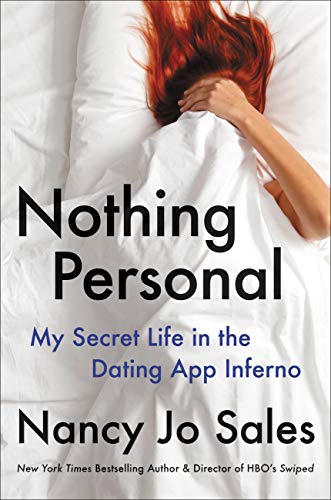

Nancy Jo Sales Wants Women to Know It’s Not You, It’s Dating Apps

The writer went viral for trashing Tinder in Vanity Fair. Her new book, Nothing Personal, pulls the curtain on online dating back even further.

Writer Nancy Jo Sales has a sort of double life: She is a reporter on what a sinkhole of misogynistic mindfuckery dating apps are; in 2015, her story “Tinder and the Dawn of the ‘Dating Apocalypse’” went viral, sounding the death knell for romance in the age of dating apps. At the same time, she started using them to answer the question of why she was almost 50 and alone. In her new memoir, Nothing Personal: My Secret Life in the Dating App Inferno, Sales hilariously and poignantly opens up about dating young(er) men, sending (or being sent) nudes, how dating apps reinforce the sexual oppression of women, and what it’s like to be both hailed as sex positive and slut-shamed. She spoke with Marie Claire about what all women can take away from her (mostly terrible) experiences.

Nancy Jo Sales

Marie Claire: You started using dating apps when you were 49, but in reading the book I see that your younger female friends were the ones who gave you the most usable, good advice for your dating journey. Who should read it?

Nancy Jo Sales: I wrote this book for anybody who dates, really, but I wrote it because of and for younger women. The reason for it is that even though anybody who is that age—twentysomething, thirtysomething, including a lot of my friends and sources that I interviewed for articles or for my film [Swiped on HBO]—even though they all know dating apps suck, it’s still not something that is talked about in mainstream media. Even in this moment, when we’re experiencing tech-lash, as they call it, where people are dumping on Facebook (rightly so) and Mark Zuckerberg is being hauled in front of Congress and finally we’re having real scrutiny of what tech companies like Google, Apple, and Facebook are doing to our world. Dating apps—this is an important point that I try to make in the book—have somehow escaped this scrutiny or criticism. When I’ve come out and criticized them, I’ve been attacked, by Tinder notably.

I wrote articles about this stuff. I interviewed people. I made a film about it. Meanwhile, I was using [the dating apps], so I really knew from personal experience what all this is about. But still, when my Tinder article came out in 2015, Salon said, “Oh, she just doesn’t get it because she’s old.” The Washington Post said I was naive. Slate called my distaste for Tinder a “moral panic.”

The reason I wrote the book is actually because I connected with [young women] about using dating apps at my local pub in the [New York City’s] East Village. I go there, and I’m talking to everybody about this stuff. All these women are telling me, like, “Oh, my God. I’m so glad you said that,” and “This is so true.” Or I’d be on a podcast about it and they’d say, “No one is saying this. Why is no one saying this?” Online dating is not fun. It’s dick pics. It’s harassing messages. It’s nonconsensually shared nudes. It’s objectification. It’s having weird dates. It’s having guys want to just jerk off to you. It’s talking to a guy and realizing he’s talking to three other women at once. It’s bad dates where they just want to have sex right away. No one is saying that, because if you don’t like it, you’re not a cool girl or something. But that’s just wrong. We like to think that we progress and that feminism progresses, but there’s a lot of things about this that are the worst dating has been.

MC: It sounds like the Wild West.

NJS: It’s the worst time to date in my lifetime. I’ve been married and had a few relationships; I was “real married” once and “fake married” once. [The guy was still married to someone else. It’s in the book.] And I’ve had lots of boyfriends, but I’ve mostly been single for my whole life. I just wanted to share my own experiences with younger women so they don’t feel alone. They don’t feel like this is okay. It’s not okay. Getting a dick pic is not okay, no matter how much people want to laugh and make a joke out of it. It’s aggressive. It’s assaultive. It’s actually a crime [in some places].

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MC: Did the book come out of the work you did on how the Internet and social media affect girls?

NJS: I’ve talked to hundreds and hundreds of women about online dating, of all ages, and the book starts with a woman my age because I wanted to show how it’s no longer just 24-year-olds who are using Tinder. It’s 64-year-olds.

MC: Who do you think has a thicker skin with it: you because you have more life experience, or younger women because they’re digital natives?

NJS: I don’t think anybody does or should have a thick skin about this. I think it’s abuse. I don’t think anybody should develop a tough skin about that, but what I do see is that, out of self-preservation, women say, like, “Oh, well, you know, I’ll just put up with this because this is the only way to date.” Sadly enough, it has become the only way to date, especially since the pandemic. Even before the pandemic, things were going that way.

My critique of all this is not a critique of the users. It’s a critique of the corporations that are exploiting users. They want our time, our money, and our data. They really don’t care if we ride off into the sunset with anybody. That’s not what they’re supposed to do. That’s not what we’re supposed to do.

The algorithms are just promoting you to continue to see the people who are already in the pool of your number of matches. It’s sort of like this elitist thing, and racist, where it’s promoting people of the same color, showing you people of the same color, and people who are matched on about as much as you are. It’s like this weird red velvet rope that the algorithms create.

I think the whole proposition is dehumanizing. I think it’s very concerning that corporate entities have overwhelmed our most private activity, which is not just dating but sex, relationships, intimacy. It’s disrupted, as they like to say, which is not always a good thing. They think it’s good, but it has disrupted the ways that we find intimacy in ways that are not actually intimate.

MC: Your perspective of the “before times” is probably useful.

NJS: Which was never perfect and not always great. I mean, as you read in the book, I got date-raped when I was 14 years old. I had terrible, terrible things happen to me. What I’m trying to say is I actually do think this is worse overall. We know that there are still problems with rape and sexual assault, sexual harassment in the workplace, domestic abuse. I don’t think that we’re suddenly in some promised land of feminism just because of MeToo, as important as it has been as a movement.

And dating apps are part of rape culture. The problem is that a lot of young women, in my experience as a reporter, feel that they’re not allowed to say that. They feel muted to criticize dating apps because that’s what everybody is using. The majority of people who use dating apps are not finding lasting relationships. So says the available data: Only 12 percent of American adults say they’ve ever had a relationship or a marriage through dating apps.

MC: You write that for online harassment, the laws haven’t caught up. But it sounds like the whole world hasn’t caught up to what’s possible via technology, whether it’s morals or etiquette.

NJS: The problem is that if you meet someone in person, we have evolved over tens of thousands of years on how to communicate in person. With online platforms, we don’t have the same ability to understand what others are saying, judge what the other person is like, or try and figure out if we can trust each other.

Also, screen time promotes aggressivity. I don’t have to keep telling you, “Well, the studies say…” but it is true that studies say that when you communicate over a screen, whether it’s on Instagram or Twitter (Twitter’s the big one where we see it), but also on dating apps, there is a tendency to be more aggressive.

Now, when you have men—straight men, I’m talking about, because that’s mainly my experience; you’re talking to straight men in the patriarchy, in misogyny, over a screen, which they have been led to believe through marketing is going to get them sex from you—they are not likely to necessarily see you as a full human being. Especially with the fact that the app provides them with pictures of you that they can put their finger on and judge one way or another: yes or no.

A lot of the so-called dating isn’t even dating as we even think of it anymore. It’s not like back in the day.... Again, I’m not so naive as to think that everything was great back then. But we did go on dates, right? We did make appointments to see each other and talk to each other and just have fun. Maybe we can go dancing, have a conversation. It didn’t necessarily mean you were going to get married or anything, but…the point of the whole date was to get to know each other.

MC: You quote some of the women saying, “I just want to do what I have to do to get out of there,” like they are willing to hook up if it means ending an awkward situation.

NJS: “I’ll do whatever—if it’s not too damaging to my psyche—just to get out of there.” But they’re being told what’s not damaging to their psyche or that it shouldn’t be damaging to their psyche. But it always is.

Two things about that. Number one, what you just said: How does it surprise anybody that women are not so excited about having sex with men right now when it’s all like dating-app hook-up sex? It’s like boom, boom, boom. It’s all influenced by porn.

You know, [men are] so uneducated. It’s also not their fault. These [dating apps] are corporations. These are dating apps designed by bros who just want to make money and brag about women they call “Tindersluts” or “Tinderellas.”

The reason it’s a memoir that goes back all the way to my childhood is because, as I started to think about all this, I realized that it’s all connected. Getting a harassing message from some dude on Tinder that says, “You look like you want to get raped”—there’s a direct through line from that to actually being raped as a 14-year-old to getting sexually harassed at work in the ’90s or catcalled on the street. I started to, as an older person, [think of] all the ways that I pushed this down, because we weren’t allowed to talk about this stuff.

MC: No. You were supposed to be a quote-unquote good sport. You know? Don’t take it too seriously.

NJS: Right. It just started to well up in me. When I went through menopause—it’s kind of like going through puberty. You get a little emotional and hormonal. I just friggin’ lost it on some people who deserved it. Like, I was walking with my daughter when she was 15. This girl is with her mother! We had come from an Italian restaurant, and we were carrying pasta. The guy was catcalling my daughter from a car that was stopped at a stoplight. I didn’t even think. I took my pasta—it was still hot—and I took that lid off, and I just dumped it on him in the car. It was summer, and his window was open. I said, “You better fucking think again before you say that to my kid.”

MC: You struck a pasta blow for all women.

NJS: I think that if I hadn’t been at that point, as a mom going through menopause and just having that anger come up in me, I wouldn’t have done that. But you have this accumulation of all the times you were catcalled as a kid, all the times [harassment] happened to you. This was all happening to me, this feeling like I’m going to explode, as I’m going on Tinder and encountering these horrible guys.

Just because everybody is doing it, and just because people joke about it like it’s a fun thing, and just because the Vows section of The New York Times talks about an “OkCupid marriage,” that doesn’t mean that your experience, which we know from studies is typical, where you got harassing messages, or you got called a name, or you got made to feel uncomfortable, or you went on a date and something horrible happened—that doesn’t mean that your experience isn’t valid. You deserve respect on these apps.

MC: So where do twentysomethings (and others) who want relationships go from here?

NJS: I happen to be older, but this isn’t my truth. This is the truth. This is the truth: that dating apps are bad for women. I’m not saying that for every single woman, because of course there are people who met their happily-ever-after [on an app]. But in general, overall, I think the apps have been very bad for women, and I think they are [part of] rape culture.

I would hypothetically suggest some sort of [bold] move for self-preservation: Everybody put down your dating apps! But unfortunately, I do not think this is likely or possible because (a) the corporations have overwhelmed all of dating; there’s no other way to date right now. And (b) their whole design is to get you addicted. I interviewed [Tinder CSO] Jonathan Badeen for my film Swiped, and he openly and proudly talks about how “Oh, yeah. We designed it to get people addicted.”

It seemed to me that the creators of this app, Tinder, and other dating apps that employ the swipe aren’t really interested in helping us find lasting connections and relationships, as their advertising promises; they really just want us have a relationship with the app itself.

But then, when I was writing my memoir, I started to think further about the swipe as a mechanism that promotes social conditioning. I started to read the work of people like Jaron Lanier, who have railed against how the primary goal of social media is to turn us all into “obedient dogs” (his words) who do just what the platforms want us to do. And I started to think about how this affects women even more cruelly, because as women living in systemic misogyny, we are already conditioned to think and act and feel in ways that support the system that keeps us down. And here are these apps—these addictive apps—that are further conditioning us to think and act and feel in certain ways on top of and in addition to how we are already programmed by society at large.

For example, these apps promote sexualization and objectification; they are all about the male gaze. They promote the idea that women are to be judged on our appearance in just a split second, and rated accordingly, yes or no, fuckable or not. The ramifications of this alone are very real. Some research has shown that women who use dating apps are more likely to feel low self-esteem, to compare themselves unfavorably to other women, and all the rest. So, we become addicted to using this app that makes us feel bad about how we look.

There needs to be, like, a reimagining of this whole thing, but I don’t see it happening any time soon, unfortunately.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This article has been updated.

Maria Ricapito is a writer who lives in the Hudson Valley.