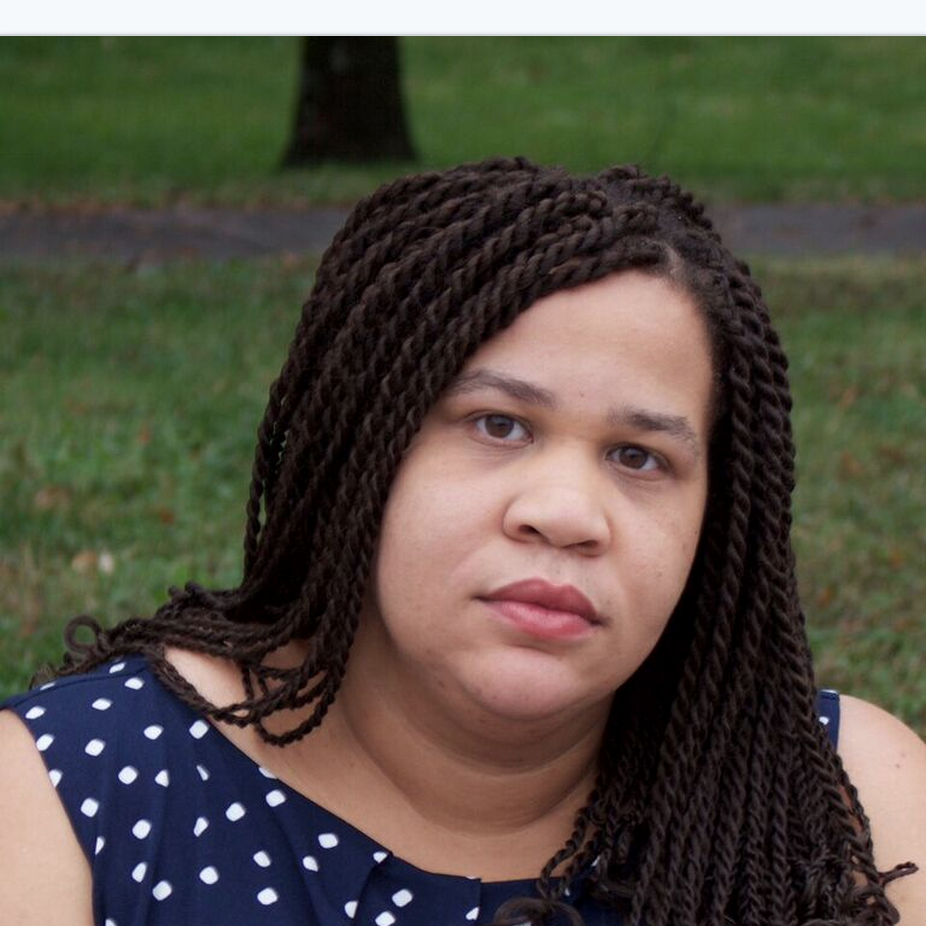

I'm a 29-year-old well educated African-American woman stuck in a depressive spiral. The challenges of paying for care–while anticipating racism and stigma– make finding someone to help me manage my mental health issues daunting at best, and hopeless at worst.

I can't see myself going through the series of micro-aggressions from therapists and other patients again.

A few things contribute to my mental health issues: upheavals at home, the death of a family member, and the unpredictability of my job (I'm barely making enough money to cover my basic bills). It all makes me dread opening my eyes when my alarm goes off in the morning.

I spent my work hours examining racial disparities and studying the legacy of slavery and segregation in America–and the awareness of being black in a world that necessitates a movement like #BlackLivesMatter is hard information to digest. I was always wondering what will happen next.

"My mom went so far as to call my disorder a 'white girl's problem.'"

I know that what I was feeling was more that just sadness or "winter blues." It was 77 degrees outside and I couldn't force myself to abandon the blank screen on my computer. I was physically, mentally, and emotionally burned out, so I knew it was time to seek help before things got worse. I know because I've been through this before.

I've grappled with the stigma and stereotypes around mental illness since I was 10 years old, when I began denying myself food because I didn't think I deserved it. My teacher told my parents, and they forced me to eat. At 12 I discovered bulimia, and by 15 I was self-injuring to mask all of the chaos that was going on at home–and in my brain.

My parents diminished the severity of my issues. My mom went so far as to call my disorder a "white girl's problem"—she said it was basically a luxury issue. I am the daughter of a farmer and an entrepreneur, and their day-to-day problem-solving skills are meant to handle issues like food, water, shelter, and money, so mental health just wasn't a tangible enough issue.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

At 16 I was sent to my first therapist—my high school threatened to expel me because they thought I was a danger to others as well as myself. Administrators made the rules clear: If I wanted to graduate from the prestigious arts boarding school I'd auditioned for, I was going to have to go to therapy.

I hated every moment I sat in my therapist's chair because I couldn't relate to this older white woman who found the hair growing from my head "interesting." When I came in with a different hairstyle, she spent half the session talking about how my hair made me feel. Once, she even touched my hair.

"I couldn't relate to this older white therapist who found the hair growing from my head 'interesting.'"

All of this occurred before the Information Age of the internet, so I couldn't turn to empathetic strangers on social media for support. And I was too ashamed to openly talk to my friends and family, who often downplayed my issue as a lack of self-control.

I tried therapy two more times in college, and finally found an African-American therapist who understood my worldview. While I made progress with him, he realized I needed acute around-the-clock care he couldn't provide.

My parents were forced to notice when the Ivy League university I attended sent me home on medical leave, with the requirement that I go to an eating disorder treatment facility and pursue therapy.

I found myself at a treatment center in Florida, where group therapy did more harm than good. In the group setting women questioned the veracity of my experiences surrounding race. I was often asked if I "remembered the situation correctly."

I was the sole African-American in a group of 15 Caucasian women, and in no uncertain terms I was told the racism I was feeling and talking about wasn't real. Apparently I dreamt up that scene where a group of white male teenagers repeatedly yelled the word "nigger" from their red sedan as I walked to my dorm from the library. My serious psychological distress was being downgraded yet again.

The anxiety from those flashbacks cause nightmares that can leave me breathless and tense.

"I was told the racism I was feeling and talking about wasn't real."

This only cements my need to find a therapist. But finding one who understands my reality—ideally an African-American therapist— in rural South Carolina feels impossible. According to a 2014 survey, African-Americans make up less than 2 percent percent of American Psychological Association members and many of them are located in major cities.

Still, I knew I had to put my past experiences with other mental health professionals aside and renew my desire to conquer my depression.

So, I've made another appointment. I know that a therapist won't be my savior, but hopefully she will remind me of the tools that I can utilize to help myself cope. It's the hope that keeps me going on the tough days, when my body feels not-quite-right and my mind refuses to respond to positive stimuli.

Right now hope is enough.

Follow Marie Claire on Instagram for the latest celeb news, pretty pics, funny stuff, and an insider POV.

Latria Graham is writer, editor and cultural critic currently living in Spartanburg. Her interests revolve around the dynamics of race, gender norms, class, nerd culture, and- yes, football. You can find out more about her here.

-

Zendaya's Method Dressing Marathon Is Over

Zendaya's Method Dressing Marathon Is OverShe found a new way to serve in custom Vera Wang.

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 Show

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 ShowModels at the Dior Fall 2024 show paired bitten lips with bare skin, a beauty trend that will take precedence this season.

By Deena Campbell Published

-

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget Dilemma

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget DilemmaSee every under-$300 spring item on my wish list.

By Natalie Gray Herder Published

-

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"Senator and breast cancer survivor Amy Klobuchar is encouraging women not to put off preventative care any longer.

By Senator Amy Klobuchar Published

-

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My Body

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My BodyI'm plus size, but after I decided to pose nude for photos, I suddenly felt more body positive.

By Kelly Burch Published

-

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?Much like abortion, surrogacy, and IVF, becoming an egg donor was a reproductive choice that felt unfit for society’s standards of womanhood.

By Lauryn Chamberlain Published

-

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in Check

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in CheckGut health = wealth.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo Olympics

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo OlympicsShe withdrew from the event due to a medical issue, according to USA Gymnastics.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Truth About Thigh Gaps

The Truth About Thigh GapsWe're going to need you to stop right there.

By Kenny Thapoung Published

-

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” Condition

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” ConditionDespite having no outward signs, they can be brutal on the body and the mind. Here’s how each woman deals with having illnesses others often don’t understand.

By Emily Shiffer Published

-

The High Price of Living With Chronic Pain

The High Price of Living With Chronic PainThree women open up about how their conditions impact their bodies—and their wallets.

By Alice Oglethorpe Published