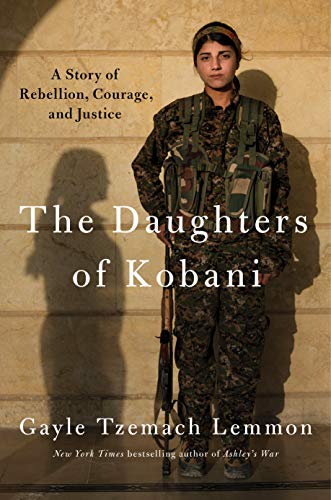

The Women Who Took on ISIS—and Won: The Daughters of Kobani

Gayle Tzemach Lemmon's new book The Daughters of Kobani tells the story of the all-female militia who defeated the Islamic State and changed women's rights in the Middle East forever. Read an exclusive excerpt here.

In 2014, extremists of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) tore through Northern Syria. They terrorized town after town, brutalizing women, leaving behind nothing but horror and destruction in their wake. They hadn't lost a battle. That is, until they reached the small town of Kobani, where the YPJ, an all-female Kurdish militia (some of whom were told as teenagers they couldn't go to school or marry who they wanted), played a key role in facing them head on—leading in battle and, remarkably, triumphed, defeating the men who enslaved women. The win in Kobani marked a crucial turning point in the fight against ISIS.

Best-selling author and adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations Gayle Tzemach Lemmon (The Dressmaker of Khair Khana; Ashley’s War) spent time on the ground with the women who stopped ISIS; her new book The Daughters of Kobani (Penguin Press, February 16) is the culmination of hundreds of hours of front-line interviews with the women who risked it all. Rigorously and respectfully reported, Lemmon's work chronicles the incredible story of this all-female force, and how their victory on the battlefield not only protected their people, but launched a new future for women everywhere. If you think the tale sounds like the plot of a TV show, you're right: Hillary Rodham Clinton and Chelsea Clinton's new production company HiddenLight Productions already nabbed the adaptation rights.

The book is a must-read for anyone who wants to better understand the Syrian conflict, feel inspired by women defying the odds to create change, or those who can appreciate courageous journalism. But don't take our word for it: Below, read the incredible introduction (exclusive to Marie Claire) of The Daughters of Kobani.

I made the trip to the Iraqi-Syrian border with some reluctance. I told myself that I had given up war—at least for a bit. I felt deeply guilty that I enjoyed the luxury of making that choice while so many I had met in the past decade and a half did not, but I was homebound and determined to stay that way.

I had spent years telling stories from and about war. My first book, The Dressmaker of Khair Khana, introduced readers to a teen‑ age girl whose living‑room business supported her family and families around her neighborhood under the Taliban. During years of desperation, it created hope. I came to love Afghanistan—the strength and resilience and courage that I saw all around me and that rarely reached Americans back home. I wanted readers to know the young women I met who risked their lives each day fighting for their future.

The Dressmaker of Khair Khana led to my next story, Ashley’s War, about a team of young soldiers recruited for an all‑female special operations team at a time when women were officially banned from ground combat. That book changed me, just as the first book had.

Once more, the upheaval of war created openings for women. I felt personally responsible for bringing this history to as many readers as I could, given the grit and the heart of the women I met in the reporting process and their valor on the battlefield in Afghanistan. The post‑9/11 conflicts had come to shape my life: I got married only a few days before heading to Afghanistan for the first round of research for Dressmaker. I found out I was pregnant with my first child while in Afghanistan two years later, when I was finishing the book. For Ashley’s War, I spent years not long after my second pregnancy immersed in the workings of the special operations community, and I was in constant touch with a Gold Star family forever changed by their daughter’s deployment. They taught me what Memorial Day actually means.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

I felt deeply proud of the work. And I also felt emotionally spent, trying to make Americans care about faraway places and people that meant so much to me personally. I was tired of living two lives, the one at home and the one immersed in war, and I thought often of that moment in the film The Hurt Locker when you return full of fervor to persuade Americans to care about their conflicts and then wind up in the grocery store, looking at stacks of cereal boxes on the shelf, and realize no one back home even remembers these wars remain under way.

I would recharge for a bit, I decided. Tell a story about the community of single moms who raised me.

And then I received a phone call that changed everything.

“Gayle, you have to see what’s happening here. I’m not joking—it’s unbelievable,” Cassie said when I picked up her call from a number I did not recognize one afternoon in early 2016. She was a member of an Army special operations team deployed to northeastern Syria, where U.S.‑backed forces were fighting the extremists of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS. This was her third deployment. She had served in Iraq in 2010 as a military police officer. Then she signed up to go to Afghanistan in 2011 as part of the Cultural Support Teams, serving alongside the Seventy‑ Fifth Ranger Regiment; she belonged to the all‑women’s team I chronicled in Ashley’s War. A few years after her Afghanistan tour, she joined Army Special Operations Forces, and that work led her to Syria and the ISIS fight.

Cassie told me that in Syria she had worked with women fighting ISIS on the front lines and that they had started a revolution for women’s rights. These women now were part of the U.S.’s partner force—the fighters the U.S. had aligned with to counter the Islamic State. These women followed the teachings of the jailed Turkish Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan, whose left‑leaning ideology of grassroots democracy insisted that women must be equal for society to truly be free. They belonged to a group called the YPJ, the Kurdish Women’s Protection Units. Cassie explained that they had been fighting for the Kurds since the beginning of the ISIS battle and well before. How they led men and women alike in the fight. How their members had blown themselves up when it looked as if ISIS fighters would capture them. How they faced none of the restrictions American women confronted when they went to war—no rules about which jobs were open to them and which remained off‑limits—and instead served as snipers and battlefield commanders and in a whole host of other frontline leadership roles. How they all shared the same messages and talking points about women’s equality and women’s rights, leading the Americans to consider them both incredibly effective leaders and ideological zealots. How they said women’s rights had to be achieved now, today; they would not wait until after the war ended to have their rights recognized. Most remarkable, Cassie said, was that they had the full respect of the men they served with in the YPG: the People’s Protection Units, which were the all‑male YPJ counterpart.

“Honestly, I’m kind of jealous of them,” Cassie said. “The men have no issue with them at all. It’s almost bizarre.

“Seriously, Gayle, these women have some incredible stories. You’ve gotta come.”

I thought about our conversation for days. It just didn’t make sense that the Middle East would be home to AK‑47‑wielding women driven to make women’s equality a reality—and that the Americans would be the ones backing them.

Gayle with PBS NewsHour interviewing Klara, a commander of the all-women’s force leading one of the front lines in Raqqa to defeat ISIS, August 2017

Syria’s civil war had begun as a peaceful protest by children at a school in 2011 and morphed into a humanitarian catastrophe that world leaders proved utterly impotent to resolve and to which regional and global powers sent proxies to fight. The Russians, the Qataris, the Iranians, the Turks, the Saudis, and the Americans— all played their roles in the history of this war. I had written about America’s tortured efforts to settle on a Syria policy back in 2013 and 2014 and about its ultimate decision to enter the ISIS fight without taking on the Syrian regime. I had traveled to Turkey on my own to interview Syrian refugees in 2015 and share their stories. The Syrian civil war by 2016 had turned from a democratic uprising to a locally led rebellion to a full‑throttle proxy war divid‑ ing those who supported the Syrian regime of Bashar al‑Assad (Russia and Iran, most notably) and those who did not (Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, to name a few). The Islamic State had taken advantage of the power vacuum and the broader civil war to make its name and take control of territory. But it was only one group in one part of the country: rebels of different stripes with differing ideologies controlled different sections of Syria. The Assad regime held the majority of the country, including the capital, Damascus, and by 2016 the second city, Aleppo, which by then the Russians had bombed into submission.

I knew far less about this all‑women’s force Cassie said I had to see. I had spotted some short pieces online and caught a CNN segment on TV, plus I saw a few photos on Twitter, which others immediately labeled “fakes” and “propaganda.” It was hard to separate the real from the fake without seeing it firsthand.

The story raised for me a whole series of questions: How had ISIS inadvertently forced the world to pay attention to an obscure militia launching a long shot of a Kurdish and women’s rights revolution in the Middle East? Does it take violence to stop violence against women? Is it possible that a far‑reaching experiment in women’s emancipation could take root on the ashes of ISIS, a group that placed women’s subjugation and enslavement right at the center of its worldview? Would real equality be possible only when women took up arms?

Geography made this particular war story even more personal. Part of my father’s family came from the Kurdish region of Iraq. He was born in Baghdad and spent his early childhood in Iraq. He became a refugee while still a child because of his religion. In fact, while traveling in northern Iraq and Syria, I carried with me a passport photo of my seven‑ or eight‑year‑old father sitting with his brothers and sisters. Alongside the picture is a stamp from the Iraqi government saying that the family had ten days to exit their own country and would never be permitted to return.

The region didn’t leave my father, even when he left it for the United States. As a girl growing up in Greenbelt, Maryland, I spent weekend afternoons with my father playing soccer and back‑ gammon, our fingernails turning red from snacking on pistachios whenever he paused his chain‑smoking of Marlboro Reds. He always found the notion of women’s equality confounding. When I was ten, my father turned to me during a heated discussion I’d started about why women in his family cooked for men and waited to eat dinner until after they served their husbands and sons. He asked me one question that expressed everything:

“Do you really think men and women are equal?”

His bafflement was entirely genuine. To him, and the society in which he and his siblings had been raised, the idea could not have sounded more absurd. So I could imagine what these young women Cassie told me about faced when it came to persuading their par‑ ents to let them pick up a weapon and head into war. What I still couldn’t imagine was how they had traveled from that mindset to this moment.

A few days later I picked up my phone and wrote to Cassie on WhatsApp. One year later, in the summer of 2017, I landed in northeastern Syria.

A young woman wearing olive‑green fatigues and a hat pulled down low to shield her from the August Raqqa sun stepped into the concrete courtyard where we had spent the past several hours waiting. To combat boredom while the afternoon stretched on, my colleagues and I there with the PBS NewsHour had climbed onto the rooftop of the abandoned house serving as a collection point for journalists hoping to witness firsthand the fight against ISIS. We had listened to the sound of gunfire and mortars targeting the Islamic State’s positions and taken turns guessing how close the front line came to where we stood. Sometimes our minders asked us to come down; they worried that our presence on the roof distracted those charged with protecting us and didn’t want to make more work for them. Otherwise, we sat around on plastic chairs in this makeshift press center in the 118‑degree heat, pleading with the Syrian forces to take us where no one with even a hint of good sense would go: the front line of the U.S.‑backed Syrian Democratic Forces’, or SDF’s, battle to retake the capital of the Islamic State.

The hat‑wearing young soldier walked toward the stoop where we sat and began speaking with one of the young men in uniform, who pointed in our direction. Sensing that our fate was the topic of discussion, our Syrian colleague, Kamiran, stepped over to join the conversation and began explaining in Kurmanci, a Kurdish dialect, that we had only today, that we really needed to get to the front line, and that we wanted the local commander running the battle to take us.

A few minutes later, the commander for whom we had waited all day at last arrived. The moment she strode through the metal gate of the house turned press pen, we all knew who she was. The rush of our male hosts to straighten the wrinkles out of their cam‑ ouflage uniforms, to stand up and outstretch their right arms to shake her hand, cemented my impression.

Klara wore a dark green, brown, and black camouflage uniform and light grey hiking boots with even lighter grey laces. Her un‑ tucked shirt draped past her waist and reached just about to the pockets of her pants, but there was nothing informal or sloppy about her. A forest‑green scarf with pink, red, and yellow flowers painted on its center and fringed tassels hanging from the edges covered her hair under the throbbing sun. She looked tan from all the days out fighting in the city’s streets. I kept noticing the dimple‑like cheek lines that appeared as she spoke. They seemed out of place somehow on a face that had weathered so much war.

She arrived late, she explained, because she had just visited the survivors of an ISIS car bomb attack against a family trying to flee the city that morning. Our team had heard the “boom” earlier, but we hadn’t known its source. Most who could flee Raqqa already had by this point, but some had stayed out of the fear of the snipers and land mines they would face while attempting to escape, not to mention the U.S.‑backed coalition airstrikes bombarding the city to force ISIS out of it. Some civilians didn’t want to leave their homes or couldn’t afford to give every last cent they had to smugglers, who earned their fortunes ferrying families from ISIS‑ held areas to liberated territory. Thousands already sat in the Au‑ gust heat waiting for the battle to end in a camp for the displaced in the town of Ain Issa.

Klara had gone to see the children who had survived the ISIS car bomb at a makeshift field hospital. Some of the kids had come out of the bombing unscathed. At least one of the parents had not been as lucky. After checking on the wounded, Klara had come to see us. Kamiran pleaded our case to her with a mix of charm and confidence, just as he had to her press office colleagues. I thought back on my earlier conversation with the SDF equivalent of a press representative, an Englishman.

“We aren’t taking anyone to the front line today,” he had said. “But what if Klara is willing to take us?” I asked.

“Well, then you can go; Klara is a commander,” he answered in a tone that made it sound as though I should know this already. Klara led, he served under her, and if she said we could go, we could go.

Now Klara listened to Kamiran argue our case and agreed to take us to the front line. We would see what it looked like to fight ISIS, block by block.

Half of our team climbed into Klara’s black HiLux pickup truck, the word toyota spelled out on its back in big white block letters. (The Taliban also loved this make of truck, as I learned in Afghanistan while writing Dressmaker.) As it turned out, the first soldier we had seen, wearing the same uniform as Klara and the same black digital watch on her right wrist, plus the hat shoved down over her eyebrows, was Klara’s driver. With her at the wheel, and Klara in the passenger seat, they set off. The only “armor” I could see protecting the pickup truck was a black scarf stretched out to cover the HiLux’s back window.

If this is what it means to be backed by the Americans, I thought as I climbed into our team minivan right behind them, I’d ask for better equipment.

Driven by our British security leader, Gary, we traversed a gut‑ ted moonscape free of people and blanketed by silence. I kept looking through the window at the carcasses of the houses we passed. Who lived in these homes, and when would they return? What did they see and survive under ISIS? And what would come next for them once Klara and her fellow fighters finished the battle?

Gayle and the PBS team interviewing Klara, a commander of the all-women’s force, not long after ISIS targeted her forces with a car bomb in August 2017

We came to a small bridge and our car slowed to a near stop.

If you’re a sniper, it must look like a bull’s‑eye is painted on the roof of our minivan, I thought. If ISIS guys want to hit us, now would be the time.

I thought of Klara and the young women who served under her. They made this drive to the front line every single day; this was their commute to work. I wondered if over time the bridge lost its power to terrify. At a certain point in war, everything can become normal.

Ten minutes later—which felt like sixty—we arrived at our destination. This was as close to the front as the SDF would take us. Before us I spotted a burnt‑out truck. Just that day it had been used as a bomb. Grey‑black streaks of smoke still poured from its charred innards. This truck‑borne explosive clearly hadn’t gone off very long ago.

Klara strode around the truck, waving her right arm here and her left arm there, pointing out the location of the attack with an unfazed air, as if she were a tour guide at a museum. She spoke of the ISIS men targeting her teammates as if she knew them. I understood why: their interaction, their proximity and mutual understanding of one another’s tactics, fighting force versus fighting force, had begun three years earlier. Our team wore body armor on our heads and torsos while Klara walked around with no armor at all, her head covered only by her green scarf.

Klara agreed to let us visit some of her troops on the way back to the press pen. At the entrance to the soldiers’ base, a house gated by black wrought iron, we stopped our convoy. Sweat dripped from my helmet onto the once white oxford I wore beneath the body armor.

As I got out of the truck and prepared to meet Klara’s forces, I realized my mistake. None of the troops we had come to see were women. And they were not Kurdish. They were young Arab men who served under Klara and the other SDF commanders.

Klara stepped out of the car and shook the men’s hands, one by one, chatting with them as she went down the row and admonish‑ ing them not to smoke cigarettes in front of the camera. She asked them about the day’s fight, talked to them about what they had seen. Some of the young men sported bandanas around their fore‑ heads and ears to block their sweat and protect them from the heat. All of them looked exhausted. “Keep up the fight,” Klara said, offering encouragement and a flash of a dimpled smile as she left.

Fifteen minutes later, we landed at the temporary base where the young women who served under Klara stayed. The women, who ranged in age from eighteen or nineteen to forty, milled around, still in their camouflage after the day’s fight, but now lounging in stocking feet rather than standing at attention in hiking boots. They sat together in their shared living room, quietly puffing on cigarettes (the camera had been put away for the moment) and drinking cups of tea: an army of women with dark hair, black digital watches, side braids, and red‑and‑pink smiley‑face socks. In a corner of the darkened room near the doorway, their weapons stood at the ready.

When we spoke, they made clear that their ambition went well beyond this sliver of Syria: they wanted to serve as a model for the region’s future, with women’s liberation a crucial element of their quest for a locally led, communal, and democratic society where people from different backgrounds lived together. This story was not only a military campaign, I realized, but also a political one: without the military victories, the political experiment could not take hold. For the young women fighting, what mattered most was long‑term political and social change. That was why they’d signed up for this war and why they were willing to die for it. They believed beating ISIS counted as simply the first step toward defeat‑ ing a mentality that said women existed only as property and as objects with which men could do whatever they wanted. Raqqa was not their destination, but only one stop in their campaign to change women’s lives and society along with it.

I could not help thinking about the parallels between these women and their enemies—not, of course, in substance, but in their commitment and their ambition. ISIS shared the grandeur and the border‑crossing scope of the YPJ’s vision—in the exact opposite way. The Islamic State’s forces believed that their work would return society to the glories of the Islamic world of the seventh century. They invoked the idea of a “caliphate” ruled by a caliph, or representative of God, with centralized power and influence. The men belonging to this radical Islamist group, which trafficked in public displays of its interpretation of Sharia law, including whippings and maimings, believed that their efforts would write a new chapter not only for Syria and Iraq, but also for the entire Middle East and well beyond. ISIS placed the subjugation, enslavement, and sale of women right at the center of its ideology.

Every day, these two dueling visions of the future—and women’s roles in it—clashed in Raqqa, as they had across northeastern Syria for more than three years. The men who enslaved women faced off against the women who promised women’s emancipation and equality. Whose revolution would carry the day?

On the drive out of Raqqa that August night in 2017, our team silent in our minivan from a mixture of heat and fatigue and re‑ leased relief, I worked to stretch my imagination around what we had seen. Never had I encountered women more confident lead‑ ing people, more comfortable with power and less apologetic about running things.

Whatever ambivalence I felt at the outset, this story mattered. Its impact would be felt well beyond one conflict, even a war with as much consequence as the Syrian civil war. The story had found me. I knew by then that when that happens, when a story grabs you, digs into your imagination, and presents you with questions you simply cannot answer, you either embrace the inevitable and get to work reporting or store it away in your mind and know it will find you and haunt you and gnaw at you regardless. I chose to get to work.

Excerpted from THE DAUGHTERS OF KOBANI by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon, on sale from Penguin Press February 16, 2021

RELATED STORY

Gayle Tzemach Lemmon is the author of the New York Times bestsellers Ashley's War and The Dressmaker of Khair Khana and an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. She regularly appears on CNN, PBS, MSNBC, and NPR, and she has spoken on national security topics at the Aspen Security Forum, Clinton Global Initiative, and TED. A graduate of Harvard Business School, she serves on the board of Mercy Corps and is a member of the Bretton Woods Committee.