This Juneteenth, Black Liberation Requires Action

Boston mayoral candidate Andrea Campbell lost her twin brother to death in prison. This year, on Juneteenth, she's reflecting on the racist systems that resulted in their two very different life stories.

Celebrating Juneteenth with my family in Roxbury, a historically Black neighborhood in Boston, is a memory I treasure. It stands out among memories of a childhood filled with instability, loss, and struggle. Juneteenth was (and still is) one big block party—Roxbury Homecoming—where folks from every neighborhood and relatives from out of town would gather in our local park for food, music, and connection. Juneteenth commemorates the day formerly enslaved Black people learned they were free and celebrated their newfound liberation. After this last year, I find myself reflecting on and thinking about what the next wave of liberation for Black people should look like. For as far as Black people have come, we still have a long way to go.

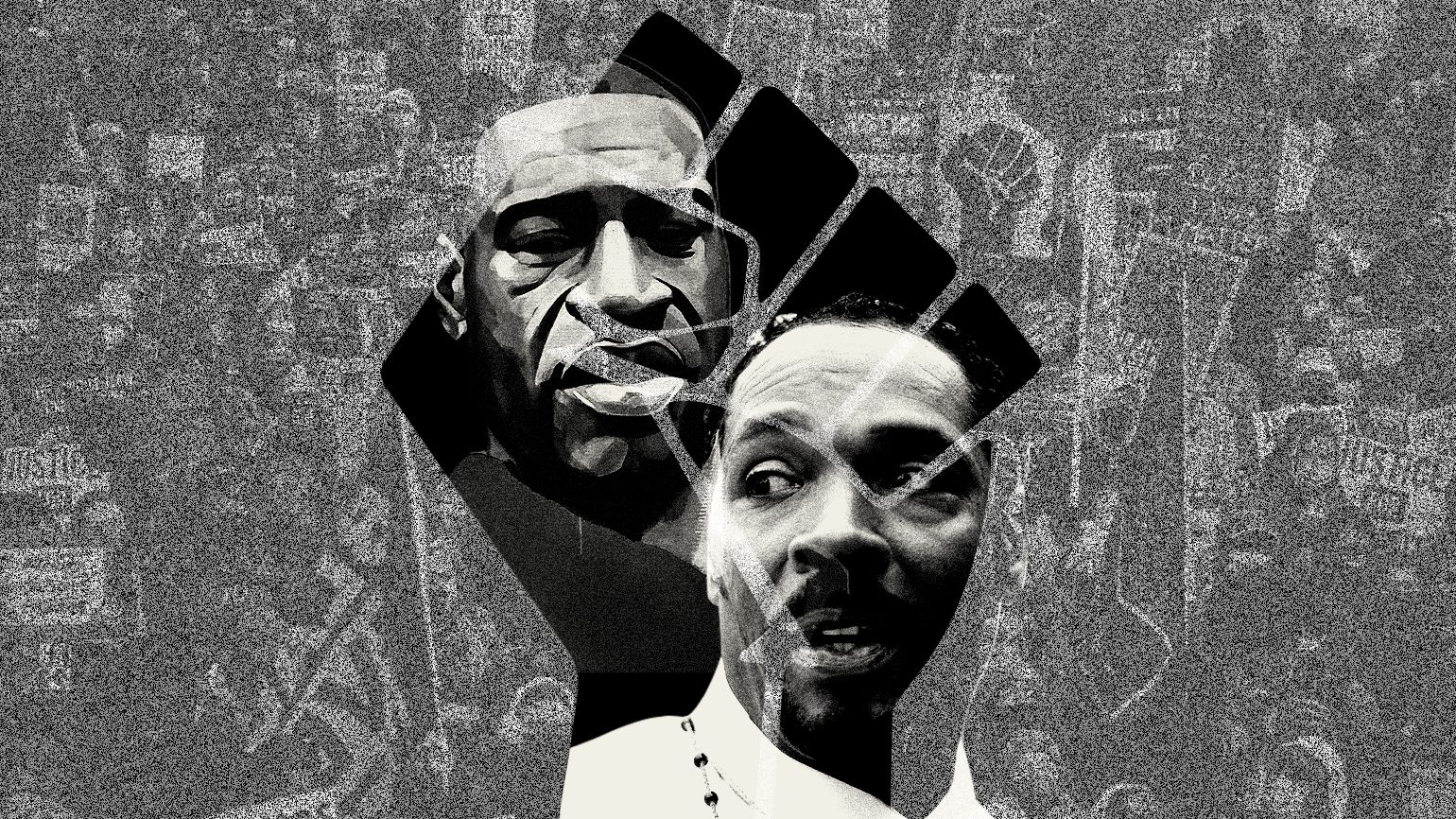

Black families still have less wealth than white families. Black unemployment regardless of education is still twice that of white unemployment. A little more than a year has passed since George Floyd’s murder, and Black lives are still being lost to police violence and an unjust criminal legal system: Black people are three times as likely to be killed by police and five times more likely to be incarcerated than white people. Personally, I’ve been thinking about 16-year-old Ma’Khia Bryant whose life came to a tragic end after being shot by a police officer responding to her sister’s call for help. Despite tremendous insecurity and trauma, moving between homes with relatives and the foster system, Ma’Khia remained a good student and sister.

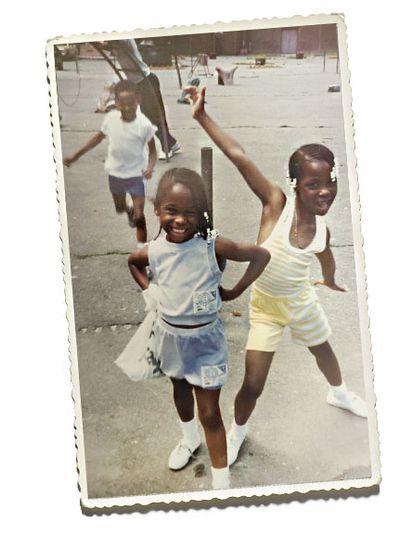

The author and her twin brother, Andre.

Ma’Khia’s story resonates with me because my brothers and I grew up in public housing, often on food stamps, and were shuttled between foster homes and extended family. This instability would start when I was only eight months old after my mother died in a car crash while on her way to visit my father, who was in prison and would remain so for the first eight years of my life. Every day I think about how many Black girls and boys are growing up like we did, with families impacted by incarceration and loss, in and out of foster care. These are, sadly, generational cycles of poverty and trauma perpetuated by systemic inequity.

Foster children face a disproportionate risk of being incarcerated. One quarter of foster care alumni will become involved with the criminal legal system within two years of leaving care. And if you are a Black youth in foster care? Your situation is compounded by the fact that Black youth are subject to disproportionate rates of school discipline and criminalization: Black students make up 15 percent of the nationwide K–12 student population but constitute 31 percent of all referrals to law enforcement and 26 percent of all school-based arrests. Several studies have shown that Black youth are four times more likely to be suspended from school than their white counterparts. As a result of these suspensions Black youth are more likely to fall behind and not graduate high school, growing their chance of incarceration, also known as the school to prison pipeline.

The author at a campaign event.

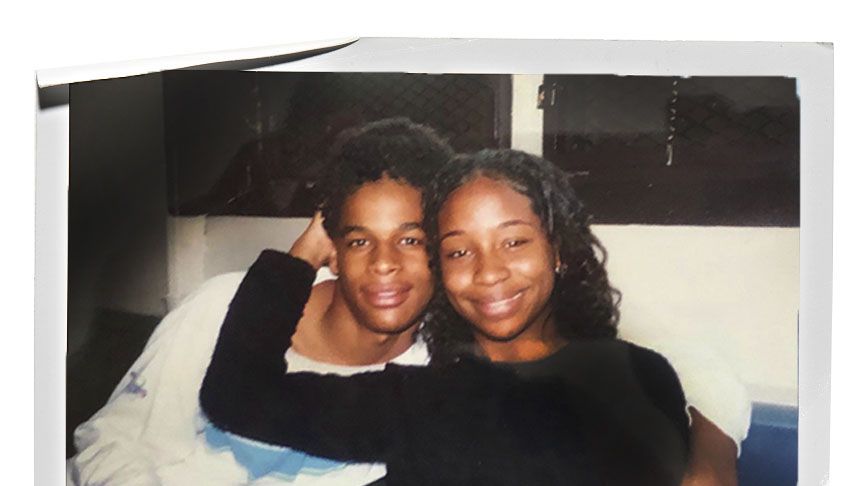

By the grace of God and the opportunities my city and Boston Public Schools afforded me to overcome long odds, I am here, now in my third term on the Boston City Council and running to be the first Black woman elected mayor of Boston. But my twin brother Andre is not—he died nine years ago as a pre-trial detainee in the custody of the Department of Corrections at only 29 years old.

For me, the work of being a public servant has always been driven by one question: How do twins born and raised in the same city have such different life outcomes? The work has always been about breaking cycles of trauma, poverty, criminalization, and inequity—cycles that are generational for Black people in this country. My brother Andre was funny, compassionate, sensitive, and incredibly smart. We were inseparable—until our paths diverged in school. While we both struggled with childhood instability and trauma, I was provided with mentorship and guidance, even love, in moments of struggle, whereas Andre—like many Black boys—was not; he was over-disciplined and often removed from school with his peers due to ‘behavioral issues.’ I was put on an advanced work track, gaining entry into Boston Latin School, a prestigious high school that helped me earn admission to Princeton University and eventually UCLA Law School. Andre would graduate from a high school with far less resources and opportunities. He cycled in and out of the criminal legal system, never quite finding his footing, before ultimately dying in a state prison after not receiving adequate healthcare for his scleroderma.

Andrea and Andre around age 15.

Now as a mom, I look at my two young Black boys—ages 18 months and 3 years—and want them to be afforded every opportunity. More so, I want their humanity to be valued. To make that a reality, we need systemic reform and leaders who understand these disparities first-hand. Boston is a reflection of the country, with a shocking racial wealth gap—one where white families have a median net worth of a quarter million dollars while Black families have a median net worth of $8. In Boston, in one year, Black residents accounted for 70 percent of stop and frisk incidents even though we make up just a quarter of the city’s population. Half of Boston Public School students don’t graduate college. When the ancestors celebrated that first Juneteenth, I know they hoped for better outcomes and brighter futures for themselves and their families, but instead many were greeted with intentionally racist and exclusionary policies whose effects are still felt by Black families today.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Since being elected in 2015, I’ve used my lived experience to create policies that confront these inequities and drive systemic change. I have spearheaded legislation that has created more affordable housing and economic wealth for residents; established systems of accountability and civilian oversight for our police department; successfully advocated for our city’s investment in youth jobs and youth development programs to break cycles of criminalization; and fought to reallocate money out of policing and into community-based programs and other strategies that address the root causes of violence.

The author speaking with supporters.

A mayor has the power to change a lot with the swipe of her pen. We need executives who will use that power to truly and finally eradicate the systemic and racial inequities that I and Black people all across this country have known and lived for generations. So we can indeed be free. Cycles of violence and criminalization in communities of color are interrupted by building wealth and ownership, and expanding access to excellent education, good jobs, affordable housing, mental health services, addiction treatment, youth programs and jobs, and community-based violence prevention and intervention programs and initiatives. Cycles of criminalization that begin in our schools can be disrupted by removing School Resource Officers, which studies show compound the existing over-disciplining of Black and brown children, and implementing a restorative justice approach by hiring more school counselors, mental health clinicians, and social workers.

If just some of these initiatives had been made available to Andre, he might very well be alive today, watching my boys grow up or raising a family of his own. This Juneteenth, we need to not only celebrate emancipation, but more so to think and lead boldly on the next steps for racial justice and liberation. We must break cycles of poverty, trauma, criminalization, and generational inequity so that we don’t see more young Black lives cut short like those of Ma’Khia and Andre.

Andrea Campbell is Boston City Councilor for District 4 and a candidate for Mayor of Boston.

RELATED STORIES