Jo Piazza and Christine Pride Tackle the Complicated Topic of Motherhood in 'You Were Always Mine'

Following the Covid childcare crisis and fall of Roe, the book's theme is more relevant than ever.

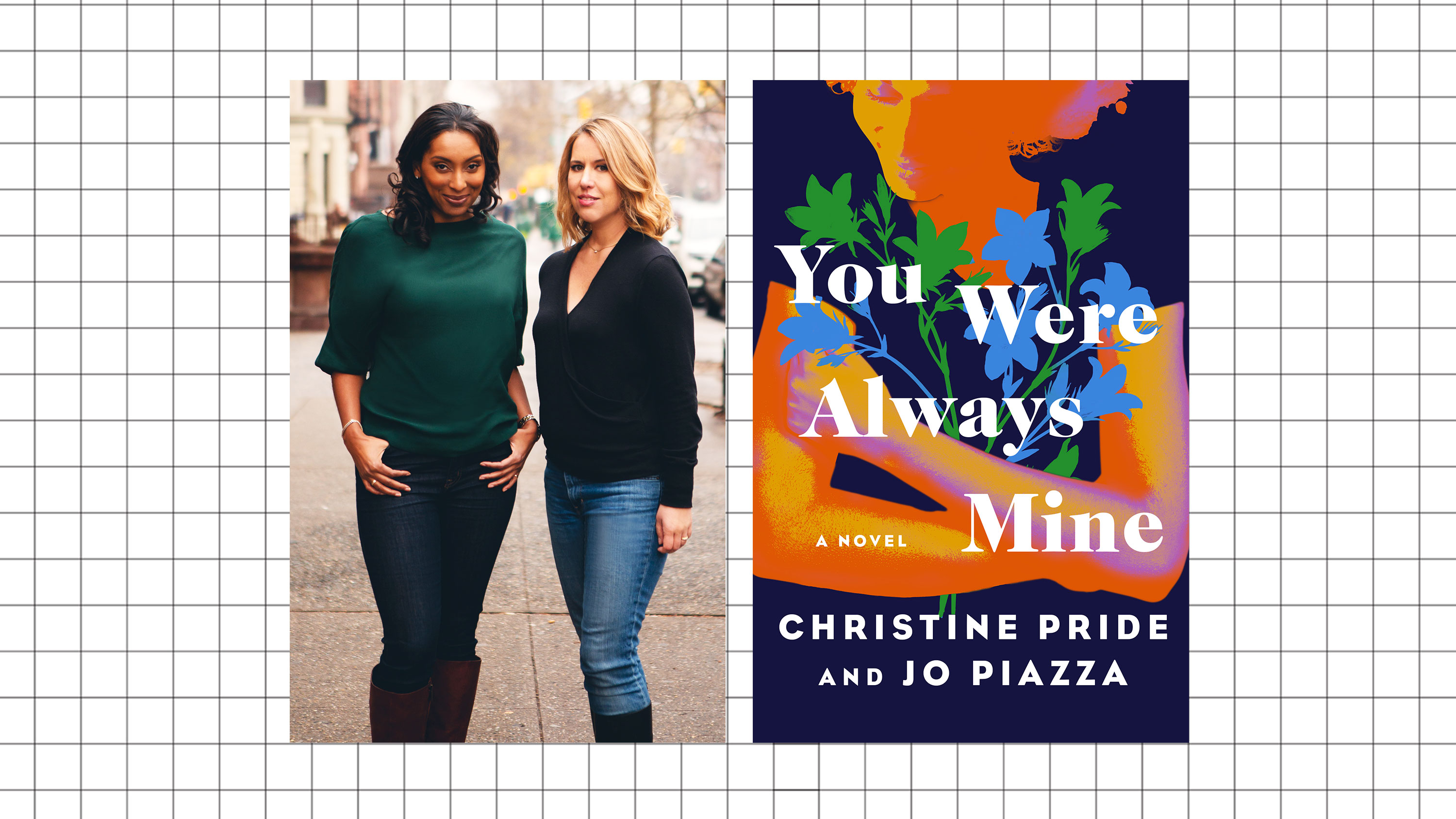

Following the success of their last book together, We Are Not Like Them, Jo Piazza and Christine Pride are back with another thought-provoking, conversation-starting, extremely relevant novel: You Were Always Mine. The book, featuring an evocative cover illustration by artist Laywan Kwan revealed here for the first time, again examines race, but this time also asks readers to grapple with their notions of motherhood—who gets to choose (or not) to be a mother and what it means to be a quote-unquote good one.

You Were Always Mine tells the stories of Daisy—a young woman who feels that the best thing she can do for her infant child is to abandon her—and Cinnamon, the woman who finds Daisy's baby. Daisy wants Cinnamon to find her daughter because she trusts her, yet Cinnamon's own upbringing—including time spent in the foster system—has complicated her feelings about being a mom.

Here, the authors—who have chosen very different motherhood paths themselves—give a bit of a sneak peek at the book (it hits shelves in late spring), discussing what they hope audiences will think about as they read You Were Always Mine and how the book has changed since Roe v. Wade was overturned this summer.

Marie Claire: Your previous book together was very much about race relations, in particular friendship between Black women and white women. This book is also about race, with the premise being that a Black woman finds an abandoned white baby. What was the reaction to the theme of the last book and how did you evolve your examination of that theme for this book?

Jo Piazza: We prepared for every possible reaction to We Are Not Like Them knowing that we were talking about race in America during a very fraught time. And what we've gotten back, just the outpouring of support, was completely... I mean, it was beyond what we expected. What we learned is that people were so intensely hungry for ways to start this conversation, that they've been dying to do this, and it's hard to talk about race. Our book gave them entry points because, through the characters, and through the story lines, they were able to say things they never would have said, because they were terrified of asking those questions, of starting those conversations. We done so many book events, and everyone was just so incredibly excited for a way to start that conversation, which is exactly what we want to be doing with this next book.

Christine Pride: One thing that we're really excited about and proud of in terms of the reception for We Are Not Like Them is that we had such a diverse audience of readers. ... That was really gratifying because it allowed people to have connections across races and have conversations across races that we don't normally have. Sometimes, even if you're talking about race, you're talking about race among people who look exactly like you and share the same experiences, which is important, but we really see a lot of value in people having talked about this book and then talked about race with people that were different from them.

MC: And so taking that experience, how did you imbue learnings from that or move that conversation forward for this new book, in which race is a major theme but a secondary one?

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

CP: I think it's it's the same idea that race really affects everything, right? And that's what our books really delve into and that's what we're very interested in as writers. You can write a story that feels universal about friendship or about motherhood. But when you add race to the mix, it affects all of the tentacles, all the dynamics, all the relationships. And that's what we're really trying to show in this story. And, if anything, we wanted to double down in the wake of We Are Not Like Them on really pushing that, since people seem to really respond to this idea of, Why do I think a certain way about race? Why do I react to certain way when this character says something or this character does something? And pushing readers to think about...how they view the world. And then how they can view the world differently, through both our characters' eyes and really putting the reader in these characters' shoes.

MC: In addition to race, motherhood is the main theme of this book. Jo, you're about to have your third child; Christine, you're child-free by choice. How did those aspects of your personal lives factor into the writing of this novel?

JP: My gosh, I mean, in everything that we did. As Christine said, we're really passionate about tackling race in intimate spaces. And so for this book, we wanted it to be in motherhood, in the parenting space. We came up with this idea for the second book to do together back in 2018. So, well before the world was put in a state of upheaval when it came to motherhood. But now it feels so much more important and poignant and fraught to be discussing. What does motherhood mean in America? Really, how do you choose to become a mother or not? And who gets to make that choice?

Christine and I have had different paths In life. Christine is a godmother and an aunt to so many children and has chosen to be child-free. I have not stopped breeding in six years now. ... We haven't seen anything really great recently in the commercial fiction space about: How do you make that choice for motherhood? Who gets to make that choice for you? Is it a privilege, or is motherhood a right? And we want to explore that through the characters of Cinnamon and Daisy.

CP: Because Jo and I come at it from completely different perspectives or life experiences, it is almost like We Are Not Like Them in that 'she said/she said' perspective. We wanted all the different ranges of choices and thought processes and decisions to be represented. There's no one right way to become a mother and there's no one right way not to be a mother, right? There's so much judgment in our society about those decisions, so many preconceptions about that, especially as a woman that's child-free by choice. A lot of people have a lot of thoughts and judgments about that, some spoken, some unspoken, some one-on-one, some societal of: You're gonna regret this or, you know, is it really you're child-free by choice? Like, you just couldn't become a mother. We wanted to show that through the lens of really relatable characters; people wrestling with those particular issues.

MC: This idea of when, if, and how to become a mother—certainly there are many on the extreme right and the anti-choice movement who make motherhood out to be the pinnacle of female achievement. And there are many deeply committed, enthusiastic mothers who are staunchly pro-choice. And then there are questions many women struggle with: Do I want to be a mom? Can I become a mom? It's obviously a complex conversation. Do you have something you're particularly hoping to add to this conversation with this book? What do you hope this this book allows readers to do?

CP: We did not have a moral agenda. We were not trying to stay what is right, what people should do, what people shouldn't do. I mean, we fundamentally believe in reproductive choice and in women's rights, but otherwise we really wanted to show by virtue of the characters wrestling with these decisions and the characters thinking about their choices to be a mother or not—and when and with whom and what are the races of these kids.

Those are things that we're hoping that when you see the characters wrestling with them, and you have empathy with their struggles and ruminations and reckonings, that that allows you to think about your own choices. And other people's choices, too. But think about them from the viewpoint of empathy and understanding rather than thinking about them from a position of judgment or even thinking about them from a legal position, right? Sometimes we get caught up in the laws and the rules and the Supreme Court decisions. And not the case-by-case... you know, a woman's life being affected fundamentally and permanently one way or another.

JP: We want to get across just how much more complicated this decision is than I think typically gets presented, right? Because it does become such a binary choice: You become a mother, you don't become a mother. And we wanted to introduce all of the nuance and the shades of gray and get people talking about that. Because I do think that we get so wrapped up in the identity politics of this versus this that, that we don't keep the human being—the woman and child—in the conversation. We want to re-center the conversation on those two people.

We talked about [Christine's work with Haven] so much when we were writing.

CP: I'm a big believer in abortion. I had an abortion when I was 19 that I'm very vocal about because...it did fundamentally... obviously my life would have been very different had I—

JP: I revealed my abortion in Marie Claire.

CP: There we go. Since then I've been a staunch advocate. And so I started volunteering with this organization in New York called Haven. I host women who need to come to New York City to have abortions from other states. It's really a woman-to-woman thing. You host them, you provide dinner, you take them to and from their procedure. A lot of times, women are traveling alone, across many states to do this; sometimes in secret. And so it really is such an honor and a privilege to open your home to them.

But you realize doing this work that no two stories are exactly alike. Just the reasons for needing to have an abortion—health, race, age, marital status, circumstances. ... We want this story to be representative. But at the same time, there's an infinite number of stories and an infinite number of ways people become mothers or don't. And so this is just one glimpse into that, but it was informed by really being able to talk to strangers about their experience.

The other personal aspect I have to this is that my parents are foster parents. They were Black foster parents and fostered two children whom they eventually adopted, and so I've seen it from that angle as well.

But also we never see—and this is, I think, important in terms of what we really wanted to do in terms of turning the trope on its head, because we could have written a book where all the characters are Black or all the characters are white. There's another whole dynamic here of who has the right to raise other children. And we never or we very rarely see Black parents with white children. We want people when they're reading this to really think about that. They're gonna have a reaction to, Oh this Black woman has this white baby. I never thought about the consequences or the complications that would come from that. Because we so often see it the other way. We really wanted to break through that.

MC: You started writing You Were Always Mine before the overturning of Roe v. Wade. So, first of all, how do you write such of-the-moment novels? And, second of all, has your perspective on motherhood changed since the Dobbs ruling and did you rework like any parts of the book in the editing process?

JP: It must be the fact that I'm so Sicilian, right? Like, I think I'm a witch. Christine and I are both like these witches…

CP: You have a crystal ball.

JP: Frankly, we just like find stories that we're both passionate about. We've been so passionate about this idea for so long and it just happened to become a huge part of the zeitgeist.

The book was done before the decision… We were in edits and we could revisit it. There are so many different mothers in the book who would have been impacted by the [Dobbs] decision in a lot of different ways. And we're not just talking about the current generation of mothers on the current timeline; both Cinnamon's mother and Daisy's mother were young women who got pregnant not necessarily by choice. Who had struggled with raising their daughters, but for whom abortion was probably not an easy option for them, and we watch how that generational trauma trickles down to both Cinnamon and to Daisy.

We don't say what state it's set in. We're very careful about that. But we did, after Roe, make it more clear that it would be difficult for Daisy to get an abortion. She would not have really had access to one and that forced her to struggle with some choices that are so impossible for a 19-year-old girl who does not want to be a mother. She has these big dreams. She wants to live in the world in a way that having a baby would really preclude that. We wanted to get that across and it became so much more important after Roe [fell].

But it is not our job to moralize or preach on the page. We want readers to come to their own decisions. We, I think, tried to have as much of a soft touch with saying: Daisy did not have this option and we will watch her struggle and let's talk about her struggle and let's bring up the questions about her struggle. Because we think that just leads to so many more interesting conversations for for book club readers.

CP: And I want to add, too, that class is a real part of this in the same way it was in We Are Not Like Them. I think a lot of times we think of motherhood being this exalted state. And we have this very white affluent notion of motherhood: Like, you sit down and you look at the calendar and you make a choice and you decide you're having a baby in spring and then you order all the beautiful things from the Internet, etc etc.

JP: With your partner who's totally on board.

CP: And the fact of the matter is, you know, 90 percent of women in the world are not in those particular pregnancy circumstances. ... And they don't have any money to either have an abortion or to raise a child. And for all the mothers in this story, notably, that's the case. Nobody is a wealthy woman who has all the resources at her disposal to decide to have a baby or not. And that is a very different set of circumstances that we don't talk about nearly enough.

MC: Daisy abandons her baby. Cinnamon had been abandoned when she was young. Is there also a commentary here on what society defines as a "good mother?"

CP: Absolutely. Which is an impossible bar, right? Everybody's notion of what is a good mother is so different. And it's so based on your worldview and your perceptions of things. It's why so many Black mothers end up in the [Child Protective Services] system, because they're judged by a different set of standards of what "exalted motherhood" is. And so we have to be really careful in our society about putting the framework of "this is what good parenting looks like" or "this is what a good mother is." Who is worthy of raising a child is really relevant in terms of a child-welfare standpoint when so many kids get taken away because of these standards and end up in foster care like Cinnamon did.

JP: I think we see this from both Daisy and Cinnamon's perspective. Daisy, when she abandons her baby, calls herself a monster, [but] she still believes that she is doing the best by this child by not being her mother, by giving her to someone who she thinks can raise her properly. She says, "I can't do this." That is her ultimate act of good motherhood for [her baby]. And then we watch Cinnamon grapple her whole life with thinking she won't be a good enough mother because of what happened to her, because she doesn't have these role models, because she grew up in the foster system. And thinking that she's not worthy of motherhood, which is also something that we never see on the page, because we do see such a privileged slice of mostly white, very upper-middle-class motherhood.

Correction: An earlier version of this story mistakenly stated that the character Cinnamon is the character Daisy's career counselor. We regret the error.

Danielle McNally is a National Magazine Award–winning journalist. She is the executive editor of Marie Claire, overseeing features across every topic of importance to the MC reader: beauty, fashion, politics, culture, career, women's health, and more. She has previously written for Cosmopolitan, DETAILS, SHAPE, and Food Network Magazine.