Dior Photography Award Winner Cédrine Scheidig Shares Her Inspirations

"One of the things I'm trying to build through my work is this idea of opening up imaginations."

Selfportrait, 2021 “The working title for this self-portrait was: Mangrove-woman. The mangrove is a rhizomatic ecosystem found in tropical swamps. There is the idea of taking root, with the braids that fall to the ground, symbolizing this double space.”

Cédrine Scheidig belongs to a young generation the media likes to call Gen Z–a more politicized generation, free from categorization and obsessed with deconstruction. A youth who strives to create things that represent it. A generous, egalitarian generation that rejects normativity. Through her sensitive, delicate gaze, Cédrine Scheidig expresses the poetry, nostalgia, struggles and hopes of what she calls the "diasporic" youth, as it defines its own history and territory.

Can you tell us about your work process?

I like to work in a fragmentary way, creating each picture as a standalone image and them grouping them later. Each photograph is built around a gesture, something unexpected that creates meaning. An exploration, a self-discovery through my relationship with nature, grounding, taking root. I always start from my own experience, my own identity, and then I zoom out, as I look for an anchor; but finding none, I make multiples. My position is always a kind of in-between. The documentary approach feels problematic to me, because there is a whole archeology, a whole genealogy of images that come before mine, and that don't fit with me at all. I want to blow up media representations. And at the same time, my work is based on a process of extraction from reality. So this is truly where I stand, between truth and fiction, because my work articulates the diasporic identity in order to include different bodies, through this idea of double belonging, of being open to different identities.

Durag and fruit, 2021 “My still lives often center around a comb: it’s an object I’m a little obsessed with, that I like to explore constantly.”

How would you define this identity?

It is the fact of belonging to a diaspora, of what W. E. B. Du Bois called "double consciousness". A lot of words are flying around right now: diaspora, afro-descendant, or "Afropean", a new word popularized by Johnny Pitts. I like this word because it blurs boundaries, and brings together people who come from very different places, but still have a common lived experience. I grew up in a very diverse, urban Parisian suburb called Seine-Saint-Denis, and I think my art really fed on this environment. It's where I take most of my photographs, but you can't really tell, because there is a deterritorialization in my work, even though it is fully grounded in this landscape. The image of the ethnically diverse, working class, crime ridden suburb in France is extremely charged, and we end up always consuming the same images from these spaces. I'm trying to produce images that I've never really had, and that I would have liked to have: people who look like me, spaces that I find interesting.

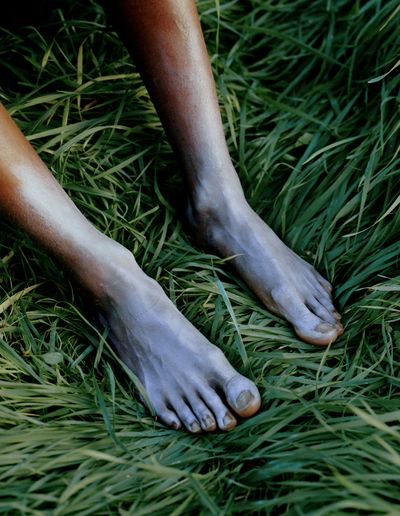

Carl, 2021 “This fragment from a body is all about grounding: feet, earth, grass... There is also something quite feminine about the color, the overall softness of the image.”

Who are your main influences?

Discovering the South African photographic scene, represented by the Arthur Walther collection, truly was a decisive moment for me: photographers like Zanele Muholi, Mimi Cherono Ng'ok, Santu Mofokeng… And also American photographers like Dawoud Bey, all these Afro-descendant creators who represented their community by themselves and for themselves. But I'm also passionate about the history of photography, for instance I love the Düsseldorf school. I also read a lot: everything Édouard Glissant has ever written, or Stuart Hall's work on afro-descendant bodies in the space of televisual representation. He's the one who theorized "the end of the notion of the essential black subject", a concept that explores the multitude of representational possibilities for black bodies, once they escape essentialism. Basically it is the equivalent of what Edward Said called "orientalism", it is about all these representations of essentialized black bodies imagined by colonial history. The "end of the notion of the essential black subject" is when this subject beaks open into an infinity of possible representations, a play on stereotypes. In my work, I look at these bodies through a deep, strong relationship to the earth and the environment, a connection to the organic, to ecology. But I'm also influenced by what is happening right now: so many young artists, young photographers from the diaspora who are emerging, opening up speech and representation. And they're not content with what they are given; they are claiming their space, as if to say: we're taking over, we'll continue to occupy this space, and we hope that others will come occupy it with us.

Robi, 2021 “I photograph a lot of male bodies, and I try to be at the opposite end from violence. The black male body has almost always been represented as aggressive, savage. I think it’s political to give them a kind of softness.”

This is a very politicized way of speaking, but your images feel poetic and soft. Isn't it a contradiction?

It's true that there is a softness in my work, something almost like affection. I mostly photograph male bodies. Some of them look like they are resting, like a call to calm. But I think it's quite political to claim that for bodies who are always working, fighting, struggling. The only female body in this series is my own, a self-portrait. I also like the idea, as a woman, of exploring the representation of the male body, of photographing it softly, like something organic, grounded in the earth.

Your work on still lives is very striking…

As a genre of photography it is quite classical, and I wanted to explore it. I always try to produce small shifts in my photographs, by inserting an object, something that will guide a specific way of reading, something that will speak of the diasporic identity. Concrete, afro combs, do-rags… small things that reference a familiar word, a space that I know and never found in classic still lives.

Comb 2 "These blocks of concrete symbolize the urbanized space of the suburb, and then there is this Afro comb – just a small gesture that integrates the whole history of the diasporic identity, within a still life image.”

How does it feel to have your images exhibited and seen on such a major stage?

It's the first time it's happened and it's very unexpected. I'm happy, because I belong to a new scene that is in development, constantly producing new representations. Most of the images that reach us are images that are imposed upon us. One of the things I'm trying to build through my work is this idea of opening up imaginations. To do that, I need my images to reach as many people as possible, and for that I need the support of big institutions. I know that some artists reject them, but that inevitably pushes them to exist at the margins, forever confined to a peripheral existence. To me, it was important to occupy the center, to say that it is possible for people like me, that we can become photographers, and produce images, and become artists; that all this isn't just for a specific kind of people. It's the same for museums: the more of us there will be in these institutions, the more open they will become to diverse sensibilities, who deserve better recognition.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

This article has been translated and originally appeared in Marie Claire France.

Sally is the Editor in Chief of Marie Claire where she oversees coverage of all the things the Marie Claire reader wants to know about, including politics, beauty, fashion, and celebs. Holmes has been with Marie Claire for five years, overseeing all content for the brand’s website and social platforms. She joined Marie Claire from ELLE.com, where she worked for four years, first as Senior Editor running all news content and finally as Executive Editor. Before that, Sally was at NYMag.com's the Cut and graduated with an English major from Boston College.