The Fight for Their Lives

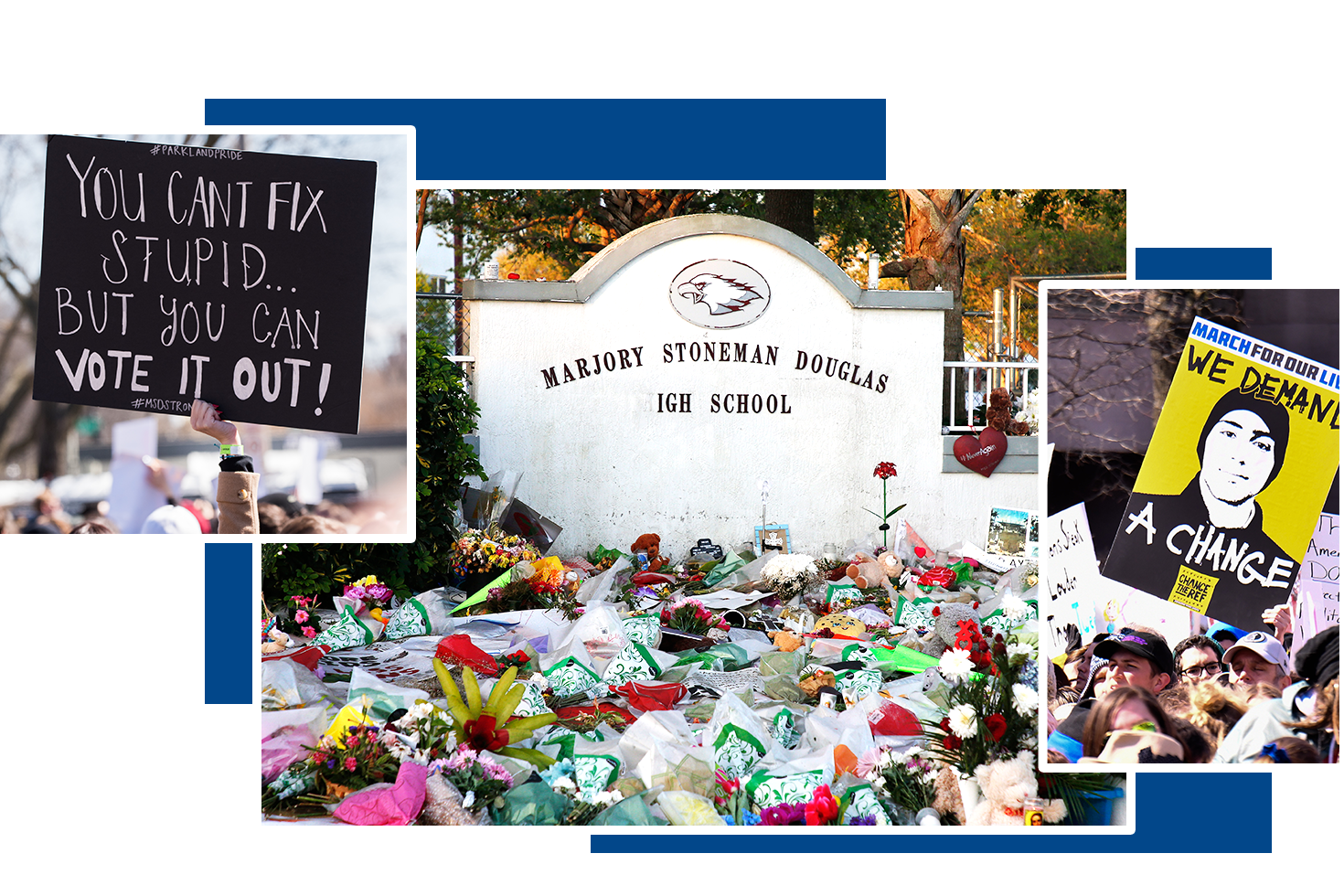

Parkland student activists Jaclyn Corin, Sarah Chadwick, and Delaney Tarr reflect on life before and after the deadliest school shooting in the U.S. since Sandy Hook—and how they're inspiring a global mission to end gun violence.

Editor's note: Around two months after this interview was conducted, another mass shooting took place, this time at Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, Texas. Ten people were killed, and another 13 were injured.

Before February 14, 2018, Sarah Chadwick, 16; Jaclyn Corin, 17; and Delaney Tarr, 17, were normal teenagers at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, attending softball practice, politics club, and student government meetings. Days after their former classmate Nikolas Cruz walked into school, pulled the fire alarm, and began shooting students and faculty—killing 17 people in six minutes—the women rose to prominence as three of the founders of the #NeverAgain movement. Just over a month later, on March 24, they stood with their fellow classmates-turned-gun-control-activists onstage in Washington, D.C., leading the largest student-led protest in U.S. history.

Here, they discuss handling the spotlight, returning to school, and how their lives have been changed.

Let’s go back to the day of the shooting. How did you process what was happening?

Jaclyn Corin: It was Valentine’s Day, and I was passing out carnations for our sale. I went into all of the classrooms that ended up being shot up. I walked out the same doors that the shooter entered 15 minutes later. I got back to my classroom five minutes before the fire alarm rang. We walked out to the bus loop and everyone started screaming. My best friend grabbed my hand and said, “Run!” I said, “What’s going on?” And she goes, “I heard gunshots.” I said, “You’re lying. It’s in your head.” I thought it was fake because we were expecting a drill.

Delaney Tarr: Teachers even said there was a possibility of firing blanks during a drill, so most of us were just like, OK, this is a really intense drill. Our teachers had been stressing the active-shooter drills a lot. It was a legitimate thought of mine: What do I do? Where would I hide? Do I just run? What is my plan to escape? I talked to my mom about it. I talked to my friends. We all had different strategies, and that’s just absurd to me. It’s not something that you should have to think about when you’re in school. You should just feel safe. And we weren’t.

Sarah Chadwick: I was coming back from the bathroom when I heard the fire alarm. I didn’t even hear the gunshots. I joined my class outside in the practice-field area. All of a sudden, there was a cop car driving toward us, telling us to evacuate, run. People were throwing their bags over, leaving their backpacks, kicking their shoes off to jump the fence. There was no other way. We ran to the gas station across the street, where my dad picked me up. The FBI and helicopters were everywhere. The whole time, I was texting my friends in a group chat. At first, they thought it was a drill too, but then the group chat went silent. That’s when my heart dropped. I have friends in that group chat who watched people die.

I’m proud of my classmates and myself for speaking out, but you have to remember why we’re doing it: all those empty desks.

DT: I was in a closet for over two hours. When the police came into the room, I didn’t know if it was them or the shooter. Those few seconds, everything stops. Silence. Nobody wanted to breathe. Then you hear, “Police,” and you think, Well, what if it’s not the police? I was texting everyone, including my parents. My phone died after I got out. My dad panicked because he couldn’t contact me. He drove on the sidewalk and was running around screaming my name because he didn’t know if I was alive or not.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

SC: Before class, I was helping a friend write an essay on gun control; now we’re fighting for it.

An estimated 800,000 people attended the March for Our Lives. How does that make you feel?

JC: It’s so surreal. I wake up every morning and remember. The attention we’re getting from celebrities, I would give all of it back to be a normal teenager again. People think we’re enjoying all of this publicity. We actually aren’t. I don’t even know how to explain how I’m feeling. I’m proud of my classmates and myself for speaking out, but you have to remember why we’re doing it: all those empty desks.

How are you giving voice to kids in places like Chicago, where some experience gun violence every day?

SC: Privilege isn’t a bad thing if you use it correctly. If you can figure out how to amplify minorities’ voices, then you’re using it for good. We’re doing this for the people who don’t have the platform because of their race or where they’re from, which is completely unfair.

DT: It sucks that people who experience gun violence every day aren’t given the platform that we’re getting because we experienced it once. But we’re trying to change that. This isn’t #NeverAgain for Stoneman Douglas, it’s #NeverAgain for everyone.

Today, the day after another school shooting, it is dress rehearsal weekend for what should have been my daughters dance recital. Rather than watching her dance, we are doing a fundraiser to raise money for Orange Ribbons For Jaime. I wish things were back to February 13th.May 19, 2018

There’s power in your age, but also your gender. How does it feel to be women at the center of this?

Jaclyn Corin brings out Martin Luther King Jr.’s granddaughter, Yolanda Renee King, for a surprise appearance at March for Our Lives."The symbolism of us holding hands is so surreal. The crowd’s screams will forever be the loudest I will ever hear in my life," says Corin. "It shows that the past is resurfacing in a different form.

JC: It’s cool that we’re empowering people in two ways: with the gun-control issue and as women. It does limit us at times, though. When we’re speaking with politicians, people are like, “Jackie, you shouldn’t go to this one because he’s against women.” It makes me so angry. I want to go off on the politicians, but some aren’t going to take me seriously because of my gender.

SC: So often in history, women have been criticized for speaking their minds. We’re showing people that young women have opinions and we’re not afraid to speak up.

DT: Girls walk up to us and say, “Because of you, I feel like I have a voice.” It’s nice to know they can look up to somebody who isn’t a man.

How do you handle the spotlight?

SC: You don’t have time for the things you used to do. We don’t hang out with our other friends.

DT: We’re under a constant eye. We don’t get to be stupid teenagers anymore. We have to be very calculated at all times. Our lives and the movement are the same right now. We don’t have a life outside of this.

JC: My dad put hurricane shutters on my windows. He’s scared someone is going to shoot me because we’re going up against the NRA.

DT: My father has been very nervous too. He sat me down and said, “I need you to know I’m freaking out about this. Your head needs to be on a swivel at all times, because it’s no longer safe.” So many people hate us with a passion.

Girls walk up to us and say, 'Because of you, I feel like I have a voice.' It’s nice to know they can look up to somebody who isn’t a man.

How is it being back at school?

DT: Everyone has different ways of coping and grieving. Some people aren’t ready to come back to school yet. I made sure to go back that first day because I wanted to be with my friends and my teachers. I’ve been to school two or three days per week. The school has been incredible. They brought in therapy dogs, grief counselors; teachers have given me their phone numbers and said, “If you ever need anything, text me. I’m here for you.” The best thing we’ve been doing is being there for each other.

JC: Teachers are very lenient. They’re pushing assignments back, not putting hard tests in the grade book. They don’t know what everyone is going through. The person next to you could be completely traumatized; they may have said goodbye to their best friend. Douglas at this point is a no-judgment zone. If a kid has to go cry in the hallway, nobody questions it.

What do you want the next generation of young people to know?

JC: We’re doing this for them. I’m doing this for my kids, for everyone I’ve met—their kids. I don’t want the next generation to fear leaving their classroom to go to the bathroom because they’re going to get shot in the head. That’s a fear of mine. It always has been—even before this. I’m afraid to walk to the car alone because I don’t know what’s going to happen, which is a gun issue and a women's issue. Those tie into each other so unfortunately well.

DT: I want every young person out there to know that they have more power than they recognize. A lot of the time teenagers have been pushed to the side, even though young people have been the frontrunners of nationwide and global changes. Just because the politicians aren’t ready to listen to you, doesn’t mean that you can’t be heard. We can make a difference now.

SC: Don’t be afraid to speak up.

Has this changed what you want to do with your lives?

DT: I wanted to study journalism. That’s changed. I do love journalism, but politics are very important to me now. I always wanted to tell stories, but now I want to change the story.

SC: I planned to major in business. Now I’m thinking politics or international relations—a complete switch.

I don’t want the next generation to fear leaving their classroom to go to the bathroom because they’re going to get shot in the head.

JC: I wanted to be a nurse anesthetist, but now I’m leaning toward politics and activism. Because we already have the platform, I don’t want to let it go to waste. We keep pushing registering to vote because it’s the easiest thing you can do to become a superhero. You can save a life, and get a greedy-ass politician out of office, just by checking a box.

DT: If I don’t continue with activism, then what was all of this for? It’s not, we do this for a while and it’s done. We will always be activists. This is our life now, and in some ways, this will shape the rest of our lives. It already has.

Rachel Epstein is the assistant editor at MarieClaire.com. She graduated from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2013.

This article originally appears in Marie Claire's June issue, on newsstands now.

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.