Imagine your phone is hacked and your very personal information is stolen: phone numbers, pictures, emails, everything. You are now being blackmailed by the hacker. The request? That you send sexual pictures of yourself or engage in sexual acts on video. Fail to comply and your sensitive information or photos will be exposed to your family, friends, and colleagues.

This nightmare scenario is one faced by hundreds of people across the United States every single day—and there are currently no laws protecting them.

Welcome to the growing pheonomon of "sextortion," a widespread form of corruption in which sex—not money—is the currency of the bribe. Employers, teachers, public officials, and ordinary citizens are blackmailing victims to have sex with them or send them pornographic images in exchange for the protection of their own information. Think of this as the next step in the phone-hacking sex crimes perpetuated against female celebrities like Jennifer Lawrence—only they can happen to anyone.

When she did not comply with the hacker's demands for more sexual content, her photos were distributed to hundreds of pornographic sites with her identity included.

Women, girls, and teenagers are the ones most at risk. Using false identities, online predators manipulate them to share private information and images. And so begins the vicious cycle: once these images are obtained, more and more are demanded. The victims cannot escape.

And perpetrators could be anyone. Earlier this year, Michael C. Ford, a former U.S. State Department employee, was sentenced to five years in a federal prison for using his computer at the American Embassy in London to hack into the online accounts of young women and search for sexually explicit content. He would then steal these images and blackmail his victims. Ford targeted hundreds of women, some as young as 18, and was ready to ruin their lives. He threatened to send their intimate photos and videos to family members or post them online—names and addresses included—if the women didn't make sexually explicit videos specifically for him.

A victim of a different sextortion crime, identified as Elizabeth, had nude images stolen from her email. When she did not comply with the hacker's demands for more sexual content, her photos were distributed to hundreds of pornographic sites with her identity included. She has been harassed and stalked since then, and says the shame and lack of control has at times taken over her life.

Victims of sextortion often suffer like Elizabeth—enduring devastating and long-lasting harm because the psychological (and reputation) damage is felt long after the initial crime. They live in constant fear that the images may show up at any time, or anywhere. Yet, victims fear that reporting the crime will only lead to more embarrassment, so they generally don't seek help.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

According to a new TrustLaw report from the Thomson Reuters Foundation, produced by the law firm Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe, most acts of sextortion go unnoticed, unreported, and unpunished.

In the case of Ford, he was indeed charged, but only with computer hacking and cyberstalking. He did not face charges of extortion for sex or sexual images, because such specific laws do not exist.

The person who stole Elizabeth's photos was never prosecuted at all.

Despite increased recognition from law enforcement agencies that sextortion exists—and that it is indeed on the rise—the United States currently lacks adequate legal solutions to tackle the scope of this crime. While technology has radically transformed the way we connect, interact, share, and access information, the law has not been updated to address this fast-growing reality, leaving victims powerless and predators loose on the prowl.

most acts of sextortion go unnoticed, unreported, and unpunished.

Progress starts with reframing this type of blackmail as illegal. The TrustLaw report, produced for Legal Momentum, America's oldest legal advocacy group for women, calls for the recognition of sextortion as a specific and growing sex crime—and for the adoption of appropriate legal measures to fight it across the United States.

In many cases, small modifications to existing laws could incorporate the definition of sextortion, protecting thousands of would-be victims. (For example, one very simple amendment could be made by adding "sex or sexual images" to the list of "things of value" that cannot be demanded through force or threat.)

Sextortion is also getting visible political support. Earlier this year, Katherine Clark, a Democratic representative from Massachusetts, called for a new federal law criminalizing sextortion, and Barbara Boxer, a Democratic senator from California, has formally asked Attorney General Loretta Lynch for information on how the Justice Department collects data on sextortion cases.

But protecting victims who are being blackmailed into supplying sexual images of themselves shouldn't be a polarizing political issue. It is a common-sense reform that everyone should get behind in this dangerous new digital age.

Monique Villa is the CEO of the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

-

Emma Stone Says She Wants to Be Known By Her Birth Name from Now On—Not Emma, Her Stage Name

Emma Stone Says She Wants to Be Known By Her Birth Name from Now On—Not Emma, Her Stage Name“That would be so nice.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Anya Taylor-Joy's Chocolate Corset Gown Looks So Rich

Anya Taylor-Joy's Chocolate Corset Gown Looks So RichAnd those Tiffany jewels?!

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

The Best Spring Shoes Hiding in the Sale Section

The Best Spring Shoes Hiding in the Sale SectionThe perfect opportunity to step up your footwear game.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Documentaries About Black History to Educate Yourself With

Documentaries About Black History to Educate Yourself WithTake your allyship a step further.

By Bianca Rodriguez Published

-

48 Last-Minute Father's Day Gifts to Scoop Up

48 Last-Minute Father's Day Gifts to Scoop UpHe'll never even know you left it until now.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

16 Gifts Any Music Lover Will Be Obsessed With

16 Gifts Any Music Lover Will Be Obsessed WithAirPods beanies? Say less.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

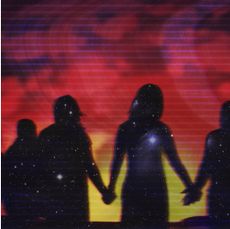

In 'We Are Not Like Them' Art Imitates Life—and (Hopefully) Vice Versa

In 'We Are Not Like Them' Art Imitates Life—and (Hopefully) Vice VersaRead an excerpt from the thought-provoking new book. Then, keep scrolling to discover how the authors, Jo Piazza and Christine Pride, navigated their own relationship while building a believable world for Riley and Jen—best friends, one Black, one white, dealing with the killing of an unarmed Black boy by a white police officer.

By Danielle McNally Published

-

This Pet Food Dispenser Is a Game-Changer for My Pet

This Pet Food Dispenser Is a Game-Changer for My PetThe futuristic-looking Petlibro Granary makes me feel so much less guilty being away from my dog.

By Cady Drell Published

-

Love Has Lost

Love Has LostQuasi-religious group Love Has Won claimed to offer wellness advice and self-care products, but what was actually being dished out by their late leader Amy Carlson Stroud—self-professed “Mother God”—was much darker. How our current conspiritualist culture is to blame.

By Virginia Pelley Published

-

What Does "ROC" Mean at the Tokyo Olympics?

What Does "ROC" Mean at the Tokyo Olympics?It's a temporary workaround in the aftermath of Russia's massive doping scandal.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Trolls Thought I Was Anthony Weiner’s Cyber Mistress

Trolls Thought I Was Anthony Weiner’s Cyber MistressTen years later, I realize I shouldn’t have been ashamed.

By Megan Broussard Published