The Last of the Ya-Yas

On the 20th anniversary of the cult classic movie, one writer reflects on her real-life "Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood\201d and her mission to preserve them.

Like Siddalee Walker in Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, I come from a long line of ya-yas—the elusive and nearly-extinct breed of native, Cajun-French speakers.

When Sandra Bullock played Siddalee Walker 20 years ago, I was 15, going into ninth grade in Lafayette, Louisiana. It was the first time I’d seen any semblance of my people on screen. Not the city-dwellers of New Orleans or the Southern Belles from Steel Magnolias, but the spicy Bloody Marys hailing from the “bottom of the boot.” Those are the women who molded me.

There’s a distinct difference between Cajun Country and the rest of the Deep South. They say yeehaw, and we say aiyee. They wear cowboy boots, and we wear waders. They whip up a mean white gravy, and we spend all day perfecting a dark roux. Their grandmas serve sweet tea and our maw maws make coffee milk.

That summer in 2002, Siddalee Walker became my folk hero, and I followed in her fictional footsteps to become a writer in New York City.

"Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood" came out 20 years ago today.

Since relocating in 2011, Divine Secrets has been my go-to movie reference when New Yorkers ask if I’m Greek, Jewish, or Italian. It’s flattering. It means I’ve done a good job blending in— code-switching to sound like an all-American girl who grew up with ham at Christmas instead of seafood gumbo.

But recently that feeling of pride has been replaced with guilt for leaving while climate change threatens our land and language. Our beloved boot-shaped state looks more like a stiletto. Hurricanes displace us, and I worry the next generation of Cajuns won’t grow up with the same sights and sounds I cherish.

So, the time has come on the twentieth anniversary of my favorite Cajun movie, to write our stories down, while my memory is fresh and my 84-year-old ya-ya can keep me honest.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

That’s what Siddalee Walker would do.

Maw maws are the storytellers of the family, the raconteurs. And mine, Lois Marguerite LeBlanc, is no exception.

She passed on that love of stories by taking me to the library before I could even read. We never waited in line. My great-aunt Peggy was the librarian in our small town of Erath, Louisiana.

I remember peeking out from behind my picture book and watching a whole movie play out on my maw maw’s face as she read a novel. I wondered how powerful words must be to entertain the most entertaining person I knew, how moving a story must be to make my maw maw, a triple-crown Cajun Festival Queen, sit still.

My maw maw Lois (holding her knee on the hood of the car) with her gang of ya-yas as teenagers in Erath, Louisiana, in 1954.

I wanted to write words like that some day.

With my favorite movie on my mind, I called my maw maw Lois. It’s one of her favorites, too. For weeks and weeks she has been patient with me, telling and retelling me some of my favorite stories about our family.

The opening fire-ceremony in Divine Secrets could have easily been filmed on our family farm. She reminded me about the lore of our land, the secrets in the pecan trees. Legend has it that parts of pirate Jean LaFitte’s treasure are buried on our property. And come nightfall, if you aren’t home before supper, the rougarou, a werewolf living in the marsh just behind the camp, will get you.

I ask about what my canaille cousins (mischievous cousins) and I were like when we were little. She tells me about the time my mom, her eldest child Mary Helen, painted her bedroom a pepto-pink.

Me with my maw maw Lois in 2010 in Lafayette, Louisiana.

A couple of weeks later, I get an envelope in the mail with a stack of photos and records of a young girl. But then my maw maw tells me about a woman I’d never met named Rita Leleux. She was my great-grandmother with the same valiant spirit as ya-ya leader Vivi Abbott Walker in Divine Secrets. She is tall with two, long brown braids. She stands proud despite being in the background of her brother.

And there’s a newspaper clipping. Rita Leleux, with the highest grades in her class, was selected to become one of the first one-room school teachers in the Louisiana swamps in 1917. She was only 18 years old.

According to the news story, Rita Leleux woke up and set off on a pirogue, a wooden boat, through the bayou to her schoolchildren Monday through Friday, rain, sleet, or snakes. Some of the children were barefoot, already up for hours doing chores but who would still make sure to get to the schoolhouse early, in the darkness of a damp winter, to haul the coal and light the heater.

Some students spoke only French and some spoke only English. Neither group could read or write. Most were descendents of the Acadiens (“the Cajuns”) and the surrounding tribes, like the Mi'kmaq, whose families survived the Expulsion (Le Grand Dérangement) in Nova Scotia Canada in the mid 1700s, Entire families were torn apart and put on different boats, some to France, the islands and the newer port city of New Orleans, never to be reunited.

My great-grand mother Rita is second from left. This was taken circa 1912, a few years before she became a teacher.

Rita taught them how to write their names so that they didn’t have to mark an “x” as a signature. She taught them their prayers in French so that they could get their first communion. She taught them English so that they wouldn’t get beaten when they went on to more formal American schooling.

Before she married at 24 and had 5 children of her own, the Vermillion Parish boys and girls were her babies.

I tell my maw maw Lois I wish I could have known her. Rita died the year I was born, just nine months before I entered the world in 1986. It was illuminating to see Rita so wide-eyed and girlish. I’d only ever seen her in photographs with gray hair. She had my maw maw Lois at 41 years old in 1938.

I ask to see my maw maw Lois’s baby pictures next. She mails me what she could find, along with a surprise: a photo of my maw maw posing with her gang of ya-yas as teenagers. It’s reminiscent of the iconic car scene in Divine Secrets where the girls speed top-down (and practically topless) to escape the scorching Louisiana heat before being stopped by the police.

It’s a photo that makes my heart flutter.

There they are all together, smiling under a cypress tree frozen in time. Her fondest memories were in this car. This was long before AC. Dolores, her best friend, would drive them nowhere and everywhere.

It was the only time they remember him being stern: 'Laissez ça tranquille mes enfants. Leave that alone, my babies.'

In the summers they’d load it up for picnics at Cypremort point. They’d swim and float and end the evening with a slumber party at Lois’s, staying up all night giggling in front of box fans, splayed out on the cool linoleum floor gossiping till dawn.

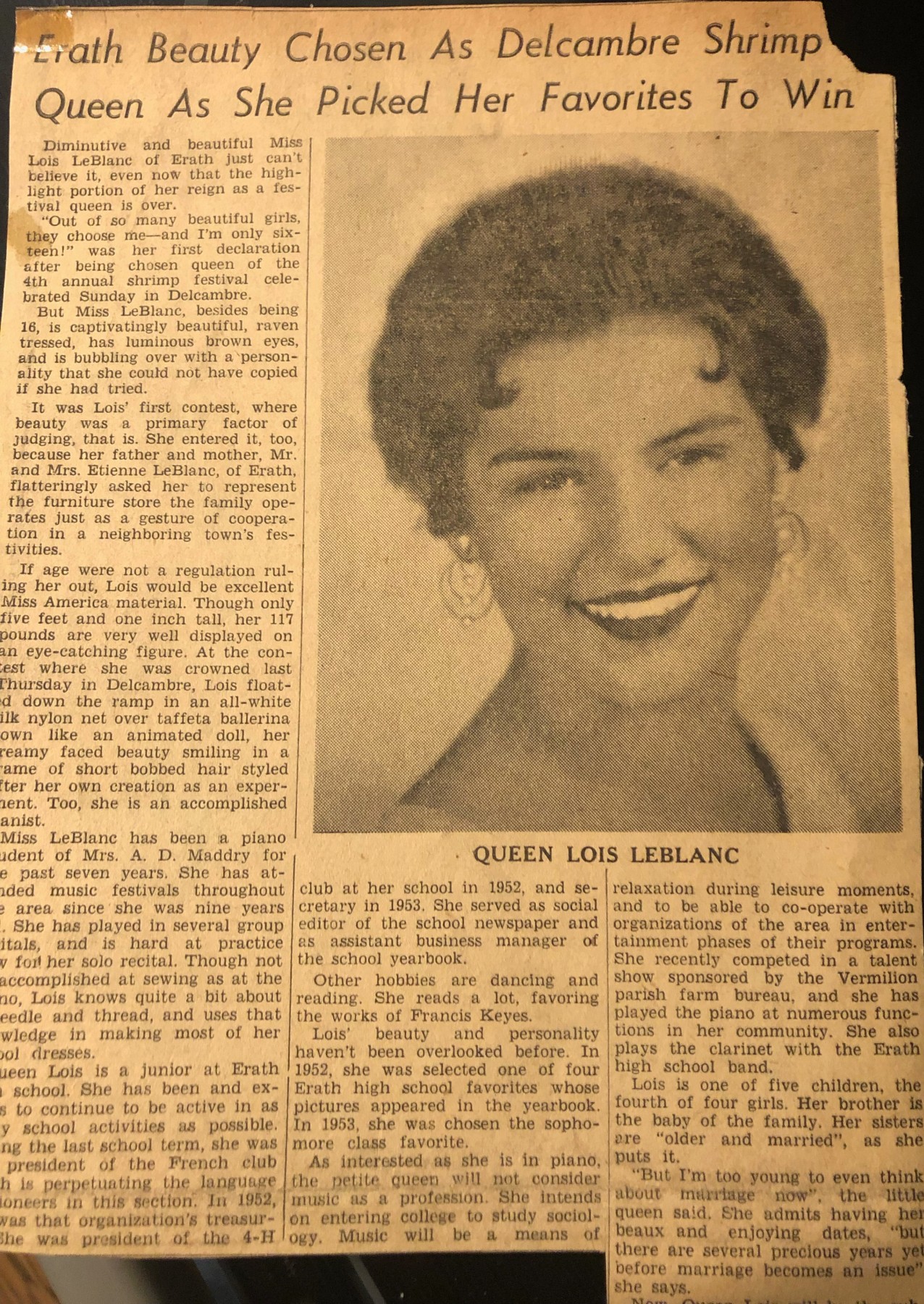

It was one of these sweltering summers that Lois got her first big break. A representative from the Delcambre Shrimp Festival came to her father's furniture store and asked if he’d sponsor a girl in the upcoming beauty contest. When asked if he knew one, Etienne, Lois’s father, said he did. The prettiest girl he knew was his daughter.

“She’s 15 right now but her birthday is in August so she’ll be old enough for the contest,” he explained.

My maw maw said she was hiding in the back eavesdropping, muffling her squeals when they let her enter. She tells me about how being crowned the Shrimp Queen was one of the best nights of her life.

Maw maw Lois in the local papers after a pageant win.

From there, maw maw Lois went on to attend the Mardi Gras Ball in D.C. in 1956 teaching Capitol Hill interns how to two-step and avoiding microphones by all means necessary.

The portraits of her are stunning. She looks so much like her dad, who always thought she looked like his mother, Olivia. They shared the same, deep dark eyes and hair, tan skin and high cheekbones.

Once, maw maw Lois and her sisters found a picture of Olivia in the attic in an outfit they’d never seen before. It was ornate. When the girls asked their father about the clothing, it was the only time they remember him being stern: “Laissez ça tranquille mes enfants. Leave that alone, my babies.”

They never asked again.

There were rumors my great-great-grandmother Olivia came from a tribe in Texas but no idea why it would be so secretive.

My maw maw Lois and I are determined to learn more, and I am determined to write Olivia’s story next.

This isn’t the last of the ya-yas.

Megan Broussard is a writer and producer in New York City with work in The New Yorker, Marie Claire, Slate, McSweeney’s, The Rumpus, Reductress and more. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @megsbroussard.