The Cost of Child Care Is Crushing American Families. What Will the Presidential Candidates Do About It?

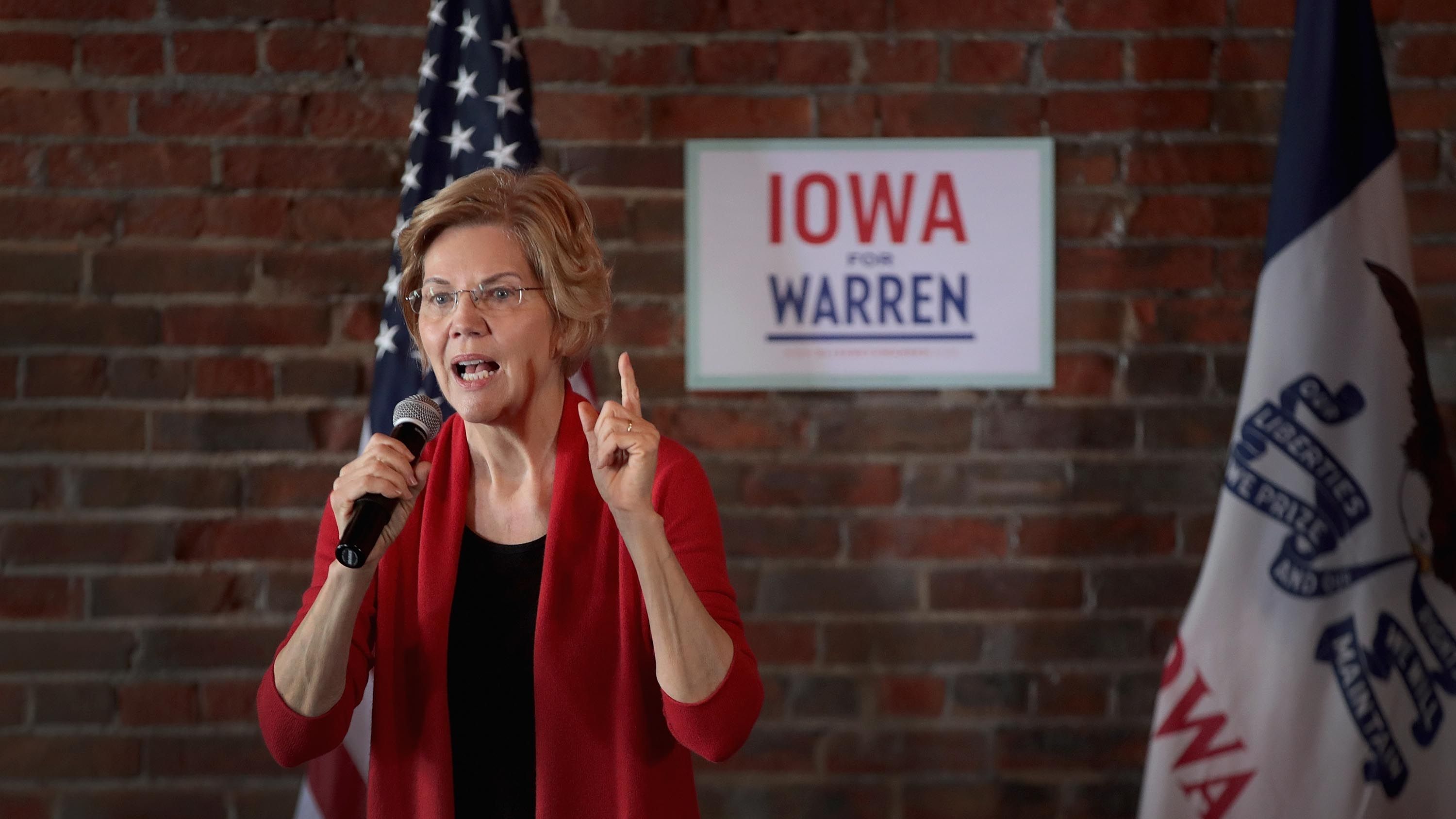

One contender—Elizabeth Warren—has proposed a bold universal child care plan.

Ashley Alcaraz gets to spend about two hours a day with her daughter, Paysen. Ten months ago, the 24-year-old x-ray technician cobbled together sick days and vacation days, plus three weeks of unpaid leave, to recover from childbirth and take care of her baby. Six weeks later, Alcaraz went back to work, and Paysen went to daycare.

Alcaraz and her boyfriend live in Tipton, Iowa, about 40 minutes’ drive away from her job in Iowa City. They’re a two-income family (her boyfriend, Spencer, does demolition for a water and fire repair company) and they’re drowning. Between rent, groceries, gas, child support for her boyfriend’s son from a previous relationship, and now $640 a month in child care for Paysen, they’re barely getting by.

“It’s terrible. We have not even enough to live on after bills…but we make it work.”

For Ashley and Spencer, “making it work” means picking up more work. Spencer has plans to take odd jobs, and Alcaraz, who works 40 hours a week at the hospital, has been taking some overtime, but that means even more time away from Paysen. So, “making it work” also means going without. “We budget,” she says, “and then sometimes, we don’t eat as much as we should. We get Paysen fed, it’s just us that don’t get enough as we should.”

One in two children in Iowa aren’t able to go to quality, affordable child care.

Alcaraz is one of many Iowa parents whose financial life has been thrown into chaos by the high cost of child care. According to the Iowa Women’s Foundation, the state is in the middle of a “child care crisis,” with low availability, high costs, and low wages crushing parents and providers alike. Thanks to a combination of strict regulations and low wages, three-quarters of Iowa children live in households where all adults work outside the home, but the state has lost 42 percent of its child care centers in the last five years. The result is that, in a state with a population of barely 3 million, about 360,000 children—or one in two—aren’t able to go to quality, affordable child care.

Democratic candidate Elizabeth Warren has proposed taxing the ultra-wealthy to fund subsidies for child care.

Perhaps that’s one reason Senator Elizabeth Warren has made affordable child care one of the most visible and detailed parts of her policy platform as she runs for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, a process in which appealing to Iowa’s voters is one of the first tests of electability.

Warren’s plan calls for a tax on the ultra-wealthy—those making more than $50 million a year—which would fund government subsidies to create and improve private child care centers, raise the wages of the people who work in them to match those of public school teachers, and defray enrollment costs for families. Families earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty line (about $50,000 for a family of four) would get free child care, and everyone else would have their child care costs capped at 7 percent of their household income. Right now, households with two incomes are spending about 11 percent nationwide, and single parents are spending a staggering 37 percent of their income, on average.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Clearly, the cost of child care is a national problem, but it’s probably not a coincidence that—when she rolled out her universal child care plan in a February 19 Medium post—Warren’s first example of a family that would benefit from it was a hypothetical single mother living in Iowa.

A post shared by Elizabeth Warren (@elizabethwarren)

A photo posted by on

Other candidates for the nomination have mentioned affordable child care as a priority. Senator Bernie Sanders has called America’s child care system “nothing less than an unmitigated disaster” and argues that “if Finland and other Nordic countries can make child care affordable and accessible to all, the United States should be able to as well,” but has yet to propose any concrete policy for achieving that goal. Senator Kamala Harris has called for a universal pre-K system; Senator Cory Booker has done the same, and, additionally, has co-sponsored a federal paid family leave bill. Senators Gillibrand and Klobuchar have backed a bill to reform the tax code to support child care centers and make the child care tax credit fully refundable, but haven’t released any detailed plans as part of their Presidential campaigns. Neither have Beto O’Rourke or Pete Buttigieg. Warren remains the only candidate to have put forward the nuts-and-bolts of solving the child care crisis.

Deb VanderGaast, a child care provider who runs the center where Alcaraz’s daughter Paysen is enrolled, says that providers are hurting almost as much as parents are. VanderGaast, who serves many families whose kids have special needs, says that one reason the state is losing child care facilities is because it’s almost impossible for people like her to retain staff members.

A child care worker in Maine reads to three charges.

“I can’t pay people a living wage,” she says, and “I’m asking them to do not only child care but really hard child care.” The workers at her center earn between $8 and $10 an hour (the state minimum wage is the federally mandated floor of $7.25 an hour). And because state regulations require a bachelor’s or associate’s degree from many early child care workers, “you’ve got people with college degrees” (and the debt that comes with them) “working for $10 an hour. How am I supposed to attract these people?” VanderGaast says she can’t raise wages without passing on the cost to parents. The result is that turnover at her center is 30 percent every year, because child care workers can’t earn enough to care for their own children.

Dawn Oliver Wiand, Executive Director of the Iowa Women’s Foundation, says the lack of affordable, high-quality child care is a huge barrier to women’s economic survival, let alone success. Without child care, it’s even harder for women to participate in the workforce. With good child care, “more women would be able to go to work and our businesses would be better off, and our communities would grow.” Wiand says that fixing the broken system will take a multi-pronged approach, because fixing one part—say, raising child care worker wages to match the regulations on their qualifications—makes all the other parts even worse. “We have to figure out how to create a public-private partnership to address it,” she says. “It’s not enough to open a few after school programs or open one new center or train a hundred new providers. It has to be all those things, and it’s going to take a lot of resources.”

With good child care, “more women would be able to go to work and our businesses would be better off.”

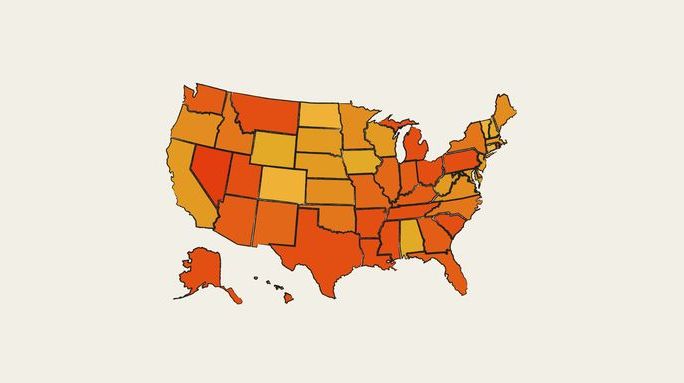

No matter which candidate wins Iowa or the presidency, it’s safe to say that relief won’t be coming soon to the hundreds of thousands of parents here, and the millions around the nation, who are being crushed by the cost of child care. And for many of them, that reality is shaping their decisions about the size of their families. In 2018 New York Times survey, the cost of child care was the number one reason people cite for having fewer children than they’d like.

That’s certainly the case for Alcaraz. She and Spencer would like to have “at least one more,” she says. But that’s simply not an option. “Not right now,” she says. “If things stay like this, we’ll never be able to.”

For more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.

RELATED STORY

Chloe Angyal is a journalist who lives in Iowa; she is the former Deputy Opinion Editor at HuffPost and a former Senior Editor at Feministing. She has written about politics and popular culture for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, The Guardian, New York magazine, Reuters, and The New Republic. Angyal has a Ph.D. in Arts and Media from the University of New South Wales.