'The Hate U Give’ Is the Movie Version of Growing Up Black in America

It makes the political very personal.

“When I was twelve, my parents had two talks with me. One was the usual birds and bees... The other talk was about what to do if a cop stopped me.”

It’s that second talk that Starr Carter, the 16-year-old protagonist in the book The Hate U Give, mentions that has become a rite of passage for nearly all Black children in America—including me. The novel, written by Angie Thomas, contains a familiar narrative, one that allows people of color to laugh, grieve, and process the Black experience in the U.S.

For Starr, that experience includes witnessing the fatal shooting of her friend Khalil at the hands of a white police officer. The storyline echoes the protest cries for Freddie Grey, Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, Sandra Bland...the list continues.

The highly-anticipated film adaptation of Thomas’s book, which premieres this Friday, pulls these cries off the pages—off the streets of Ferguson, Baltimore, and Minnesota, off the football fields—and puts them onto the screen. It’s a heavy and complex narrative masked in the vernacular of a teenage girl from the fictional Garden Heights. But I’d caution not to underestimate Starr (here played by Amandla Stenberg), through whose eyes and voice the story is told. Her story is my own, my friends’, my relatives’, your friends’—and maybe even yours. It’s the story of Black America.

If you haven’t read the book, there are a lot of details and references that could potentially be overlooked when viewing the movie. Here are three things you need to know about the adaptation of The Hate U Give before you see it (and you should see it).

The title is more than just a nod to rapper Tupac Shakur.

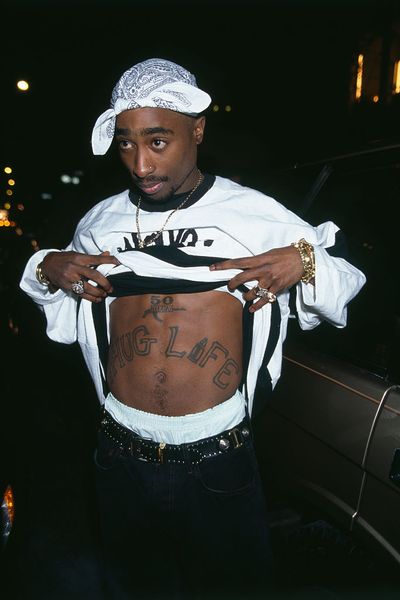

It’s a critique of our society’s current state. “The Hate U Give” is short for “The Hate You Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody.” Or, as Tupac’s stomach tattoo spelled out, “THUG LIFE.”

Tupac Shakur's tattoo.'

It’s the notion that whatever negativity, racism, or injustice you expose children to can impact and ruin future lives. As Thomas explained in an interview with Cosmopolitan, “When these unarmed black people lose their lives, the hate they've been given screws us all. We see it in the form of anger and we see it in the form of riots.”

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

You don’t have to look hard to see it in politics and the workplace and the news—the ways that hate passed down from generations before ours still lingers and continues to pollute the relationships we have with one another. The Hate U Give makes that hard to dismiss. Because there, wrapped in the lightning-quick dialogue and therapeutic quips that make the story’s tragedy more bearable, is the undeniable truth that our society needs to do better.

The ideologies of Black activists, like W.E.B. Dubois, are prevalent.

Starr likes to say she lives in two worlds. The first is the one she grew up in: the neighborhood of Garden Heights. In this world she’s Starr, the daughter of a nurse and a well-respected former gang leader-turned-grocery store owner. But she’s also the somewhat uppity Black girl who traded in her hoodie for a private school blazer. She’s mastered the ability to code switch because in the affluent and predominantly white environment of Williamson Prep, she can’t give anyone a reason to call her ghetto. At Williamson she’s the “cool” kind of black—her prep school uniform complemented by a spotless pair of Jordans and playlist that includes as much Taylor Swift as N.W.A.

Stenberg and Algee Smith as Khalil'

The pressure that Starr feels to maintain both versions of herself—Starr and Starr 2.0—is what Dubois would refer to as “double consciousness.” It’s the psychological notion that you cannot be Black and have just one identity, but rather that identity must be divided into various parts and versions of yourself.

Although developed in 1903, the notion of double consciousness isn’t unfamiliar to me or other Black people in America today. It’s a notion I’ve often felt pressured to subscribe to. Like Starr (and Thomas), I grew up in a middle-ish class household, with a scholarship that allowed me to attend a private school far above my family’s means, though not above the means of my classmates’ (I’m talking the Tony Hawk-level skate ramps in their backyards kind of affluent). I mastered code-switching at a very young age—younger even than Starr.

It’s easy when placed in environments unlike your own to begin seeing yourself through other people’s eyes. It’s another facet of double consciousness. The Hate U Give is just as much a coming-of-age story as it is a protest novel. As the narrative evolves, Starr sheds her double consciousness for a version of herself that isn’t a version at all—just Starr, the girl who stands up for what’s right and just. The story encourages others to do the same.

Though a Black kid is killed by a white cop, the story is decidedly not anti-cop.

Let me repeat that: The story is NOT anti-cop.

There’s a scene in the novel where Ms. Ofrah, the leader of a black activist group, comes to the house to speak to Starr about testifying. She pulls out a photograph of the black hairbrush Khalil was reaching for the moment he was killed. “That’s the so-called gun,” Ms. Ofrah explains. It’s not a story about why the police are untrustworthy, but about the greater danger of making assumptions, suggesting unequivocally that all people are capable of making them, but that we owe it to each other to be self-critical when we do.

'KJ Apa and Stenberg'

The Washington Post documented 990 fatal shootings by police officers in 2015, 93 of which involved unarmed victims, and Black men accounted for about 40 percent of those. The Post reported that “the only thing that was significant in predicting whether someone shot and killed by police was unarmed was whether or not they were black.” Implicit bias isn’t made up, and sometimes assumptions get the best of us. A hairbrush is not a gun, as Starr says. Eric Garner’s cigarettes were not a gun. Trayvon Martin’s Skittles were not a gun. And Oscar Grant’s attitude was surely not a gun.

The Hate U Give asks us to be honest with ourselves about our own biases and the way we play into dangerous dynamics. But more importantly, it also gives people of color and the allies fighting beside us hope in knowing that the fight isn’t over.

“I’ll never forget, I’ll never give up. I’ll never be quiet,” Starr says in the closing line of the novel as her vow to Khalil—and the host of other Black bodies before him and those that will surely come after.

The Hate U Give premieres in select theaters on October 5 and nationwide on October 19.

Alexis Jones is an assistant editor at Women's Health where she writes across several verticals on WomensHealthmag.com, including life, health, sex and love, relationships and fitness, while also contributing to the print magazine. She has a master’s degree in journalism from Syracuse University, lives in Brooklyn, and proudly detests avocados.