Classes had already begun when the fire broke out at Intermediate School No. 31, an all-girls middle school in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, Islam's holiest city. As the flames and smoke spread, panicked students fled for the exits. Outside, firemen assembled quickly, preparing to pull the girls to safety. But they never did: Saudi Arabia's religious police stepped between the students and their rescuers, beating the girls — who were not wearing their head scarves or abayas — back into the inferno. On that day in March 2002, 15 schoolgirls were trampled or suffocated to death in what is perhaps the most dramatic recent example of the clash between religion and humanitarian aid. In many Islamic countries, custom dictates that a woman or girl cannot be viewed or touched by a man outside the immediate family, even it that man is a doctor — or a rescue worker trying to save her life. So in times of crisis, when a woman is alone and in need of serious help, there's only one place to turn. Another woman.

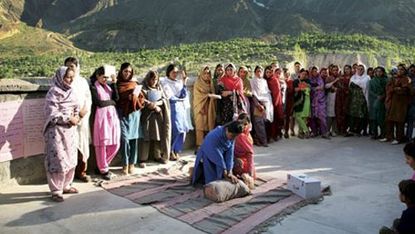

The Rescue Squad

Zeb Alam crouches on a tiny ledge several hundred feet above the ground. As she bandages the head of a wounded civilian on a basket stretcher, her bright orange pants and top flash brilliantly against the pewter-gray granite of the mountain face. On the far side of the steep gorge, her colleague Nasreen Fatima carefully checks that her climbing harness is securely fastened. Four months pregnant with her first child, Fatima's body is still reed-slim. Confident she is properly secured to the zip line she and her teammates have just rigged, Fatima steps out into the air and pulls herself over to Alam and the stretcher. Far below, boulders the size of cars litter the temporarily dried-up riverbed, a testament to the destructive flash floods that periodically sweep through the region.

After connecting the stretcher to the safety line, Fatima, 5'1", works her way back across the gorge. Meanwhile Alam, now on climbing ropes, begins rappelling down the rock face, carrying a child strapped to her back for safety. With her body perpendicular to the mountain, Alam appears to delicately walk down the sheer face. "If I move too fast when I'm rescuing someone this way," she explains, "I could start a rock fall, and that could kill both of us."

It's no secret that the terrain here, while stunningly beautiful, can quickly turn deadly. Northern Pakistan is home to five of the world's highest peaks, including the massive, snowcapped K2, which, at 28,250 feet, is dominated only by Mount Everest. In this region, three of the earth's greatest mountain ranges — the Himalayas, Karakoram Range, and Hindu Kush — originate, and the land is rarely still. Avalanches, landslides, tremors, and earthquakes are all a regular part of life.

At the bottom of the mountain, Alam and Fatima remove their climbing gear. The sense of urgency has dissipated, and the women eagerly rehash the details of their latest rescue mission. Fortunately, this has only been a training exercise: The child on Alam's back is a dummy made to weigh the same as an 8-year-old; the man in the stretcher is a community volunteer. But the dangers of mountain rescuing are real, and trial runs are vital to keeping the women's skills honed. Despite being unpaid volunteers, Alam and Fatima know they may be called upon at any moment, as they were in October 2005, when Pakistan was hit with the worst earthquake in its history.

Both Alam, 30, and Fatima, 35, are members of a search-and-rescue program for Focus Humanitarian Assistance, an emergency-response group affiliated with the Aga Khan Development Network, a group of international private agencies working to improve living conditions and opportunities in the developing world. In addition to earthquake victims, Alam and Fatima's team in Gilgit (a 15-hour drive from Pakistani capital, Islamabad) have also rescued victims of flash floods and mudslides. "Mudslides crush and suffocate — people rarely survive," says Alam, who was called to assist during one triggered by last summer's monsoon. "Houses were covered with 12 feet of mud."

Alam and her colleagues in Pakistan and Tajikistan are the first Muslim women in today's Islamic world to risk their lives this way to save others. "Our men can be very conservative," says Alam. "They won't let a man who is not a relative touch their women" — even if it means letting her die.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

That Pakistan has female search-and-rescue workers is in itself remarkable. This is a country, after all, in which arranged marriages, jail sentences for rape victims, honor killings, and dowry burnings (when a bride is burned to death by her husband if her dowry is not large enough) are common. In Baluchistan, one of the country's four provinces, many residents abide by the maxim that a woman should leave her home only three times in her life: when she is born, when she marries, and when she dies. In the fabled North-West Frontier Province, Taliban-style repression spilling over from neighboring Afghanistan is fast taking hold. Female shoppers at the local market are completely swathed in black, faces and hands covered despite the sweltering heat — a marked change from a few years ago, when women regularly wore tunics and loose pants in public.

So perhaps it isn't surprising that although female search-and-rescuers are equipped with orange jumpsuits like their make colleagues, many are reluctant to wear them, finding them too formfitting for religious reasons. They prefer instead traditional salwar kameezes with long dupatta shawls covering their heads and upper torsos. They compromise: After Fatima pulls the climbing harness over her jumpsuit (instantly outlining her hips, groin, and butt), she whips her dupatta off her head, tucks her hair into her mountaineering helmet, and ties the shawl around her lower body, this preserving Pakistani-style modesty.

Yet the female search-and-rescuers are no wilting flowers. In the mammoth earthquake last October, which killed an estimated 87,000 people — completely pancaking two cities and leaving some 3 million homeless — Alam and Fatima were among the first to be helicoptered in to help. Of course, they needed their husbands' formal permission to go. Even one night spent away from home by a woman was previously unheard of in these parts, where adult females are expected to travel with a male family member at all times.

Alam wondered how her husband would respond to her request to join the search-and-rescue program. Like many girls, Alam was removed from school and educated by a private tutor once she hit 15. At 19, her family gave her away in an arranged marriage, and her husband's family did not permit her to attend college. "Our culture would prefer we stay at home, but Mir was very supportive when I asked him about joining the search-and-rescue team," she says. "He knew I'd have wanted to be a social worker, if I'd been able to go to college. He's a policeman, so he also knows how important this work is in our mountains. But some of my friends tried to discourage me, saying I wasn't 'normal.'"

"People have criticized us. They say this is not women's work, that it isn't suitable for us," adds Fatima. "But I tell them we are serving humanity. I ask, 'If your relatives were injured, wouldn't you be glad that I do this?' Yes, I know that we will not change society so quickly."

Last year's quake, which measured 7.6 on the Richter scale, was the largest natural disaster ever to befall Pakistan. Communications in the region were initially wiped out, and in the chaos of the first day, it wasn't immediately known how many villages in the mountainous region were affected. Instead, Alam and Fatima's team flocked to Islamabad, where a luxury high-rise apartment tower had collapsed. The rest of the capital's eight embassies, expensive homes, and streets were largely untouched. "I'd never been inside a high-rise," confesses Alam. "Adults and children were buried under great slabs of rubble of what had once been a 10-story building. People were amazed to see female rescuer. They kept grabbing at us, sobbing, 'Rescue my mother first.' It was hard to ask them to be patient."

The shock of seeing the high-rise reduced to dust and debris is still fresh to Fatima. "No matter how much you train, until you see what happens in an earthquake this size, you have no idea of its power," she admits. "I was really scared until I started helping. Then, that's all you think of. All day long, we were removing the injured and dead."

As the enormity of the disaster became clear, the United Nations ordered the search-and-rescue teams north to the hardest-hit areas. Flying low in a helicopter over Muzaffarabad, a formerly vibrant city of 100,000 people, they could see giant slabs of debris lying in heaping piles, the remains of office buildings. "It was like the Day of Judgment," says Fatima. "All the buildings, every house — destroyed. I don't have words to describe it. I could only think, This disaster is too big. How can we handle it? But once we landed, I knew that no matter what capacity we had, we could save lives. God gave me the courage to handle whatever we faced."

Courage, yes — and stamina: All female rescuers undergo an intensive, three-month initial training program, followed by grueling monthly sessions to ensure they're able to maintain mental clarity under the most stressful conditions. Though a small group, the 18 women of Focus Humanitarian Assistance in Pakistan and Tajikistan have participated in multiple rescues.

Zafar Jang, a former army officer who helps train the community in disaster risk management, says the program looks for women who are athletic and can cope with high altitudes. "It's a risky, difficult job — bringing an injured person down from the top of a mountain," he says. "We prefer women who are older than 24 — so they are mature enough to make wise decisions in a crisis — but younger than 40, when they may have five or six children and no time to train or volunteer." And it goes without saying, having a liberal-minded husband is key: "Can she get her family's permission to do this work? Some communities won't let women leave their villages."

Of course, this line of work is not without challenges for a Muslim woman: Helping another woman is one thing, but Alam admits that the idea of administering CPR to a male victim is unnerving. "It would be hard for me," she says shyly. "But if there were no one else available, I would do it. It would be easier if the victim were a boy, though. My culture doesn't want me to touch a strange adult man."

Fatima, a former elementary-school math teacher, is more pragmatic. "Initially, we found it difficult to work with men," she confesses. "But we received encouragement, and it became less of a problem with time. Besides, the Koran says that when you save one life, it's the same as saving the world."

And the rewards for such heroic acts are personal, too: "There was such a sense of freedom at the beginning, when I rappelled off a mountain on ropes," says Alam. "It felt like flying. For the first time, I felt independent. Then I saw my mother-in-law was clapping for me. She told everyone, 'My son's wife is very different from other women. She is very brave.' I felt so proud to be able to do this work, to know I can save lives."

-

Charli D'Amelio Says Kim Kardashian "Inspired" Her to Work on Prison Reform

Charli D'Amelio Says Kim Kardashian "Inspired" Her to Work on Prison ReformThe social media star has partnered with REFORM Alliance.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Henry Cavill and His Girlfriend Natalie Viscuso Are Expecting Their First Child

Henry Cavill and His Girlfriend Natalie Viscuso Are Expecting Their First ChildCongratulations are in order!

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Katy Perry's Top Almost Came All the Way Off on 'American Idol'

Katy Perry's Top Almost Came All the Way Off on 'American Idol'LOL.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

How the Caregiver Crisis Is Preventing Us from Fixing the Pay Gap

How the Caregiver Crisis Is Preventing Us from Fixing the Pay GapWomen hold two-thirds of the jobs in the lowest paying fields—and it's keeping us down.

By Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka Published

-

14 Things Women Couldn't Do 94 Years Ago

14 Things Women Couldn't Do 94 Years AgoIn honor of the 19th Amendment, ratified 96 years ago today!

By Diana Pearl Published

-

Racist Photo Sent in Wake of Sorority Rush at University of Alabama

Racist Photo Sent in Wake of Sorority Rush at University of AlabamaUniversity of Alabama and national chapter of the sorority in question are investigating image captured from social networking site.

By Kayla Webley Adler Published

-

This Act Could Put an End to Anti-Abortion Legislation

This Act Could Put an End to Anti-Abortion LegislationWomen's right to choose is constantly at stake—but this might the solution.

By Diana Pearl Published

-

Yet Another Blow to Birth Control Coverage

The Supreme Court's latest decision will limit a key benefit for women.

By Laura Cohen Published

-

California Audit Finds Universities Are Failing Students Who Are Sexually Assaulted

California Audit Finds Universities Are Failing Students Who Are Sexually AssaultedState auditor report says colleges must do more to prevent, respond to, and resolve incidents of rape and sexual assault on campus.

By Kayla Webley Adler Published

-

The Most Ridiculous Sexist Laws Across the Globe

The Most Ridiculous Sexist Laws Across the GlobeWe're not kidding with these.

By Diana Pearl Published

-

Sexual Assault Survivors Speak Out Against Campus Rape

Sexual Assault Survivors Speak Out Against Campus Rape"This is the civil rights movement of our generation"

By Allison Ellis Published