'Period. End of Sentence.' Invites Us to Reimagine the Menstrual Equity Movement

Fellow menstrual equity author Jennifer Weiss-Wolf dissects Anita Diamant’s new book, offering key takeaways in the fight for period justice.

When The Red Tent—Anita Diamant’s fictional chronicle of the biblical life and times of Dinah, daughter of Jacob and Leah—was published in 1997, it garnered a devoted following, making the rounds among feminist book clubs and religious scholars. So beloved was the book, that it was transformed into a television miniseries in 2014. In many ways, Diamant’s revelations of ancient camaraderie and community—and all the connectivity conferred by menstruation—served as an early harbinger for today’s modern movement for menstrual equity. And now, nearly 25 years later, she has released its encore: Period. End of Sentence. A New Chapter in the Fight for Menstrual Justice (out today).

The inspiration for the book is the 2019 Oscar award–winning short documentary film bearing the same name, created and produced by a group of Los Angeles students and educators via a school club they’d formed; their mentor and teacher, Melissa Berton, provided the book’s foreword. After the film venture morphed into a global education and advocacy initiative called The Pad Project, Diamant endeavored to create a fresh, up-to-date resource that could further inform and energize the next generation of menstrual activists.

The pages of Period. End of Sentence. are filled with rich personal testimonies, details on political organizing strategy, and Diamant’s own wisdom on issues ranging from religious rituals surrounding menstruation to pop culture celebrations of periods to menstrual product marketing critiques. Woven throughout are powerful firsthand accounts from activists and everyday people alike: of bittersweet first (and worst) period stories, of grappling with the trauma of period poverty, and of surviving deeply held stigma and shame. Diamant knowingly and lovingly represents it all—with the keen eye of a reporter, the soul of a storyteller, and the voice of a trusted narrator. Her commitment to social justice and dignity for all shines through.

As an outspoken advocate for menstrual equity myself, Period. End of Sentence. offered an opportunity for reflection on ways to reimagine and reinforce the collective impact of our movement. Below, my top takeaways from the book.

Our stories matter—including (and especially) stories from those who lack agency.

Diamant discusses the robust legal and policy agenda underway in the United States (2021 policy goals are mapped out here). But it’s personal stories—like the many she shares—that are the lifeblood of organizing: they help enable better, more inclusive, and more meaningful policy for the very people the laws are intended to serve.

Take for example the justice system, which has been a focus for reform. As Diamant highlights in the book, legislatures in 13 states and several major cities, like New York and Los Angeles, now require menstrual product accessibility for people who are incarcerated; Congress mandates the same for federal prisons.

But the law remains silent when it comes to those in police custody. Last summer, as people across America took to the streets to protest racial injustice, I met a woman who shared with me the harrowing details of her overnight arrest for peaceful demonstration. On her period at the time, she was denied even toilet paper while detained. Eventually, she managed to remove her saturated pad—handcuffed, with the help of a cellmate, and in plain view of all—only to be left to bleed for many more hours. Her account became my fuel to recalibrate advocacy to expand the reach of laws that address menstruation, detention, and incarceration so that they cover everyone in the sprawling system. Diamant’s book fully reinforces this goal.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

We need to reexamine menstrual access in schools.

Period. End of Sentence. (the book and the film) zeros in on youth and education. As a result, I’ve been moved to reexamine the strength and scope of laws mandating menstrual access in schools—especially in light of a new study showing that 1 in 10 college students have been unable to afford menstrual products during the pandemic. Women of color experienced disproportionate harm: nearly a quarter of the Latina respondents and 20 percent of Black respondents reported enduring period poverty regularly; rates were also higher among first generation college students.

Yet laws tackling menstrual access often fail to meet the needs of those most at risk. Six states now require that pads and tampons be provided in secondary schools. But what happens when those schools are shuttered—due to the pandemic, as many experienced this past year, or even for summer break? Given startling rates of period poverty among college students, how do we pivot to ensure campuses are not excluded from state mandates? (Earlier this month, Washington state passed a new law extending menstrual product provision to its colleges and universities—a good start!) These are key considerations that must be baked into the next generation of policy development. Diamante’s narrative supports this expansive approach.

'Melissa Berton (center) and Rayka Zehtabchi (right) accept the 2019 Oscar for best documentary short film for Period. End of Sentence. '

It’s time to think globally—and take notes.

Leaders around the world are making sweeping change. Since Diamant’s book went to print, a grocery chain in Ireland began offering menstrual products free of charge to shoppers. At the start of the year, Scotland became the first country to mandate the provision of free period products to anyone in need. New Zealand will now do the same in all of its schools.

Here in the United States, calls for a nationwide, whole-government approach to menstrual equity have fueled key changes in Congress—some of which are referenced by Diamant, like the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which now allows menstrual products to be purchased with pre-tax dollars via health savings and flexible spending accounts. There are other federal advances, too: Pads and tampons are among the essential items that can be accessed with certain federal emergency grant funds; the Veterans Health Administration must make menstrual products freely available in all VA facilities.

Still, we can and need to do more. New federal legislation worth getting behind includes the Menstrual Equity in the Peace Corps Act to ensure access for our national volunteers, along with the reintroduction of the Menstrual Equity for All Act. This bill is designed to alleviate period poverty for multiple populations, including Medicaid recipients, people experiencing homelessness, students in all learning environments (elementary and secondary schools, as well as colleges and universities), and incarcerated individuals, including those held in federal detention.

Most importantly, we need to act locally.

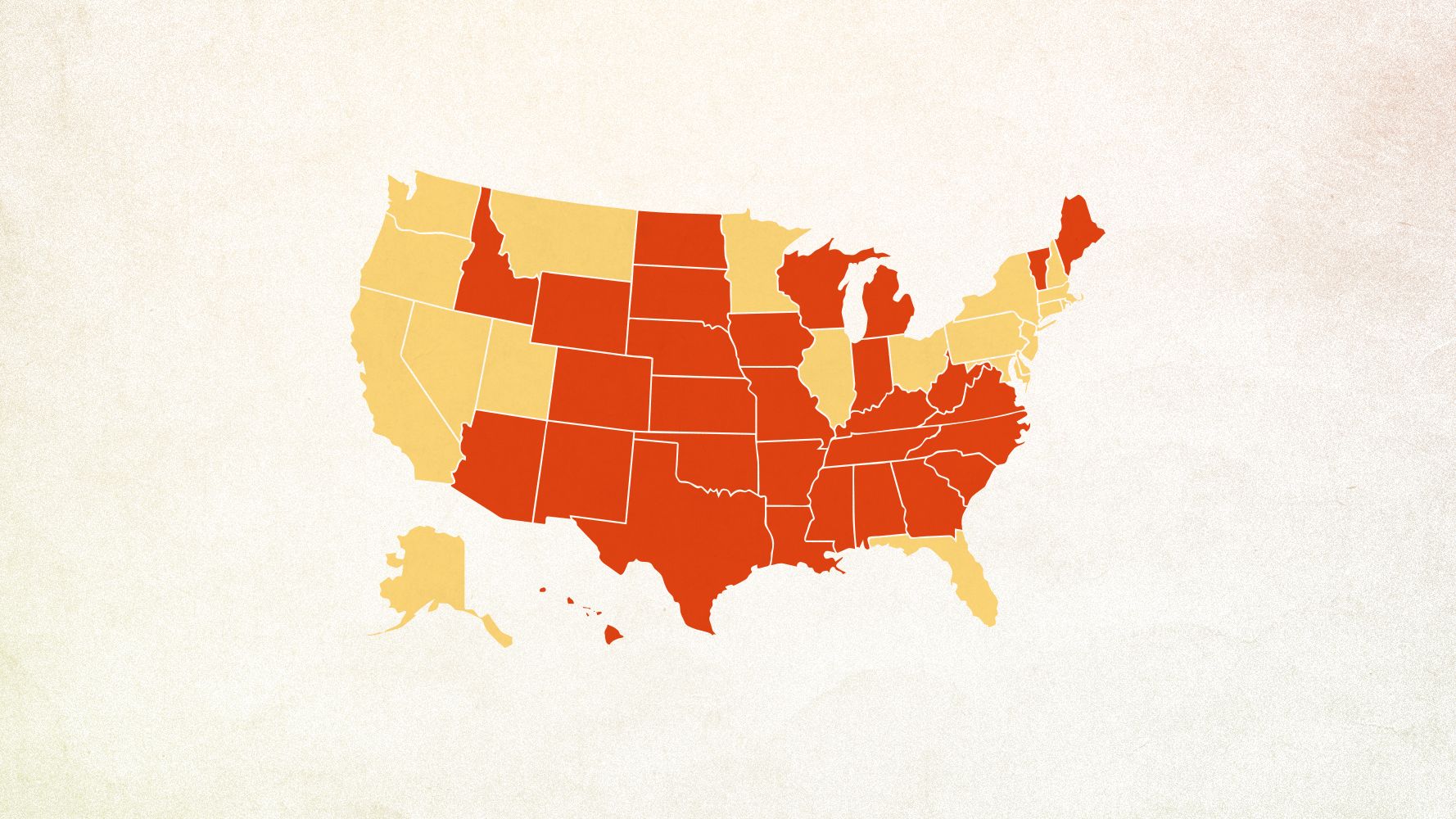

Diamant references the fight to take down the “tampon tax”—one that must be fought state by state, given that’s where sales tax is levied (and sometimes by municipalities and counties, too). Here in the U.S., 30 states still fail to exempt menstrual products from sales tax, while collecting an estimated $125 million annually from our period purchases. (Click here to see where your state stands and how to take action.)

But countless other big changes can be made in our own communities as well. Consider raising the issue with your hometown officials and agencies; ask that they address menstrual needs in the facilities they oversee, whether it be a library, a recreation center, or a food drive. Part of acting locally, as Diamant reminds us, is simply raising our voices. Write op-eds and letters to your local newspaper. Write to your representatives. Push back against period shaming and online bullies. Make it safe for everyone to speak their truth.

The louder and prouder we all are about claiming these stories and connecting them to our advocacy and activism, the harder this issue will be to ignore and the further we’ll go toward eradicating stigma, passing better laws, and ensuring a world where menstrual equity reigns for all. Period. End of sentence.

RELATED STORIES

Jennifer Weiss-Wolf is the cofounder of Period Equity and a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law. She is the author of Periods Gone Public: Taking a Stand for Menstrual Equity.