Three Generations, Two Young Women, and One Incredible Story of Survival in WWII

A fateful act of heroism would tie together not only two men in a lasting, transatlantic friendship, but also two women—the granddaughters they did not live to see.

On an overcast evening last September, at a beachside hotel in Vigo, on Spain's northwest coast, I took my seat next to the bride at a dinner table reserved for her and her groom's closest family. The seat assignment was an honor, especially considering that Nathalie Madjar and I had met just once before, three months earlier.

After dinner and speeches, everyone gathered around a piano, and the groom, Florent, sang Elton John's "Your Song," dedicating it to Nathalie and me. I never imagined I could feel so connected to someone with whom I'd only ever spent half a day.

But had it not been for her family, I never would have been born.

A clipping of the newspaper story detailing Murray Simon and Jacques Madjar's unlikely friendship

In the middle of the night on May 6, 1944, my grandfather Murray Simon, a 23-year-old American bomber pilot, parachuted out of a flaming plane, shot down by Nazis over German-occupied France. It was his 12th and final mission during World War II.

Murray and his copilot, both lieutenants with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, the U.S. wartime espionage unit), were following orders to fly late, fly low, and remain in the cockpit. The six other crew members were preparing to drop ammunition and supplies into France to support the Resistance. As the story goes, they were to release 12 canisters of explosives into the French countryside, blowing up railroad tracks to thwart Nazi movement ahead of a secret operation in which Allied troops would fight Nazi soldiers on the beaches of Normandy. Their plane was flying at 5,500 feet when a German night fighter blasted them with 20mm flak guns, hitting the gas tank and setting the B-24 Liberator ablaze. After dumping the cargo and ordering the crew to bail, Murray was the last man to jump. He pulled his parachute's rip cord and landed in a tree. Farmers and Nazis in the rural village of Mably, jolted awake by the commotion, watched the plane come crashing down in the woods nearby.

Dr. Madjar sent a runner to deliver a coded message to the underground: He had the Allied pilot. Send help.

A 6'1" Jew wearing an American uniform, Murray hid in a drainage ditch as Third Reich troops went door-to-door in search of fallen enemies, all of whom survived the crash. He slept intermittently until daybreak, when an elderly French farmer passed by. Shhhh, Murray gestured to the villager, who had seen him but did not stop. Ten minutes later, though, the Frenchman returned to the ditch with Dr. Jacques Madjar, the town physician, who locals knew was involved in the French Resistance. A Bulgarian-born Jew posing as a Catholic, Dr. Madjar, 33, was on a motorcycle and carrying a potato sack.

"Pouvez-vous me cacher?" attempted Murray in bad French for "Will you hide me?" It was one of two French phrases he recalled being spelled out on his military-issued language card (the other was "Je suis américain").

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

"Do not be afraid," Dr. Madjar answered in English, one of six languages he spoke fluently. He handed my grandfather coveralls and a beret to change into and stuffed Murray's uniform into the potato sack before burying it in the ditch. He then brought Murray to his home—steps from a Nazi artillery factory—where he lived with his pregnant wife, Madeleine, and their 9-month-old daughter, Elisabeth. Food was rationed in the German-occupied region of Roanne, but the Madjars fed my grandpa their last two eggs. Dr. Madjar sent a runner (a fellow resident also secretly one of the Maquis, French Resistance fighters) to deliver a coded message to the underground: He had the Allied pilot. Send help.

By sundown, an escort had arrived to lead Murray through the back roads of Roanne on bicycles borrowed from the Madjars. Pedaling past German patrols, Murray tried to keep his feet out of view so no one would notice his khaki, smut-caked military boots. Twenty minutes after he left, two SS officers knocked on Dr. Madjar's door, demanding the whereabouts of the American airman, who had last been seen at a checkpoint near the Madjar home. Dr. Madjar told them he had no idea what they were talking about.

Murray was headed for an Allied safe house, where he would pick up fake papers and a new identity as a deaf-mute Frenchman named Maurice Simon. From there, he was on the run with another hero in the underground, an OSS Marine. They rode a train to Castelnaudary in the company of more German officers before stealing a Gestapo staff car and driving south through the countryside. Roadblocks and the price on each of their heads complicated the journey. They abandoned the car and spent two weeks trekking through the Pyrenees by foot as drug mules. Guided and fed by tobacco-smuggling gypsies, they'd struck a deal to each haul a 50-pound pack of tobacco across the border into neutral Spain, where they arrived safely on May 21, 1944. More than 400 miles from Dr. Madjar's home, Murray traveled to the British Consulate in Barcelona to seek help. After being quarantined and interrogated, he returned to his London OSS base on June 2, 1944.

Nearly a month after the U.S. secretary of war had declared him missing in action, Murray telegrammed his mother: "I AM WELL AND SAFE -- NO NEED FOR WORRY -- WRITE TO MY OLD ADDRESS."

D-Day was four days later.

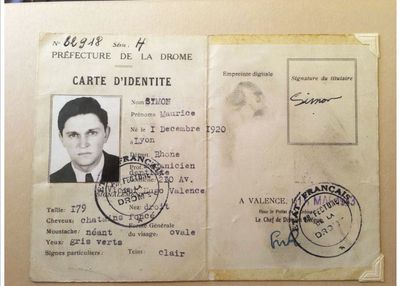

As part of his escape, Murray Simon was issued fake papers identifying him as a deaf-mute.

In June 1945, a year after arriving home at his mother's Queens, New York, doorstep, Murray opened his mailbox to find a handwritten letter from Dr. Madjar, along with a typed copy the U.S. military had translated into English. "My dear friend," it read. "You remember without a doubt this incident last year ... I would be very unhappy if any mishap came to you. I was able to learn in Paris, with considerable joy, from the Bureau of Reassignment ... that you went by plane to England. Today the liberation of our country is definitely realized. I can now write to you freely ... Someday you may take a trip to France ... Look for my home. It is open to you at any time. My little girl, whom you knew very well, has a little brother and is awaiting another in November. My wife joins me in wishing you well. A cordial handshake from an officer in the French Reserve."

It was the first of many overseas correspondences they would exchange in those first few years after the war, each one addressed to "My dear friend." Murray mailed the Madjars small gifts of chocolate, socks, and children's shoes— items that were in short supply in war-ravaged France. In one letter, Dr. Madjar shared that he had named Murray the godfather in absentia to the third of his five children. After a short-lived gig as a commercial pilot, Murray retired from the Air Force, married my grandma (who, like Dr. Madjar's wife, was named Madeleine), and moved to Philadelphia to start a tool business and a family.

In 1971, Murray and Madeleine visited the Madjars in France, their first reunion since the end of the war. When my grandparents stepped off the train at Roanne Station, Dr. Madjar and his wife were there to greet them on the familiar platform, smiling and waving the silk map Murray had left behind 27 years earlier. Together, they visited the ditch where they had first met. Over wine, Murray was presented with a piece of his plane, the cover of the loop antenna, that had been found on a nearby farm and held on to.

Over the years, the Madjar family visited my grandparents in the U.S. My mom recalls showing Dr. Madjar's son Moïse around Philadelphia when they were teenagers ("He was a very fast driver"). Meanwhile, my Uncle Doug attributes his fluency in French—dirty words and all—to the summer he spent living with Dr. Madjar and his family when he was 16.

During one of their reunions, Dr. Madjar and Murray, then middle-aged, shared their story with a Philadelphia newspaper. When Dr. Madjar spoke of how he was the youngest of eight siblings, all of whom had passed away, he added: "My brothers aren't all dead. This American pilot— he is my brother!"

I never met my Grandpa Murray—he died of lung cancer in 1981, months after walking my mom down the aisle—but the tales I grew up hearing sounded like the stuff of legends. During family gatherings, my brother and I would sit listening to Uncle Doug as he recounted the story of our war-hero grandfather and of the French doctor who saved him. Through a combination of my mom's superlative-laced descriptions of her dad (a "world-class pilot" or "hands down the very smart- est non-college-educated entrepreneur") and various relics scattered around our Massachusetts house, I developed a sense of wonderment about my grandfather's life.

There was a shoebox full of rusted war medals in my parents' linen closet, the basketball-size piece of Murray's plane that Dr. Madjar had gifted him stashed in our attic, and a Jewish history book with "To my dear friend Murray. —Jacques Madjar" scrawled in cursive on the table of contents.

There were also artifacts from Murray's postwar life as a tool salesman and importer. He had opened a warehouse in North Philadelphia, eventually developing an international manufacturing business that afforded him a lifestyle that included a winter condo in Florida and his own twin-engine Piper Navajo plane. I was 12 when my grandma passed away, and I remember my parents inheriting prototypes of a tool that Murray had patented, along with furniture and jewelry he'd brought back to the U.S. from business trips to Japan. Learning about Murray as a family man and a businessman only reinforced my admiration for Dr. Madjar, for it was because of him that my grandpa had the chance to meet his wife, start a business, and live to fly another plane.

We FaceTimed our parents, who crowded the phone from their homes in Boston and Lyon, crying and trying to process the sight of Jacques' and Murray's granddaughters together in the same frame.

As a New York City journalist building a career out of reporting human-interest stories, I was fascinated by this one. I'd study old photos of Murray through the years, trying to grasp fully how the son of a poor, widowed Russian immigrant working as a dental technician in Queens ended up flying clandestine night missions for the intelligence agency that was the predecessor to the CIA. There was also a certain mystique around the Madjars' existence, the result of some combination of the language barrier and ocean between our families, the decades that had elapsed since they'd last been in touch, and the miraculous circumstances through which we were connected. While I cherished the tales of the brotherhood between Murray and his savior, I'd resigned myself to thinking that "La Fabuleuse Histoire"—what our families have come to call the story—would remain a pieced-together oral history, a bedtime tale I'd share with my kids one day.

Then, last summer, as my husband and I were planning a vacation to Paris, I received a text from my mom (coincidentally on June 6, the anniversary of D-Day). She'd recently reconnected with Moïse, and she shared his daughter Nathalie's contact information—she was a screenwriter based in Paris—should I want to reach out. A few e-mails later, Nathalie and I arranged to meet for lunch.

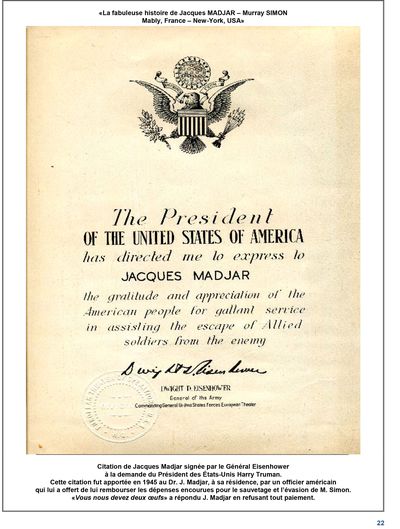

Then-General Dwight D. Eisenhower's commendation letter to Dr. Madjar

On a sunny Saturday in the country where our grandpas had first met, Nathalie and her then-fiancé, Florent, spotted me and my husband, Nate, at a booth in the back of a St.-Germain bistro. As we hugged and kissed hello, we held each other, overwhelmed with emotion. I felt like I was meeting a dear friend I'd known for many years but hadn't seen in a long time.

We spent the next three hours eating, drinking, and exchanging family stories. Like me, Nathalie had never met her war hero; Dr. Madjar had also died of cancer, a year after

Murray and nearly a decade before Nathalie and I were born. Nathalie and her two brothers had also grown up hearing about—and digging for more of—Jacques and Murray's fabulous history. In a frame atop their father's desk sits the citation sent by President Harry S. Truman and signed by then-General Dwight D. Eisenhower thanking Dr. Madjar for his gallant service assisting in the escape of an Allied soldier from the enemy during the war. It was a legend Nathalie could recite in French and English, and that she dreamed of one day turning into a screenplay. We FaceTimed our parents, who crowded the phone from their homes in Boston and Lyon, crying and trying to process the sight of Jacques' and Murray's granddaughters together in the same frame.

Picking up on the elation of the reunion, the waiter asked how we knew each other. We tried to explain our connection in a mix of French, English, and tears.

"No!?" he replied. "Extraordinaire!"

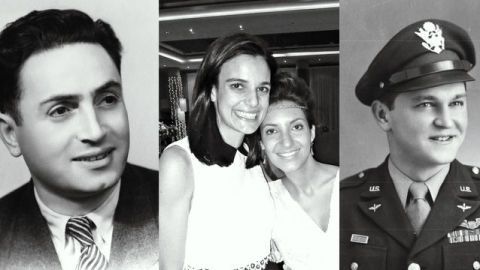

Nathalie Madjar (left) and the writer met up in Paris 72 years after Madjar's grandfather saved Sanders' grandfather's life.

We continued the afternoon traversing Paris and enjoying mille-feuille in the public gardens of the Palais Royal. It was joyous and hard to fathom: We're both writers living in beautiful cities, connected through two men with wives named Madeleine, big brains, Jewish roots, and one fateful act of heroism.

At Nathalie's wedding, I was introduced to one of her aunts, a 73-year-old retired math teacher with silver hair and an elegant neck scarf. She was Elisabeth, the 9-month-old baby my grandpa met the day the Madjars entered his life. As we danced to a mariachi band, I took Elisabeth's hand and felt a closeness I'll hold on to forever. She was there that day when Dr. Jacques Madjar saved Murray Simon's life, beginning a story that lives on in my dear friend Nathalie and me.

This article appears in the June issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.

Dedicated to women of power, purpose, and style, Marie Claire is committed to celebrating the richness and scope of women's lives. Reaching millions of women every month, Marie Claire is an internationally recognized destination for celebrity news, fashion trends, beauty recommendations, and renowned investigative packages.