent had witnessed at least one public execution.) Lim was an audience favorite on the talk shows, says Sun-hi, who is also a regular. “Ji-hyun was a natural,” she says. “She could make people laugh and cry at the same time, and she always enjoyed herself.”

For South Korea’s authorities, Lim’s sudden disappearance was far more high-stakes than a regular missing-persons case. During decades of brutal misrule and deprivation since the Kim dynasty took power in North Korea in 1953, almost 34,000 North Koreans have escaped to the wealthier democratic South. The defections are humiliating for the North Korean regime and aggravate the bitter political rivalry between the two sides of the peninsula. Current dictator Kim Jong-un, 36, who took office in 2011 after father Kim Jong-il’s death, has a particularly harsh view of escapees. “Kim Jong-un takes defections very personally,” says Kang Myung-do, a North Korean defector and former professor of political science at Seoul’s Kyonggi University. “He regards such acts as treason against the fatherland and will go to extreme lengths to get revenge or recapture so-called traitors.”

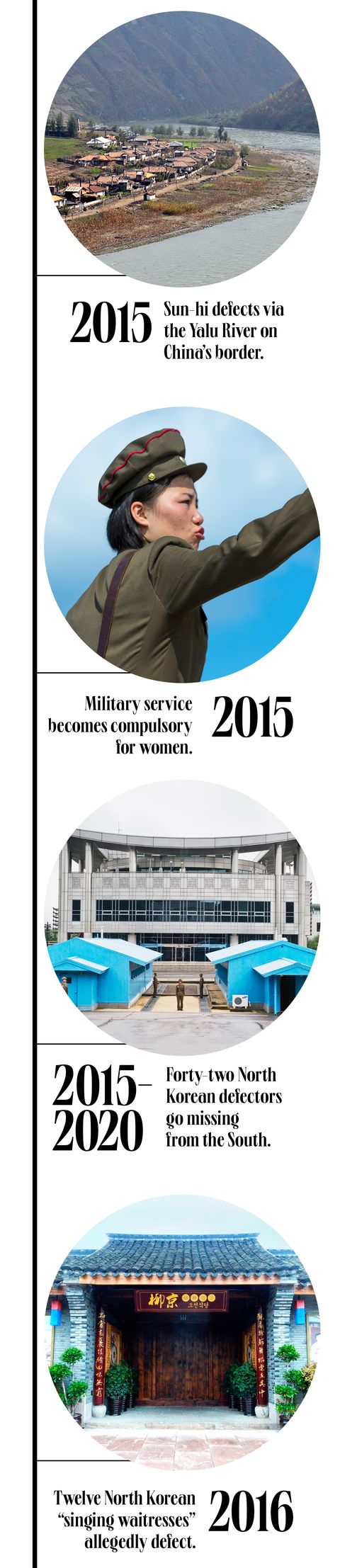

According to South Korea’s Ministry of Unification, which oversees issues relating to the two Koreas, Lim is one of 42 North Korean defectors who have gone missing in the South in the past five years. “Most of these disappearances are unexplained, but there is strong suspicion of abduction or other foul play by the bowibu [North Korean secret police] in some cases,” says Kang. When Kim Jong-un—a millennial who was privately educated in Switzerland—came to power, many hoped that he would ease the draconian policies of the past and begin to open up the country. In fact, says Kang, he has clamped down harder. A month before Lim vanished, Kim allegedly ordered his secret police to escalate kidnappings of defectors and return them to the North. The directive, according to Kang’s sources inside the country, was possibly in retaliation for the dramatic alleged mass defection in April 2016 of 12 “singing waitresses” who worked at a state-owned North Korean restaurant in China (a tourist attraction designed to earn foreign currency for the cash-strapped government). “It was a sensational case,” says Kang. “Kim accused South Korea of somehow tricking the women into defecting, but his repeated demands that the women be sent back [to the North] fell on deaf ears.”

High-profile escapees such as Lim are at particular risk, says Kang. “Celebrities like Lim who talk on TV have a huge target on their backs. Women like her are the whistleblowers of North Korea.” By focusing on the details of everyday life in their television appearances and social-media posts, such female defectors leak the shameful secrets that Kim Jong-un badly wants to hide: food and electricity shortages, poverty, and the ruthless oppression of ordinary people. Women also defect in far greater numbers than men, adds Kang—in 2019, women made up 81 percent of the 1,047 North Koreans who defected to the South, according to the Ministry of Unification—for reasons including widespread gender abuse and discrimination at home, the desire to support their families financially, and attraction to the additional freedoms for women in the South, as portrayed in bootleg TV shows and movies.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

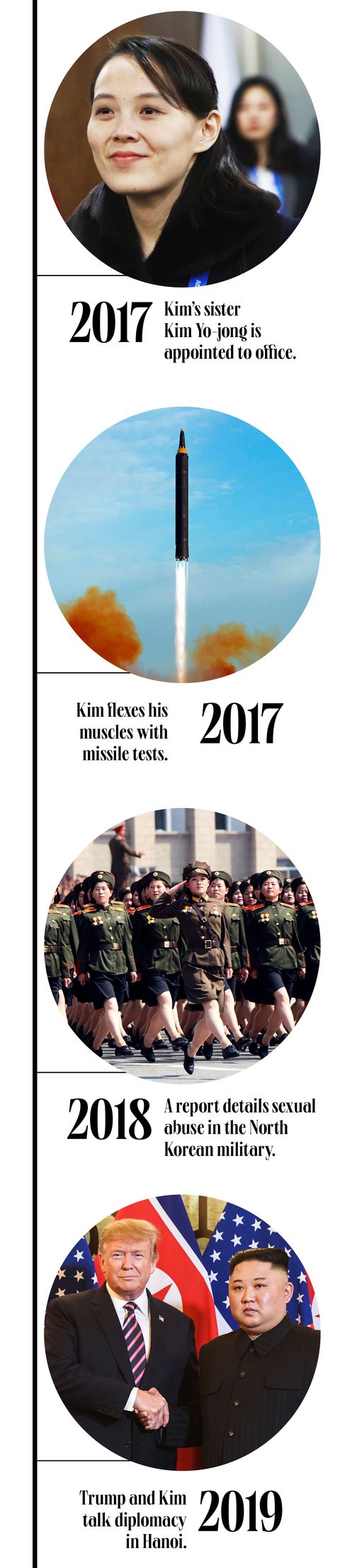

While North Korea purports to champion equal gender rights, in reality, according to the U.N., discrimination is endemic in higher education and the workplace, and women are more likely to be malnourished and denied access to basic health care. Women’s appearance and behavior are rigidly policed; wearing pants is banned in many places, as is having long hair if a woman is over 30. A 2018 report by the London–based activist group Korea Future Initiative found that “multiple forms of sexual violence” are pervasive in institutions such as the army and government and across society as a whole. “Misogyny lies at the core of the Kim dynasty and manifests in numerous ways, including male privilege, sex discrimination, and patriarchy,” read the report. South Korea’s record on gender equality is far from perfect—the nation ranks 108th out of 153 countries in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index—but women there enjoy far more social and economic freedoms than their sisters in the North do.

Even before Lim vanished, there were signs that some in North Korea wanted to silence her. In late 2016, North Korean propaganda news websites and social-media channels began linking to grainy photos of a young woman in various sexual poses. Although the body parts were censored, it was clear the woman was naked. The news sites claimed it was Lim and that she was working as a webcam prostitute.

“This was a smear campaign against Ji-hyun,” says Sun-hi, designed to shame Lim and ruin her career in the South. “This has happened before to defectors who become TV stars.” An estimated 60 percent of women who flee North Korea by crossing the border into China—the most feasible escape route—end up being trafficked into forced marriage or the sex trade, according to a 2019 Korea Future Initiative report. Sun-hi says there is no evidence that this fate befell Lim. “Ji-hyun was devastated when the images started circulating and went to the police. The police analyzed the videos and photos and confirmed to the public that the woman in the photos was not her.”

As if the smear campaign wasn’t chilling enough, the fact that Lim was possibly abducted has affected everyone on the North Korean–defector celebrity circuit. “We thought we were safe in Seoul, but suddenly we felt that we had to look over our shoulders all the time,” says Sun-hi. “It was terrifying not knowing what had happened to her.” Kim has toughened punishments for anyone involved in defections. According to the Seoul-based Korea Institute for National Unification, which produces an annual report on human rights in the North, penalties range from being shot and killed to being sent to a hard-labor camp for five or more years. “Everyone knows that going to a labor camp is basically a death sentence. There is no food or medicine, and people freeze to death in winter,” says Sun-hi. “Being recaptured is our very worst nightmare.”

Speculation mounted about Lim’s fate, and the police investigation continued, but no one in South Korea was prepared for what came next. In a staggering twist, in July 2017, three months after she disappeared, the TV star resurfaced in North Korea. In a video uploaded to a propaganda site run by the government, Uriminzokkiri (“Our Nation”), a tearful Lim claimed she had returned home to the North of her own free will. “Every day I spent in the South was like hell. When I was alone in a cold, dark room, I was heartbroken, and I wept every day, missing my fatherland and my parents.”

Her real name was Jeon Hye-sung, she said, sitting at a wooden table against a blank white wall in what looked to be an anonymous government office. Her appearance was almost unrecognizable: Her long, wavy hair had been cropped boyishly short, and she wore a traditional long hanbok silk gown in place of the fashionable Western dresses and streetwear she had favored in Seoul. Her fans in the South quickly commented on social media that her eyes looked drawn, as though she had been crying, and that her face “looked pale and puffy.” They theorized that her thick, ghostly white makeup was possibly covering up bruises.

Denouncing herself as “human trash,” she begged for forgiveness from Kim Jong-un.

Lim claimed in the 29-minute video that she was now back living with her family in the western city of Anju. “I went to the South harboring the fantasy that I would never go hungry and could make a lot of money,” said Lim, who was a young girl during the nationwide famine that killed an estimated 1.5 million North Koreans in the mid- to late 1990s. “The reality of the South was very different,” she continued. “I was forced to work in sleazy bars to make money, and nothing worked out.” Denouncing herself as “human trash,” she begged for forgiveness from Kim Jong-un for “betraying” her family and her country. “I committed a terrible crime. I am worthless. I do not deserve to live.”

Lim appeared in two further videos condemning the “capitalist South”—one in August 2017, this time wearing a demure pink jacket, and another in February 2018, wearing a sparkly brown top. In both videos, she had the same cropped hair and tired look around her eyes. Her location in a blank-walled room, with only a potted plant and a plastic water bottle as props, gave no clue as to her whereabouts. Speaking straight to the camera, she repeatedly shot down suggestions that she’d been kidnapped as “downright lies and fabrications,” claiming she had traveled from South Korea to northern China and swum across the Yalu River between China and North Korea to “reach the bosom of the fatherland.”

Lim has not been seen since. As of press time, South Korean authorities are still trying to get to the bottom of her case. Seoul police spokesman Park Tae-joon says that despite Lim’s denials in the propaganda films, they firmly believe she was coerced into returning. “Our intelligence suggests Ms. Lim was tricked into going on a trip to China so North Korean government agents could kidnap her and take her back across the border,” says Park. “Ms. Lim was told that a large sum of money, around $10,000, that she had tried to send home to her parents through a Chinese middleman had gone missing. She hurried to China to retrieve it, but we think it was a trap.”

Middlemen or brokers help defectors escape and also make contact with their families back in the North. South Korean investigators believe Kim Jong-un has ordered his secret police to infiltrate these broker networks and recapture escapees. While there is no absolute proof that Lim was abducted (at least, none the authorities are revealing), a Ministry of Unification spokesperson says the number of defectors who return voluntarily is tiny. “Since 2012, only 25 people [out of 10,417 defectors] have gone back to the North freely. Of those, five later re-escaped back to the South.”

The mystery surrounding Lim has the murky depths of a spy drama, and political scientist Kang says her value as a propaganda tool for the North Korean regime cannot be overstated: “Their whole purpose [in kidnapping Lim] would have been to use her return as a PR coup to make the South seem evil and to deter other young women from escaping in large numbers.” Whatever her real feelings, Lim would have had no choice but to become a mouthpiece for Kim Jong-un’s tyrannical regime. “The officials would have threatened to kill her and her family if she didn’t say exactly what they wanted,” he says.

Over coffee and a walnut tart in a Seoul delicatessen, Lim’s friend Sun-hi, tall and chic in an all-black outfit and high ponytail, professes there were no signs that Lim was unhappy with her life in South Korea. “Naturally, we all miss our family and friends back in North Korea,” she says. “It’s the place where we grew up, so it’s normal to feel nostalgic. But Ji-hyun never talked about returning. Her dream was to become a serious actor, and she was full of optimism about her future here.”

Lim told Sun-hi she defected in 2014 by crossing the Yalu River, which runs along part of the 880-mile border between North Korea and China. She traveled for about two months through China and Southeast Asia to get to South Korea. “The border with South Korea is too heavily armed to cross, so the only real option is to cross the river into China,” she says. Sun-hi doesn’t know the exact details of Lim’s journey, but Sun-hi herself took a similar route when she defected with her younger brother in 2015. “We crossed the Yalu River in our underwear with one set of dry clothes each in a bag balanced on my head, and I also carried a bottle of bleach. My plan was to drink the bleach if we got caught. I knew I would rather kill myself than be forced to go back.”

Taking the same petrifying risk, Lim defected partly to support her family, says Sun-hi, who met her on the TV circuit about a year before she disappeared. “She told me her father worked in a big chemical factory, but he developed breathing problems and had to retire,” Sun-hi says. With dire shortages of basic drugs in North Korea’s state-run health-care system, Lim needed foreign currency to buy medicines for her father on the black market.

Like many North Koreans, Lim struggled when she first arrived in Seoul. Although all defectors receive a 12-week training course, housing, and financial assistance from the Ministry of Unification to help them adjust to their new lives, they often face job discrimination and other forms of prejudice in South Korean society. “It’s true that she had to work as a waitress in bars in the early days, but not for long,” Sun-hi says.

Lim’s pretty face and lively personality helped her find television work. The defector reality-TV genre is popular among South Koreans, who are deeply curious about the despotic regime on their doorstep. Lim appeared in a few programs, including Moranbong Club, a garishly lit talk show featuring “confident and courageous beauties from the North” telling stories that are by turns humorous and heartbreaking, often accompanied by tacky sound effects such as machine-gun fire or foreboding music. In one episode, Lim, dressed in a North Korean female soldier’s uniform to highlight her past, made the audience laugh with a tale of how she used to sell bootleg alcohol to survive when she was a schoolgirl, bribing her teachers with cigarettes when they heard her schoolbag clinking with glass bottles. “I would smile sweetly and tell customers the cheap rice wine was a limited edition to make them buy it. It worked every time,” she said, giggling.

She also appeared on a dating show called Love Unification: Southern Man, Northern Woman, which pairs South Korean men with young, attractive North Korean women. “South Korean men have this fantasy that we are more traditional and passive than modern South Korean women, so that’s the appeal,” Sun-hi explains. The show plays on social differences for comic or dramatic effect, such as a tech-ignorant Northern woman not understanding a microwave oven or a pampered Southern man being too squeamish to pluck a chicken.

Sun-hi rolls her eyes a little at the show’s regressive concept but says the upside of the light-entertainment boom is that it helps connect Koreans from both sides. “The shows give us a voice and a human face that is different from the usual miserable stereotypes,” she says. “For women, it proves we can be talented and funny and just as glamorous as women from anywhere else.” In Lim’s emotional video confession from the North, she blasted the genre, saying it is “designed to make North Koreans seem barbaric and stupid.” But Sun-hi says Lim reveled in her minor-celebrity status and regarded it as a positive career stepping stone. (The producers of Moranbong Club and other shows declined to be interviewed, saying the subject of Lim was “too political.”)

While most of Lim’s TV appearances were fairly lighthearted, Sun-hi believes she may have been targeted by the North Korean regime because of her blog posts. At first, they were mostly upbeat newsletters about her delight in discovering South Korean fashion and pop culture, but in the lead-up to her disappearance, they had begun to take a darker turn in describing her experience in the military.

Lim joined the North Korean army when she was 17 (though military service in North Korea was voluntary for women when Lim served, Kim Jong-un made it compulsory in 2015) and spent the next few years in a female artillery unit. “She started to post about the terrible conditions and abuse suffered by female soldiers,” says Sun-hi. While never admitting she experienced sexual abuse personally, Lim mentioned how male officers would handpick the prettiest female soldiers to have sex with and how some women were “given” to male soldiers for a night as a “reward” for loyalty or bravery. “I think her time in the army preyed on her mind, and she wanted to speak out,” says her friend.

Lim’s blog page was quickly taken down by the company that hosted the website after she re-emerged in North Korea, so exactly what she said in her posts and videos can’t be easily determined. But Lee Soon-sil, a Seoul-based defector in her 40s who worked as a nurse in the North Korean army before she escaped in 2007, confirms that sexual violence toward female soldiers was rife. “I treated cases of rape and assault every day,” she says. “Women would come to me with bleeding between their legs and injuries after they’d been beaten for resisting.” Senior officers, says Lee, viewed it as their right to choose women for sex, while lower-ranking male soldiers would often rape female colleagues and get away with it. “Rape was against the rules, but in practice it was never punished,” says Lee, adding that women seldom became pregnant because their periods usually stopped due to the harsh conditions. “There were serious health problems,” she says. “Women got sick from bad food and water, severe exhaustion, rat and insect bites, and many other things.”

I think her time in the army preyed on her mind, and she wanted to speak out.

Until recently, North Korea had almost no women in positions of power who could inspire the younger female generation; the top echelons of government and industry are overwhelmingly male. In the past few years, however, Kim Jong-un has elevated his younger sister, 33-year-old Kim Yo-jong, to a much more influential role, appointing her to the ruling Politburo in 2017. At the second meeting between Kim and then–U.S. president Donald Trump in February 2019, the diminutive Kim Yo-jong, who studied computer science in college, was the only woman at the table. North Korea watchers believe her increased visibility is no accident and that, at least in part, she is being used as a female role model to counter the allure of the South. So far, however, Kim Yo-jong has shown no signs of being any less tyrannical than her brother: In June 2020, she was allegedly investigated by the South Korean government for ordering the bombing of a liaison office on the border that had been built to improve relations with the South.

Sun-hi believes that the answer to her and Lim’s and countless other female defectors’ plight lies not in a different gender coming to power but in a total change of regime back in her blighted homeland. She accepts that she may never know what really happened to her friend—Kang speculates that Lim could have been executed or sent to a gulag once North Korean officials had no more use for her as a propaganda tool—but Sun-hi refuses to give up on her. “I will never believe that Ji-hyun returned out of loyalty to the Kim regime, and I hope to hear the truth from her in person some day in the future.” In the meantime, Sun-hi must live with the daily fear that—until the Kim dynasty is firmly in the past—she or any defector in the South could be snatched back to the “fatherland” and suffer the same fate.

This story appears in the Spring 2021 issue of Marie Claire.

Timeline images: Women working in field: Kathi Zellweger/AFP/Getty Images; soldiers: Ed Jones/AFP/Getty Images; Kim Jong-un: Yuri Smityuk/TASS/Getty Images; Lim: video screengrab; Yalu River: Bob Yue/Getty Images; soldier: Eric Lafforgue/Art in All of Us/Corbis/Getty Images; Panmunjom: Mark Edward Harris/Getty Images; Ryukyung Restaurant: Imaginechina/AP Images; soldier: Kim Jae-Hwan/AFP/Getty Images; Lim: video screengrabs (2); Anju: Ed Jones/AFP/Getty Images; Kim Yo-jong: Patrick Semansky/AFP/Getty Images; Rocket Launch: KCNA via KNS/STR/AFP/Getty Images; soldiers: Pedro Ugarte/AFP/Getty Images; Trump: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images