Outside her ground-floor apartment in Kingston, hairstylist Jody Cooper sits on the bright blue bench that serves as her makeshift salon. The 22-year-old native Jamaican is flipping through photographs of herself—there she is a few years ago in a studded monokini, with strawberry blonde hair and blue eyeshadow, her skin several shades lighter than it is now.

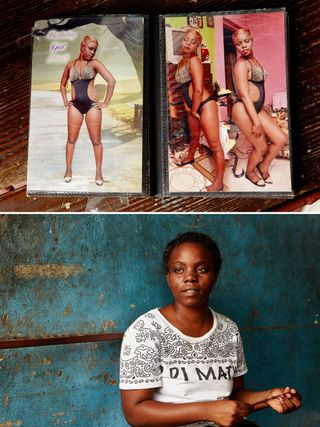

Jody Cooper bleached her skin regularly for nine years—above, she's pictured at the peak of becoming what's referred to as a browning; below, Cooper today, with her natural tone.

Cooper doesn't remember making a conscious choice to bleach her skin. Growing up, everyone around her was doing it—her school friends, her mom, her aunt. So she did it too. For nine years, she rubbed creams on her face and body, covering up with tights and long sleeves that she believed would make the bleach work better. Her goal was to transform into what Jamaicans call a "browning": a lighter-skinned black person.

As a browning, Cooper turned heads. "It's nice when the guys call after you saying, 'Browning!' and you know you born black," she says, laughing. She loved the attention; she loved fooling people into thinking she was someone a little bit different.

Payne Land—where Cooper grew up and still lives to this day—is one of the lower-income neighborhoods in the city, a collection of mid-rise cinder-block apartment buildings at Kingston's southern edge, bordered by the industrial and manufacturing district near the port. Black cultural icons Bob Marley and Marcus Garvey called this neighborhood home, too, but even still, it's light skin that's perceived by many here to be the ideal.

Left: a variety of skin-bleaching products for sale in Kingston; right: local Melissa Bryan, a practitioner of skin bleaching

"When you black in Jamaica, nobody see you," Cooper explains.

A few months ago she became a born-again Christian and, as part of that conversion, gave up bleaching. Her skin is back to what she calls "black"—a deep brown.

When you black in Jamaica, nobody see you.

Being fairer may have made her feel pretty for a while, but Cooper says her body has yet to recover from years of exposure to the harsh chemicals found in bleaching creams. She says the habit left her with a rash and blames skin bleaching for the discoloration around her eyes, which she describes as, "black like somebody sock me in the head." She's wiser to it now: "The bleaching, I don't get nothing from it," she says, looking back, "and it damage my body."

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

As Cooper speaks about her time as a "bleacher," neighbors and friends gather to weigh in. "Bleaching cut nature, it kill nature," argues Sauna Boyd. Nadia Lounds pipes up to say she "loves" the bleaching creams that have made her skin "clear."

The debate happening in this Payne Land courtyard is playing out across the country among subcultures and communities of women who, on both sides of the issue, are grappling with what beauty really means—and what sacrifices are worth making for it.

The desire for a lighter complexion is not a new phenomenon in Jamaica. It's deeply rooted in a history of slavery and colonialism, says Christopher Charles, Ph.D., a senior lecturer in political psychology at University of the West Indies who has conducted extensive research on the subject. "It's about following standards that are dictated by Eurocentrism," he says. "It's a response to hundreds of years of colonial indoctrination that has been passed down through socialization since independence."

A Jamaican street vendor mixes a batch of skin-bleaching cream.

Historically, "brown" Jamaicans were the product of relationships between black Jamaicans and white slave-owners or colonial rulers, and often received greater access to land and resources as a result of their white ancestry. Today, lighter brown skin is still read as a marker of privilege and access—class is often divided among racial lines, with wealthier and more powerful Jamaicans generally being white and brown, while poor Jamaicans are mostly black. In this context, Charles says, skin bleaching becomes a strategic choice.

"If you look at most of our advertisements, most of the things that people that would aspire towards, you see them depicted with a lighter complexioned person," says Donna Braham, M.D., a dermatologist who sees patients in Kingston and in the coastal tourist city of Ocho Rios. "That's the reality."

If you pathologize people who lighten their complexion, you ignore the racism that incites them to do it.

As recently as 2011, local newspapers reported that Jamaica's premier hospitality training agency, the Human Employment and Resource Training Trust, was receiving requests from clients for candidates who were "brownings"—particularly when looking to fill front-of-house roles. (The Trust denied this was the case.) "It's something that's there from childhood," Dr. Braham says of the implicit connection between skin tone and success. "You see that for you to be able to be anybody in life, you need to have a certain skin tone."

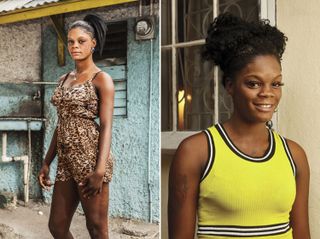

Brittany Robinson (left) during the height of her bleaching days; now 22 (right), with a more natural tone after cutting back on lightening creams.

Cooper insists she will make sure her two-year-old daughter doesn't bleach, but she knows she faces an uphill battle. Even when parents urge children to be comfortable in their own skin, the "lighter is better" message is hard to block out.

Jamaican novelist Nicole Dennis-Benn, whose book Here Comes the Sun features a teenage character who bleaches her skin, wrote an essay on how the fair complexions of most of the winners of the Miss Jamaica pageant influenced her ideas of beauty as a child in Kingston. Photos of these Miss Jamaicas were everywhere, from the supermarket to liquor stores. "Though they were strangers, our community seemed to love them more than they loved us," Dennis-Benn writes. Meanwhile, darker-skinned Jamaican women like Grace Jones—though famous internationally—were relative unknowns at home.

A several-block radius around Princess Street in downtown Kingston serves as the city's skin-bleaching shopping hub.

In a study Charles authored in the Caribbean Journal of Psychology, the top three reasons given for bleaching skin were wanting a lighter or brighter complexion, getting rid of facial imperfections, and looking beautiful. Charles points out that many people who bleach their skin, like Cooper, are rewarded for it. "People tell them that they are beautiful. People validate them," he says. "There are social benefits to having light skin, even if manufactured."

Many of the women interviewed for this story said they got compliments, were told they looked "cute," or were given more attention after they bleached their skin. A number of women said lighter skin looks better in photographs, and that those images get more views when posted on social media. The payoff is significant enough that even those who don't have a lot of disposable income will spend significant amounts on their bleaching habit: Bleaching creams and gels can cost anywhere from a dollar or two for a small tube to around $7 for a bottle. Despite the minimum wage in Jamaica equaling less than $50 per week, some women report spending $20 to $30 on creams every couple of weeks—and believe it to be a worthwhile investment.

Former skin bleacher Petal Carr

"Make man see you," says Kayalla Pierce, who lives in Kingston's Jones Town neighborhood. "Make you look pretty, like you just land from foreign." In Jamaica, having the means to get a visa and travel to "foreign" (usually the U.S., Canada, or the U.K.) connotes a higher status and privilege.

Jamaican pop culture has also perpetuated the stereotype that men find paler women more attractive. Reggae star Buju Banton created a controversy in the early '90s with his hit "Me Love Me Browning."

Petal Carr was gutted by the song. "When Buju did 'Browning' song, make me feel very bad," she says. Carr, now 52, bleached her skin for decades, starting when she was a teenager until she quit a few years ago. As a young girl, people would mock her skin color, shouting,"Blackie! You're so black! Black as a hole!" she recalls. Banton's song tapped into deep insecurities she had about her dark complexion. "It make people bleach."

Faced with criticism that he was wounding black pride, Banton released "Love Me Black Woman" shortly after afterwards, but it wasn't as big a hit. In turn, another dancehall star Nardo Ranks mocked women who use chemical lighteners in his song "Dem a Bleach," and blamed Banton for causing a run on bleaching creams.

But Charles argues that the decision to bleach is not necessarily a rejection of black culture, nor is it a result of poor self-esteem. While some people who bleach their skin may lack confidence, his research has shown that bleachers have the same rates of low self-esteem as people who don't bleach. With lighter-skinned Jamaicans clearly viewed as more attractive and favored, "the self-hate narrative as the dominant narrative just doesn't make any sense," Charles says. "When you pathologize people who lighten their complexion, you ignore the racism and colorism and the system that incites them to do this. You're actually blaming the victim."

The women interviewed for this story don't want to be seen as though they're out to radically change themselves, something that would imply self-hatred and low self-esteem. They prefer to view bleaching as a slight improvement—a superficial pick-me-up that doesn't chip away at the core of their racial identity. They seldom explicitly mention racism or colorism as a factor in choosing to bleach. Instead they use vague language, often an echo of the words the products themselves are marketed with: They want to be "brighter," "clearer," get a "different look," "tone" their skin, or "cool down" their complexion. Sometimes people who bleach are looking to get a more "matte" look, Dr. Braham says. But generally, all of these terms mean the same thing: skin that is not dark.

In Jamaica, the place to go for bleaching creams is a few-block stretch of Princess Street in downtown Kingston. Wholesale shops, many run by Chinese expats, display the products behind glass or metal grills. Outside, vendors with boxes of creams line the street.

But the market is hardly specific to this community. It's a global phenomenon worth billions of dollars, particularly in Asia. In 2016, the market for legal "skin whitening" products was $5.6 billion in China alone, according to global market research company Euromonitor International. Julia Wray, editor of the cosmetics industry magazine Soap, Perfumery & Cosmetics, says there's been a recent uptick in consumer interest in the West, too. "Brightening" and "anti-dark spot" products began to take off in the U.S. roughly six or seven years ago, Wray says; last year it was estimated to be a $600 million market.

Kingston resident Alethia Lindsay (left), whose dresser (right) is strewn with skin-bleaching products like Idole and Caro White

Skin bleaching products come to Jamaica from all over the world: There are tubes of gels with names evoking prescription medicines, like Neoprosone and Haloderm, made in Switzerland; creams like the ubiquitous Idole, made in Spain; you'll find Bio Claire and Caro White, which locals refer to as the "Abidjan" creams, after Ivory Coast's capital where they're made; there's La Bamakoise, named after the Malian city of Bamako. Some, like "Deluxe Silken," are made in Kingston, just a stone's throw away from the neighborhoods where they're so popular. Many women also use a locally made "Nadinola," sold in large buckets to street vendors who divvy it up into small bags sold for 75 cents or $1.50. Some merchants have clearly been using the products themselves; others disapprove and are just in it for the money.

In 2016, the market for legal "skin whitening" products was $5.6 billion in China alone.

Christine Greensworth, 26, has been selling the creams out of a box for more than 10 years and feels it's been very lucrative. "It sell more than food," she says. Her most popular product is Neoprosone, but she shakes her head when asked if she uses it: "Me no want brown. Me want stay black."

Seth "Marlon" McGhie is one of the vendors who sits on Princess street, selling small baggies of Nadinola. She says she makes a more-than-50-percent profit: She buys a bucket of the cream for JMD$3,000 and pockets JMD $1,700, about 13 U.S. dollars.

But many of the vendors don't want to talk to reporters. Media stories have highlighted the negative impacts of bleaching—it's bad for business.

Tyeisha Bailey, 25, says her full-body bleaching routine involves squeezing a tube of Neoprosone gel into a bottle of Idole lotion. She's been doing "rubbings"—the common expression for applying bleaching creams—of this potentially dangerous mix twice a day for a year. Several of the women interviewed for this article have even poured household bleach in a bath to try to jumpstart the lightening process.

Skin-bleacher Shanna Beckford, who has a tattoo that reads: You only live once.

This do-it-yourself approach is the reason that dermatologists in Jamaica see so many patients suffering from the side effects of misusing or overusing bleaching creams. Dr. Richard Desnoes, a dermatologist and president of the Caribbean Dermatology Association, says that without proper guidance on what strength of ingredient to use and for how long, skin lightening products can backfire—hydroquinone can cause ochronosis, a condition in which the skin actually gets darker.

This may be what happened to Carr, the Buju Banton fan. "Me used to use all kind of cream. Trust me," says Carr. She tried every new product that hit the market—the harsher, the better. She recalls that people would tell her, "'That one bad, you know! The Dolly cream bad! The Janet, it bad!' But when we say 'bad,' we mean 'good.'"

Now Carr blames those "bad" creams for her dark complexion and the thick, pockmarked skin on her cheeks. "It mash me up," she says.

Under a dermatologist's care, "the treatment would not continue indefinitely," Dr. Desnoes insists. "And a doctor would not recommend its use in an attempt to lighten the skin color of a person generally."

Skin lightening creams contain another ingredient that can have the opposite of the intended effect. A number of women interviewed for this article, including Carr's 22-year-old daughter Brittany, said they used lightening creams because they believed the products would help prevent acne. Initially, the steroids in bleaching products can smooth the skin, creating an almost baby-like texture, Dr. Braham says, but that is often short-lived. Long-term use of steroids can actually cause acne.

They hear the ill effects, but as far as many of them are concerned, this is their way of being able to get a job.

Bleaching creams with steroids can also weaken skin's elasticity, making it thinner and more fragile. Jamaican women refer to this as "busting up." This compromised skin can create dark circles under the eyes—a phenomenon that some women call "duppy bats" or "ghost bats" after the name of a local moth. Steroids may even throw the skin's equilibrium out of sync, causing fungal infections.

But the side effects are more than aesthetic. Bleaching products can cause internal damage—creams that contain ammoniated mercury are a known possible cause of kidney problems. MarieClaire.com interviewed 18 women who either currently use bleaching creams or used them in the past, and most of them reported having at least one side effect. A number said that they were well aware of the potential issues and would often stop using bleaching agents for a time to avoid them. But the chance of complications—even drastic ones—doesn't seem to be severe enough to convince bleachers to stop for good.

Jody Cooper in downtown Kingston, where she's become a born-again Christian and sworn off skin-bleaching

"They hear the ill effects, but as far as many of them are concerned, this is their way of being able to get a job," Dr. Braham says. "This is their way of being able to make more money."

Cooper admits this is true. She says that bleaching her skin was something she did to get more work; she didn't believe anyone would entrust their hair to a woman who wasn't a "browning."

"When you're in the hair industry," she explains, "you have to look the part."

But there's a balancing act here, too—Carr, who is unemployed, suspects it's been difficult to find steady work due to the visible impacts of her bleaching. Once, when she responded to a job ad, she says she didn't even get past the receptionist. "She look from head to toe and she say, 'No vacancy,'" Carr recalls. Now, she's trying to help her daughter Brittany, who's studying hospitality, avoid the same fate.

"Brittany, I warned her. I say, 'Look how it do me. You want it there that? Me old, but you young, you have everything ahead of you,'" Carr says.

Then again, she knows it's complicated. "Black is beautiful, but people make you feel a way…."

-

Sophia Bush Publicly Comes Out as Queer For the First Time in Moving Personal Essay

Sophia Bush Publicly Comes Out as Queer For the First Time in Moving Personal Essay“I finally feel like I can breathe.”

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Bella Hadid Teases Her New Brand in Three Nearly-Naked Outfits

Bella Hadid Teases Her New Brand in Three Nearly-Naked OutfitsThe supermodel gave fans a sneak-peek at her upcoming label.

By India Roby Published

-

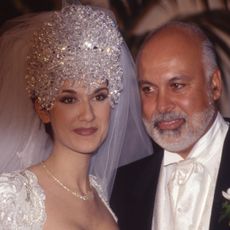

Céline Dion Says Her Epic Wedding Tiara Put Her in the Hospital

Céline Dion Says Her Epic Wedding Tiara Put Her in the Hospital"The pressure was too much."

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

The Bar Soap Boom Is Here

The Bar Soap Boom Is HereDespite endless body wash options, the art of luxury soap making hasn't slipped away.

By Sophia Vilensky Published

-

The 13 Best Products for Rosacea That Fight Redness and Irritation

The 13 Best Products for Rosacea That Fight Redness and IrritationFlare-ups are a thing of the past.

By Samantha Holender Published

-

The 32 Best Hair Growth Shampoos of 2024, According to Experts

The 32 Best Hair Growth Shampoos of 2024, According to ExpertsRapunzel hair, coming right up.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

The 20 Best Hair Masks for Damaged Hair, According to Experts and Editors

The 20 Best Hair Masks for Damaged Hair, According to Experts and EditorsHealthy strands, here we come!

By Gabrielle Ulubay Last updated

-

Selena Gomez Just Shared Her Entire Morning Skincare Routine on TikTok

Selena Gomez Just Shared Her Entire Morning Skincare Routine on TikTokThe most giving girlie.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

How Often You Should Wash Your Hair, According To Experts

How Often You Should Wash Your Hair, According To ExpertsKeep it fresh, my friends.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

The 11 Best Magnetic Lashes of 2023

The 11 Best Magnetic Lashes of 2023Go ahead and kiss your messy lash glue goodbye.

By Hana Hong Published

-

Beauty Advent Calendars Make the Perfect Holiday Gift

Beauty Advent Calendars Make the Perfect Holiday GiftThe gift that keeps on giving.

By Julia Marzovilla Last updated