Jessamyn Stanley on Self-Acceptance and the Realities of American Yoga

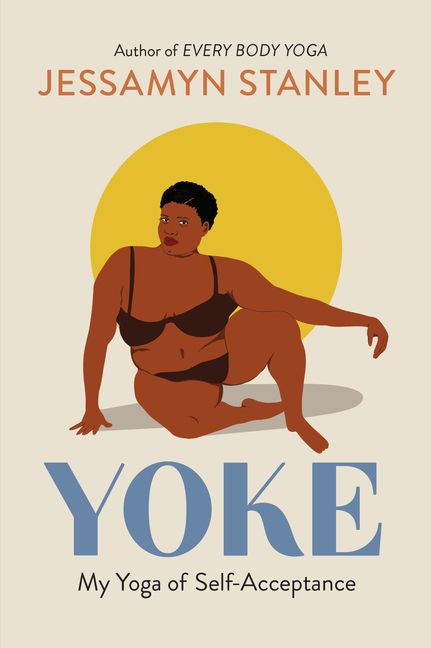

In her new book, 'Yoke,' the yoga teacher and entrepreneur explores American yoga's link to capitalism, white supremacy, and more.

"When the day comes that you no longer need to accept yourself, you're dying," Jessamyn Stanley declares. Stanley is very much alive and still seeking complete self-acceptance for all of the things about herself that are, quite frankly, easier to ignore—her internalized racism, the times she has slut-shamed, the cultural appropriation she has participated in, her capitalist desires. But instead of pretending these aspects of herself don't exist, she decided to write a book for anyone who has ever disliked any part of themselves (a book she has always wanted to read): Yoke: My Yoga of Self-Acceptance (out today).

In her first book, Every Body Yoga (2017), the yoga teacher, author, entrepreneur, and co-founder of We Go High taught readers the basics of yoga—the styles, the poses, the mats—but she knew while writing it this was only a tiny piece of the puzzle. In Yoke (the word yoga means "to yoke" in Sanskrit), Stanley takes the strength, flexibility, and awareness she's learned throughout her years of practice and answers the difficult questions that arise while living the "yoga of the everyday." In other words, applying the lessons we learn on the mat to our daily lives.

Though she discusses systemic issues like racism, capitalism, and white supremacy throughout the book, Stanley isn't in the business of giving history lessons. Rather, Yoke focuses on her own personal experiences and connects them to these larger topics, covering everything from the link between white supremacy and American yoga practices ("If it came from here, it's embedded in white supremacy. Period," she says) to what it really means when we bow our heads and whisper "namaste" at the end of our yoga classes.

Ahead, Stanley chats with Marie Claire about whether or not the American yoga community has learned anything over the past year, how she's reckoned with her own involvement in American yoga practices as a queer Black woman, and her advice for new yogis.

Marie Claire: In the book, you talk about the difference between appropriation and appreciation in yoga. While reading, I kept coming back to the suffering that has been going on in India with COVID-19 and how so many people within the American yoga community haven't spoken publicly about it. Do you have any thoughts on this?

Jessamyn Stanley: Oh my god. It's just the inequity turning over itself. There's no limit to the harm that is, can be, has been, and will be caused by colonization. The COVID response in India is a really great example of that. There's so much fundamental inequity and genocide all connected and rooted in white supremacy. In the yoga community, shit's so basic and people are talking about leggings and handstands and coconut water. No one wants to acknowledge the ways in which cultural appropriation really is such a huge piece of minimizing the impact of this problem. It makes it easier for people to brush [it] under the rug, and it also makes all of us complicit in the system.

But I think that the reason people don't talk about it is because it is hard and it means accepting shame and feeling guilty. Ultimately, you can feel ashamed and you can feel guilty, especially if you are a practitioner of American yoga and you actively benefit from the system of colonization. There's a tendency to just be like, Well, I don't know how to fix that, so I just won't acknowledge it or I won't look at that. It just generally creates apathy and, for me, it's really [about] accepting the role that I play in it and trying to just accept and sit with that.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MC: You ask an important question in the book: "What does it mean for the grandchild of African slaves to find solace from an American yoga practice that's firmly rooted in the soil of white supremacy?" Do you have any clarity on this since you've written these lines?

JS: It's a paradox. I've been thinking a lot about fractals, like how a fractal just continues to recreate itself over and over again. Everything is a fractal. [My ancestors] were murdered for their own spiritual practices to the point where assimilation became the key to survival. It's interesting to me that the white man's reinterpretation of yoga that I was introduced to and that I practice and that has become the lens through which I'm able to see myself, continues to reveal the shortcomings of white supremacy. I don't know if that makes sense, but to really answer your initial question, no, I don't have more clarity on that. I would say that it's all happening for a reason and any way that you're able to find a road back to yourself is good.

If it came from here, it's embedded in white supremacy. Period.

MC: I know a lot of people are probably thinking, How is white supremacy linked to American yoga?

JS: It's sort of my favorite thing because I am like, "Oh my god, yes, let's talk about it. White supremacy is in everything." It's the soil in which we grow literally everything. We can be more specific, I guess, and just say, "Okay, American yoga." I'm then separating classical yoga and American yoga, so that I'm only really talking about lineages of yoga that originated in America in the 19th and 20th centuries. There's no word for how blood soaked this land is. If it came from here, it's embedded in white supremacy. Period.

A desire to not see and understand that makes sense to me. It really does. It certainly wasn't taught in schools. But the reality is that if you look at the genocide of Indigenous people, if you look at the African Diaspora and the enslavement of African people, the indentured servitude of European people, there's so much shit that has happened here and so anything that grows from that is white supremacy.

MC: Do you think the reflecting many people have done over the past year will have any influence on the American yoga community? Or do you think there's still just so much farther to go?

JS: There is still so much farther to go. I will say, I've heard more people talk about racism now than I've ever heard in my entire life and that makes me feel really optimistic because for a long time, before 2020, there was so much make-believe and pretending going on. So much, "Oh, that's not real." But after Blackout Summer, now people are like, "Okay, I can't pretend that this doesn't exist." That is incredible. But I still think that there is a narrative that if you donate a certain amount of money or read a certain number of books or follow a certain number of people on Instagram, then you will fight white supremacy or be the definition of anti-racism or solve racism or something like that. And that will not lead to longterm change. The real work that has to be done is inside of yourself...losing a desire for accolades, losing that desire to have fixed it or get it right, and just really getting comfortable with doing it wrong.

MC: In the book, you write about accepting being disliked and misunderstood. Ironically, being disliked or misunderstood is reflected in some of the press surrounding the book. How are you dealing with the responses you're getting about the link you make between white supremacy and American yoga?

JS: It's funny. I'm obviously here for it. I'm just so glad that people are talking about this. Growing up in the South, I never had any kind of confusion about racism or about people. I really appreciate that in the South people are way more straight up about it than they are in other parts of the country. You can go to Los Angeles or the Bay [Area] or New York and people will literally act like, "I'm not racist. What are you talking about?" And I'm like, "No, you are. It's okay. Everybody is." Now I'm like, "Yeah, let's talk about it." That's why I wrote the book, to provoke that kind of conversation. I'm here for it until it gets dangerous. Then I'm not.

As long as you're breathing, you're living your practice.

MC: Where are you at currently—physically, mentally, and emotionally—in your yoga journey and in building your business? Will there be a day where we don't see Jessamyn on Instagram anymore?

JS: I definitely had a plan a few years ago when I was like, I don't really need to be on social media anymore. I don't feel like it's serving my practice, serving my spirit. And I feel like yoga really asks the opposite of what social media does. Social media is like: Look outside yourself for validation; look to likes and followership. But I realized that there is an opportunity through really living my yoga practice and not just being like, "Oh, look at these yoga poses. Look at what my body can do." Getting beyond that and really being like, "This is how I'm complicated. This is how I'm problematic. These are the things that really come up for me." That feels like a worthwhile expression of myself to share with the world, so that if there's anyone else who feels that way or who sees themself in that way, they can say, "Yeah, I'm problematic too. I have complicated emotions about things too. Maybe I can be myself too." That feels like a worthwhile reason to be on social media, and so that's why I stayed.

To the question of where I am physically and mentally, there's so much going on in my life right now, so much upheaval. Huge things are changing. I have lived with one of my partners for almost a decade and we moved to Durham at the same time, we have gone through many different phases of life here. We are not going to be living together for the foreseeable future and I am going to be moving into a camper trailer with my other partner and I'm going to be traveling around the United States, just living on the road. This is something that I've wanted to do, but it's something that has felt so far off. And also, [I just think,] how am I going to do this?

Yes, I have digital businesses and I share my life on social media, but there are real entities for me to be doing on a day-to-day basis, so I go into an office and I do that kind of work. But we're going to be transitioning to me being 100 percent on the road, 100 percent living on the earth and of the earth in a way that I definitely have not been. I felt very bloated by stuff and possessions and just owning things and what it means to be a part of this machine. I don't know if I can really release that completely because, honestly, I love air conditioning and clothes and all that stuff, but I do want to connect with something real. So, mentally and physically, I'm in this place of, I'm ready to move into the next phase of life, which feels really good.

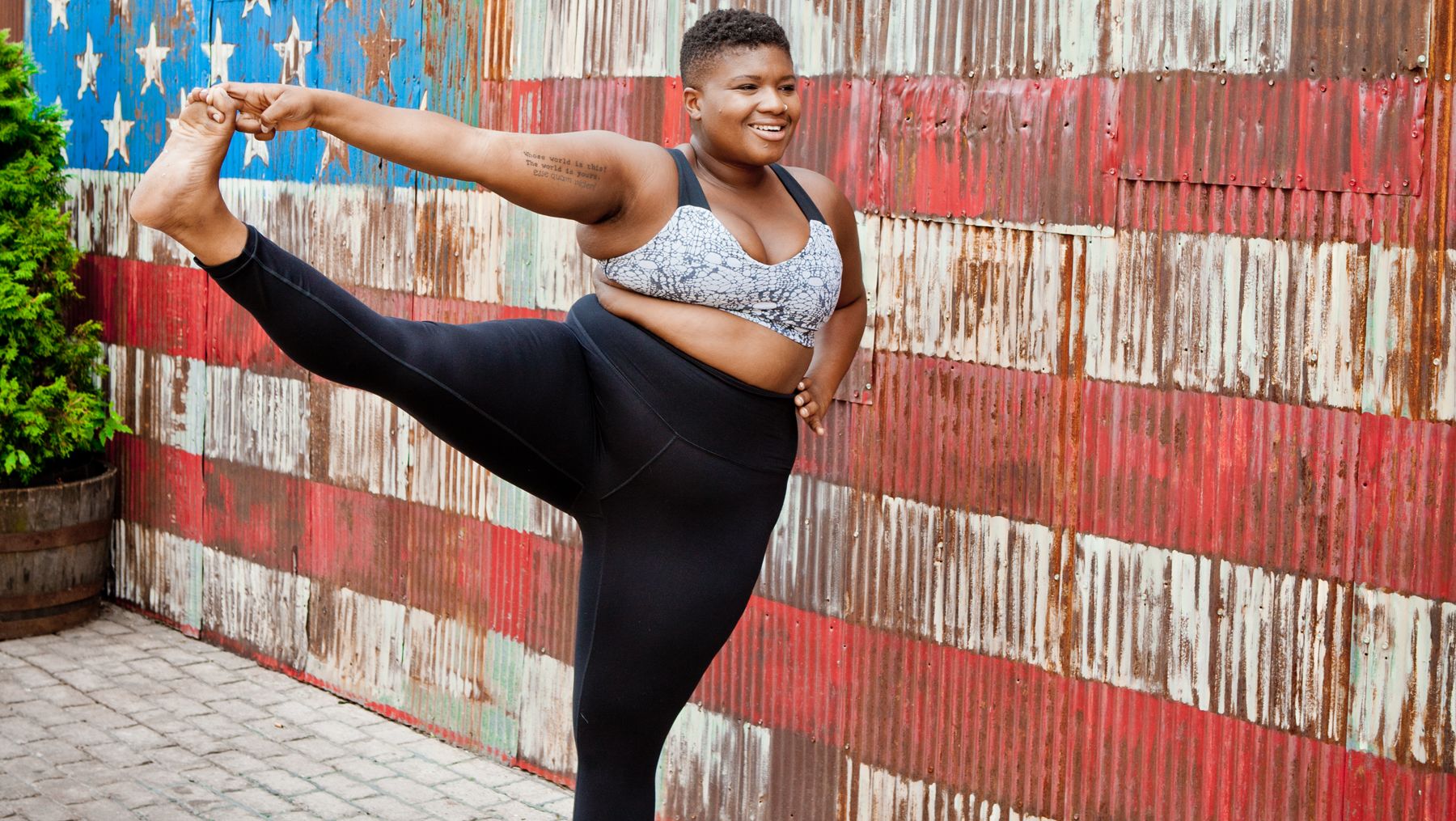

MC: For someone who's thinking about getting into yoga, either as a teacher or a student, what's something you want them to know?

JS: Don't worry about what it looks like. It doesn't matter what your body looks like, it doesn't matter what your practice looks like. Your practice will look like a lot of different things throughout your life because you will look a lot of different ways throughout your life. You will grow and change and get injured and get older and have children (or not) and have accidents (or not). All kinds of things will happen to you and your body will change and your physical practice will also change. And, ultimately, as long as you're breathing, you're living your practice. The best way to share your practice with anyone is to just live your own and not worry about changing anybody else.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

RELATED STORIES

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.