Could This Be the Cure?

For decades, a New York writer struggled to understand why she felt so stuck. It wasn't until she tried MDMA —and finally processed a dark episode from her past—that she got her answer.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Marie Claire Daily

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sent weekly on Saturday

Marie Claire Self Checkout

Exclusive access to expert shopping and styling advice from Nikki Ogunnaike, Marie Claire's editor-in-chief.

Once a week

Maire Claire Face Forward

Insider tips and recommendations for skin, hair, makeup, nails and more from Hannah Baxter, Marie Claire's beauty director.

Once a week

Livingetc

Your shortcut to the now and the next in contemporary home decoration, from designing a fashion-forward kitchen to decoding color schemes, and the latest interiors trends.

Delivered Daily

Homes & Gardens

The ultimate interior design resource from the world's leading experts - discover inspiring decorating ideas, color scheming know-how, garden inspiration and shopping expertise.

"It’s one of the most horrifying things I have ever heard," Lily* repeated as I washed down the first of two ivory pills with cucumber-mint water. “And I’ve heard it all.”

Staring out the bay windows of her pre-war apartment, waiting for the drugs to kick in, Lily and I chatted casually — about our dogs (her sweet Cavapoo was nestled in my lap), mutual friends, and what happened to me all those years ago in that classroom. The very reason I was sitting on Lily’s couch.

About 30 minutes later, my body started to tingle. “I think I feel something,” I told her. Gliding across the wood-paneled room in a white flowy dress, with the calm of someone who’s done this many times before, Lily dimmed the lights and flipped on the soothing classical music that would become my soundtrack for the next seven hours. As I slipped on the eye mask and stretched out on the couch, I took deep breaths, ready for wherever this ride would take me. But just like those nerve-racking moments before the roller coaster drops, my inner voice screamed, Oh, no. This is scary! What have I done?

Thankfully, the dread was fleeting, and soon, there’d be nothing to be afraid of anymore. But first, I’d have to go back to that classroom.

I turned 40 this year, so the details are foggy, but here’s what I remember: I was standing at a white board with a handful of other 9-year-olds. My assignment was to spell out a list of words, including “does,” and I mistakenly inverted the O and the E. It was an error that my teacher, Mr. C.—a sturdy, white-haired bear of a man in his early 50s, who favored short-sleeved oxfords and wire-rimmed eyeglasses—caught right away.

What few boundaries I had as a child turned to ash, and in their place sparked an instinct to light myself on fire so others could keep warm.

Gleefully, he stopped the lesson. He hoisted me up onto a table, settled inches below me on a small plastic chair, and rested my leg on his thigh. Then, as the entire class watched, Mr. C. slowly unbuckled my little shoes, stripped off my white socks, lifted my foot up to his mouth, and sucked on my toes for what felt like a lifetime. “D-o-e-s, t-o-e-s. Get it?” he said. As my tiny hands gripped the edge of the table, he told me he was teaching me a lesson I’d never forget. That one I’ll give him.

Even now, I can still feel my foot inside his slimy mouth; I can still see the stunned looks on my friend’s faces. In that instant, what few boundaries I had as a child turned to ash, and in their place sparked an instinct to light myself on fire so others could keep warm. And so, I pretended to laugh at his stupid jokes, downplaying the ghastly show in which I’d suddenly been cast as an unwilling star, shoved to center stage. I went along with the act.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

But inside, a rush of emotions washed over me: confusion first (the only time a grown man had touched my toes was my father, during “This Little Piggy”), humiliation next, then fear and shame. Sadness and white-hot rage didn’t rear their heads until much later. Looking back, it was like a deranged striptease. Even then, I knew it was wrong. But what came after was possibly even more devastating.

I hit the jackpot when it comes to mothers. If I had a dollar for every time someone gushed, “I love your mom!” the moment they realized I’m her daughter, I’d have a closet full of Valentino. But we never talked seriously about what happened that day, and the hammer never came down on Mr. C. I have a vague memory of a female teacher or another mom—somebody—mentioning the incident to my mother while I sat in the back seat of her station wagon when she picked me up from school that afternoon. The only thing I remember is that whoever it was shrugged the whole thing off as a joke. So that’s what it became. My mother rolled up the window, and we drove away.

No one could face the harsh reality that a pedophile, hiding in plain sight as a well-liked elementary school teacher, assaulted me in broad daylight before a live audience. Even though my mother couldn’t possibly have foreseen the consequences, nor would she ever have intentionally put me in harm’s way, her silence intensified the pain I’d feel for decades to come.

For context, the ’90s were a different time. It was the year of the Menendez trial, where Erik and Lyle tearfully laid out in graphic detail the unspeakable sexual abuse they repeatedly suffered at the hands of their own father.

Most people didn’t believe them. My mother believed what happened to me, she just didn’t understand the gravity of what that sicko Mr. C. did. And he was no dummy. If he’d violated another part of my body, there’s no question my mother (and father) would’ve raised hell. A worrisome detail is that there was another adult in that room—a younger, female teacher—who watched the whole thing and didn’t put a stop to it.

While everyone largely forgot about the incident, reminders followed me everywhere. I became obsessed with excelling academically, athletically, artistically, and socially. To prove that I was a good girl, I sought out validation in every form: as president of student council, a captain of multiple sports teams, a star of school plays, and a straight-A student (except in math; I can’t do math). I wanted to be the smartest, the prettiest, the most popular, the best dressed, and whatever other awards and accolades I could gobble up as if I were Cookie Monster. I didn’t know it then, but I was using these achievements as a shield to protect me from the same pain, shame, and humiliation I’d felt that day in third grade.

When I started high school, I became so guarded that my mother read my diary in a desperate attempt to try and learn something, anything, about what was going on with me. For decades, I hated being touched by anyone. “To hug you,” my mother joked, “is like hugging a diving board.”

Guys scared the hell out of me. Any one of them who expressed interest instantly gave me the ick. In college, I developed a knack for choosing emotionally unavailable men. I had zero boundaries, ignored red flags, catered to their needs while neglecting my own, and settled for far less than I deserved—all patterns I’d learned for the first time when I was 9.

For virtually my entire 20s and 30s, I felt as though something was blocking me from—forgive the phrase—living my best life. I pictured this block as a cork just waiting to be popped open, like a bottle of wine. Except, for the life of me, I couldn’t find the damn bottle. How can you fix something if you don’t even know which pieces are broken? It never crossed my mind that it was, in fact, Mr. C. All the adults around me had dismissed what he had done as a joke, so I did too. That mindset carried all the way from childhood into adulthood, leaving me hopelessly blind to what was getting in my way. Often the best answer that I could come up with was that it was me.

What so many people don’t understand about childhood trauma is how profoundly it submerges, settling inside you so seamlessly that it’s woven into your DNA.

The first time I heard about MDMA therapy was from my mother. “She told me it changed her life,” she shared with me about her close friend.

My Spidey senses pricked. For a long time, my mother knew I’d felt stuck. I had stopped going to talk therapy a year prior. It had started to feel like I was banging my head against a wall. I'd talked my daddy issues to death and could gladly take my $150 and spend it elsewhere. At 39, I was treading water. I’d been pounding on Hollywood’s doors as a writer and producer for years, and only occasionally would someone let me in through a side window. Meanwhile, my last remaining group of single girlfriends had all stumbled into relationships seemingly overnight. I was desperate to start the next chapter. I was ready for MDMA.

Psychedelics have been increasingly popping up in the mainstream over the past handful of years. This resurgence, which includes psilocybin (mushrooms), ayahuasca, and MDMA, is in large part because a number of scientific studies that began in the 2010s have shown promising results around the drugs’ ability to help with many mental health conditions, especially those that are resistant to other forms of treatment.

One of the most notable studies around MDMA and mental health, which was conducted by MAPS (the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies), focused on MDMA’s ability to help people suffering from PTSD when used in conjunction with therapy. The study included multiple female participants who had experienced sexual assault, childhood abuse, and military sexual trauma and who reported that they experienced an 88 percent drop in PTSD symptoms after undergoing psychedelic therapy. The results were so compelling, the FDA granted MDMA “Breakthrough Therapy” status in 2017—a step that acknowledged the drug’s promise in treating PTSD more effectively than traditional methods, like antidepressants. Still, in 2024, the FDA declined approving MDMA-assisted therapy, citing the need for more data. This means that MDMA (and most other forms of psychedelics) remains a Schedule 1 class drug; to possess or consume it, in most states, is a felony—which keeps the psychedelic-therapy movement underground.

My mother’s friend passed on Lily’s contact information and coached me on how to approach her.

Before we scheduled my MDMA session, Lily and I spoke on the phone about what might surface while I was on the drug. Mr. C. was the very last person I mentioned. Lily’s breath caught. There was silence on the other end. It had taken 30 years for someone to validate my trauma by finally calling what Mr. C. did by its true name—childhood sex abuse. This may sound odd, but at that moment, a tidal wave of relief crashed over me. And buried in the sand, I found that bottle.

But even then, I couldn’t admit it to anyone. The day before my session, my father and I spoke about Mr. C. for the first time. He swore he never knew, but he didn’t understand how it could still be affecting me three decades later. “You don’t think this could possibly be what’s blocking you now, though?” he questioned. I hesitated, then cracked, and mumbled that I wasn’t sure, even though, by now, I was. I immediately backpedaled, jumping to assure my father that I didn’t think of Mr. C. often, which was true. But I was still bargaining, burying, and downplaying at my own expense.

I arrived at Lily's apartment nervous. Not about taking the pills or getting into trouble—nervous that they wouldn't work. Lily assured me that no one she’d administered MDMA to had ever regretted it, though everyone reacts differently; some talk, some cry, others scream out. I didn’t make a peep.

The best way I can describe the feeling is dreaming while you’re awake. You’re still in control. It’s not like you believe you’ve turned into a bald eagle or the reincarnated spirit of Cleopatra. My experience on MDMA, what’s often called a “journey,” felt less like a therapy session. It was as if I’d stepped into an entirely different realm, a place that felt surreal, mystical, cinematic.

My first stop: that classroom. Mr. C. came to me as a demon. Like Heath Ledger’s Joker, except less green and red, more grey and black; sagg ing, midnight skin, with charcoal eyes and shimmering obsidian lips turned upward into a ghoulish smile. Suddenly, my 9-year-old foot was inside Mr. C’s snarling mouth, his reptilian tongue darting all over my skin. I watched as his disgusting slobber seeped under my toenails and into my flesh, a part of him becoming part of me. Then scenes from my life over the next 30 years flickered across my mind like a film projector, scenes that had nothing to do with him—until the camera panned and revealed that there he was, lurking in every corner. The part of him that stayed with me, haunting me, following me into every room I entered. He’s always been there. I just didn’t know it. At least my conscious self didn’t.

The miracle of my MDMA journey is that it reframed my trauma into visual and visceral terms that I could finally understand, twisting it into a chilling ghost story where I played not just the hero but the audience too. I watched my 39-year-old self take elementary-school me by the hand, and together, we faced the demon. As we stared him down, Mr. C. grew larger, his face distorting into a fiery, hellish version of the disembodied voice in The Wizard of Oz. We stood side by side, unfazed by this flaming asshole, chanting our battle cry: “I release you, I release you, I release you.”

The rest of my journey unfolded like a walking tour, my subconscious guiding me through my own memories—mostly linked to my relationships with men, my father, and myself—that revealed how a single moment altered my life in ways I’d never even considered. The score of Lily’s classical music bent to whatever the moment conjured; it was eerie at times, heartbreaking at others, ultimately triumphant.

The next day, I walked my dog around New York like Joseph Gordon-Levitt in 500 Days of Summer—dancing in the streets to Hall & Oates after he sleeps with Zooey Deschanel. And I felt lighter, like I’d shed a skin. So many puzzle pieces now fit, dots connected. Tears of joy flowed as I texted my mother—for not only telling me about MDMA but urging me to try it.

What so many people don’t understand about childhood trauma is how profoundly it submerges, settling inside you so seamlessly that it’s woven into your DNA. It can feel worse than an ugly scar because it’s invisible to the world, even to you. Compared to a violent assault (clearly abuse), my toe sucking felt ridiculous, which added yet another layer of shame and confusion. I would think, Don’t be silly, Serena. Surely your block can’t be that. But denial is only one of trauma’s many disguises, on a revolving rack of costume changes. No treatment is one size fits all, but for me, those MDMA pills were magic because they allowed me to really see that.

Three weeks after taking MDMA and three days after I turned 40, I sold my first television series. I popped the cork on a bottle of wine to celebrate.

*Name has been changed

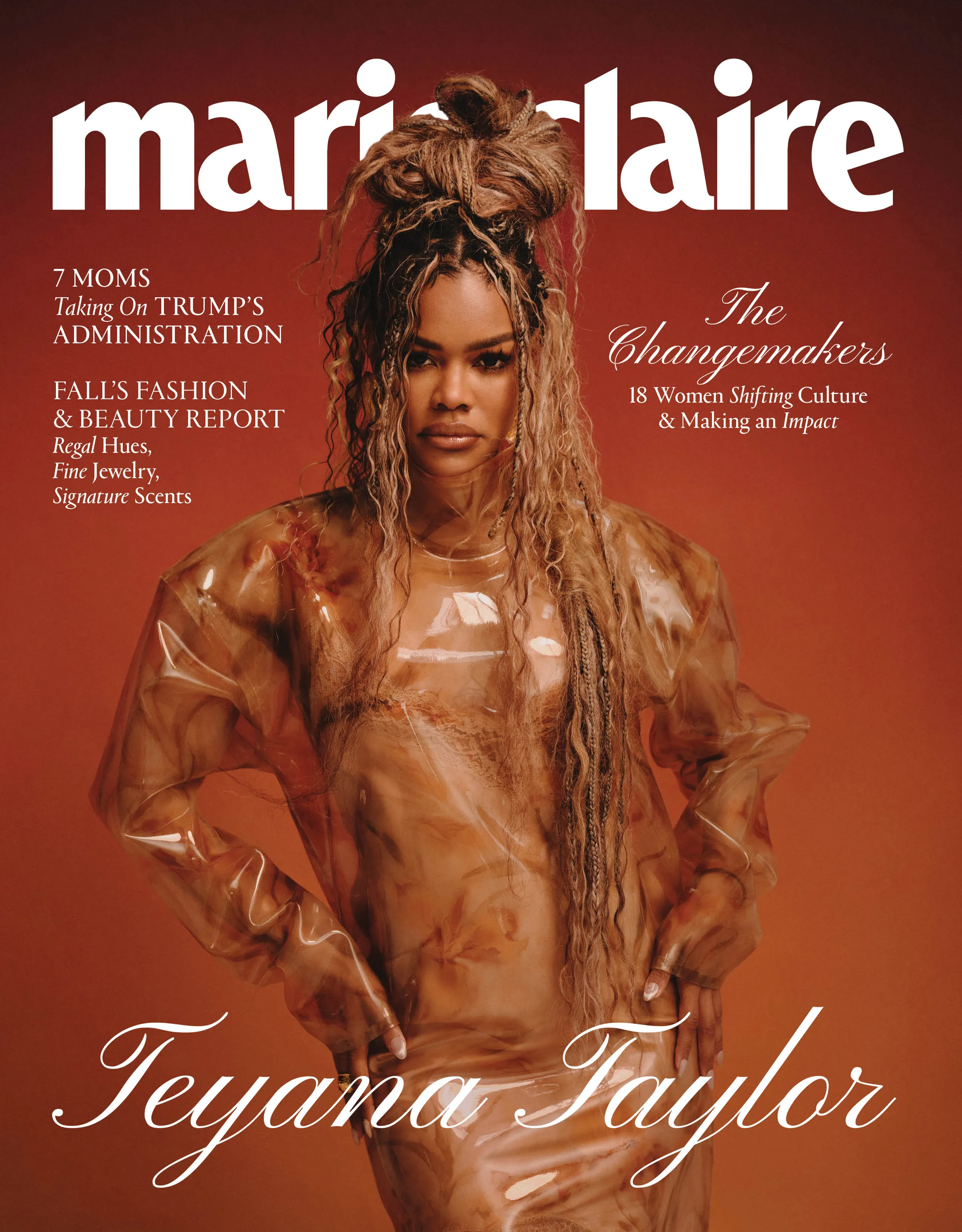

This article appears in the 2025 Changemakers Issue.

Serena Turner is a writer and producer. She recently completed two original erotic thrillers; a female-led action loosely based on Dead in the Water, the novella she co-wrote with her father; and a dramedy series inspired by Michelle Ruiz's groundbreaking article for Vogue about modern relationships. As a producer, Serena sold a scripted drama series to a streamer earlier this year (pending announcement). Notable producing projects also include a dark comedy series with Mark Gordon Pictures and Ley Line Entertainment, a romantic comedy with Burn Later Productions, a police procedural based on Tom Turner’s Palm Beach mysteries, and two documentaries -- one about the best parties of all time with XTR and a true crime with Hot Snakes Media.