Juli Briskman has always been a registered Democrat, but the most recent U.S. presidential election “sparked something in me,” she says. Each day, her anger toward President Donald Trump and his policies on immigration and the environment grew. Until, on October 28, 2017, she got her chance to show Trump how she felt.

While biking near Trump National Golf Club in Sterling, the Virginia resident spotted a line of black cars: the presidential motorcade. “I was so enraged about the image I had in my head of Trump throwing paper towels at people [in Puerto Rico]. And the fact that he’s at the golf course again! The fourth weekend,” she tells me. Just feet away from the black vans, she raised her middle finger in a gesture of defiance. The moment was immortalized by Agence France-Presse photographer Brendan Smialowski, and then tweeted out by another journalist, Voice of America White House bureau chief Steve Herman. It went viral, retweeted by over 30,000 people. Briskman, 50, “outed” herself by posting the image as her cover photo on Facebook and Twitter.

Then came the reckoning: The yoga studio where she worked part-time as an instructor began getting aggressive e-mails and bogus bad reviews on the studio’s social page. When Briskman went to work on Monday to her other job as a marketing analyst for a government contracting group called Akima, she gave HR a heads-up about her new turn as a social-media star. By Halloween, she’d been fired and escorted out of the building, her employers citing the company’s social-media policy against “obscene” content on personal sites.

For Briskman, this was not a convincing argument. She controlled the company’s social-media accounts and two months earlier saw a colleague of hers use the phrase “fucking libtard asshole” in a conversation about the Black Lives Matter movement. After her firing, she checked his LinkedIn page and saw he was still employed by Akima. “That is when I decided that I was going to talk to the media,” she explains, three weeks after her middle finger changed her life. Briskman spoke to reporters at the Huffington Post and The Washington Post, and soon a second viral story emerged—about her firing. Since then, she’s been showered with GoFundMe campaigns, job offers, and supportive petitions on MoveOn.org. She doesn’t regret her decision to flip off the president—and the support has allowed her to take some time to make a decision about the future.

For several women like Briskman, adding "activist" to their résumés has upended their professional stability.

Briskman may be the most famous corporate casualty of the resistance, though she’s not the first. Thousands of women across the country have dedicated their free time to shape the anti-Trump movement: The 2017 Women’s March rallied an estimated 4 million women in the U.S.; Indivisible, a network of local resistance groups, says that 74 percent of its e-mail list subscribers are women; and protests led by female volunteers and Senators Susan Collins (R-ME) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) torpedoed the GOP’s attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act. The 2017 Virginia elections revealed the strength of this new female-led movement, with the number of women in the state’s House of Delegates almost doubling from 17 to 28 (almost 29; a contentious race between Republican David Yancey and Democrat Shelly Simonds ended in early January after a recount and, ultimately, a random drawing). But for several women like Briskman, adding “activist” to their résumés has upended their professional stability.

The day after the November 2016 election, Saily Avelenda, a longtime New Jersey resident, sat down with her husband and told him she had to make a change. “I decided that it was my fault that the election had gone the way it did because I hadn’t done more,” she recalls. “I needed to make sure that that was never the case again.” By spring, she had split her time between work, family, and volunteering at NJ 11th For Change, an organization currently focused on challenging pro-Trump Republican Rep. Rodney Frelinghuysen.

From the start, Avelenda, 45, was careful to square her new activism with New Jersey pay-to-play laws, which restrict certain political donations, and the regulations of her employer, Lakeland Bank. As assistant general counsel and senior vice president at the firm, Avelenda did her due diligence: She consulted NJ 11th For Change’s attorney and Lakeland’s Code of Ethics policy, which states, “Each Employee shall have the opportunity to support community activities or the political process, as he or she desires,” provided it’s not done on company time and follows New Jersey state law. She was in the clear.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Still, in February, Avelenda’s boss warned that Frelinghuysen was a “friend of the bank” and told her not to mention Lakeland or display any bank paraphernalia at public events hosted by NJ 11th For Change. “I remember laughing, thinking, OK, I will strip out all the pens that have Lakeland’s name on it from my purse,” she says. By March, her boss’s warning took on an ominous tone. Avelenda’s efforts to unseat Frelinghuysen were outlined in a NPR report; shortly after, the congressman sent a campaign fundraising request to a Lakeland board member’s home address and wrote in blue pen at the bottom: “P.S. One of the ringleaders [i.e., of the opposition] works for your bank!”

The board member hand-delivered the note to Lakeland’s CEO, who then gave it to Avelenda’s boss, who presented Frelinghuysen’s letter to her. She endured a series of “disciplinary” conversations and was asked to write a statement to the bank CEO explaining her activities in precise detail. On a legal and also personal level, her employers, she says, “could never come out and say, ‘You have to drop it.’ But I had two things in my life that could not coexist.” In April, about three weeks after her boss showed her the letter, Avelenda resigned from her job at Lakeland Bank.

Caitlynn Moses, 24, had a similar experience. She managed a furniture store in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and shortly after the election, a customer mentioned the Indivisible Guide, a memo circulated by former congressional staffers on how to fight Trump’s agenda on the grassroots level. That evening, Moses looked it up at home, and something clicked. “I had gotten to the point where I was thinking to myself, I can’t just keep complaining about these things on Facebook and not do anything,” she says. Along with a friend, also a first-time activist, Moses launched Ozark Indivisible, a local resistance chapter. Two days later, it had 350 members.

RELATED STORIES

Moses has a 4-year-old daughter, works full-time, and spends her evenings taking classes toward a graduate degree in business from the University of Arkansas. She answered Facebook messages for the Ozark Indivisible group in the morning and during her hour-long break at work, stayed up late on Tuesday nights to research and post a weekly call to action, and went to events on the weekends when her husband could take care of their kid. “It’s nonstop,” she says, “because politics doesn’t really stop.”

She tried hard to balance her new commitments with her job, where she had been for five years. But her boss started to notice, and there was, she says, “some hostility about the extra time I was spending on the group.”

Meanwhile, all winter, Ozark Indivisible put pressure on Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR), one of 13 Republicans who drafted the Senate’s version of the AHCA bill, to meet with them or hold a town hall. He scheduled, then canceled, a meeting with them that February, and they protested outside his office in Springdale. A camera crew captured the protest, and it ran as part of a segment on The Rachel Maddow Show. A few days later, Cotton called Moses’ cell phone to apologize. He held a town hall later that month, and Ozark Indivisible, along with many other Arkansans, packed the auditorium. The next day, Moses’ boss pulled her aside and said, “This is a full-time job. With the amount of money I’m paying you, I need your undivided attention.” So she left. She landed at a ticket-sales company with a female boss who supported her activism, but the new job paid only half of what she had previously made.

Briskman’s, Moses’, and Avelenda’s cases are extreme but not unique. Several high-profile women in media, for instance, have been fired or suspended after speaking out against Trump: ESPN anchor Jemele Hill was suspended from ESPN after calling Trump a “white supremacist” on Twitter and defending NFL players who took a knee during the national anthem and journalist Julia Ioffe was fired from Politico for joking on Twitter about Trump-family incest. Since Avelenda left her job, she has connected with perhaps a dozen other women who felt targeted due to their political activities. To be sure, all three women work for private employers, and at the office, controversial comments or political views are not always protected by First Amendment rights. Yet women, already vulnerable professionally due to the gender pay gap and other aspects of workplace sexism, may need such protections the most.

Jean Sinzdak, associate director at the Center for American Women and Politics, says that women in America face steep obstacles to their political involvement—a greater share of housework, the expectation of being the primary parent—even without their employers stepping in. “The bigger challenge is that women don’t opt in to running for office and getting deeply involved because they just don’t have the time,” says Sinzdak. In fact, echoing Briskman’s situation, a male coworker at Avelenda’s former office was actually much more involved in politics than she was and never faced repercussions: He is a Republican New Jersey state senator.

Sometimes, workplace sexism itself can be galvanizing. In October 2016, Sameena Mustafa, a 47-year-old commercial-real-estate agent in Chicago, endured a meeting in which some colleagues discussed how Trump’s tax policy would be more favorable for their industry than Hillary Clinton’s. “I was just sitting there thinking, This is mostly a straight white male group,” she says. Mustafa was the only “broker of color” in the firm, she says, and often felt used as a token, like the time she was asked to attend a meeting with one of the firm’s principals and discovered it was with an African-American client. As an Indian-American, “I was the closest thing to an African-American woman they had,” she says.

After the election, she began exploring a run for Congress in Illinois’ 5th District, a demanding process that has included trainings across the country and regular meetings with grassroots community organizers. To make time, she cut her hours and began working from home. “You can storm off and say, ‘You’re a racist, sexist pig.’ [Or] think to yourself, I’m going to take this flexibility and use it to my advantage.” In August, she announced her candidacy and goes up against Democratic incumbent Mike Quigley in the March 20 Illinois primary.

Out of financial necessity, Moses recently went back to her old job. She told her boss in advance that she had to continue her work for Indivisible. She says they’ve developed an uneasy “don’t ask, don’t tell” arrangement. “It’s hard to be an activist, I guess, is what I’ve learned from all of this,” Moses says. But she doesn’t regret her decisions. “I don’t see any way that I could stop, because if I stop, who’s going to do it? And it has to be done.”

"It's hard to be an activist, I guess, is what I've learned from all this. I don't see any way that I could stop, because if I stop, who's going to do it? And it has to be done." — Caitlynn Moses

Avelenda, meanwhile, has not found a new job. Since she began speaking to the press about Frelinghuysen’s letter, she says she’s been blacklisted in the New Jersey banking community. However, her "full-time unpaid role" as an activist has brought Avelenda tremendous satisfaction. In January, Freylinghuysen announced that he would not seek re-election in 2018, part of a wave of Congressional Republicans with plans to retire this year. Avelenda was thrilled by the news. "This is the culmination of a year of hard work by NJ 11th for Change," she tells me. "We brought the Congressman's record into the light, and we forced him to be accountable. He finally got the message."

Going from losing her job to helping the man responsible lose his, she says, was a major victory, regardless of her own employment status. "THIS is what resistance looks like."

-

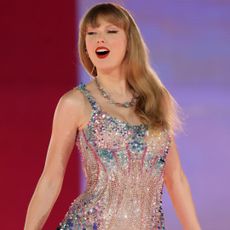

All the Cult-Favorite Activewear in Taylor Swift's Eras Tour Rehearsal 'Fits

All the Cult-Favorite Activewear in Taylor Swift's Eras Tour Rehearsal 'FitsThese pieces earned my immediate "Add to Cart."

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

Simone Biles Has a Message For People Telling Her to “Leave” Her Husband

Simone Biles Has a Message For People Telling Her to “Leave” Her HusbandThe most decorated gymnast of all time has spoken...and would rather you not.

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

How the Twisty Finale of 'Fallout' Alters Its World Forever—and Sets Up Season 2

How the Twisty Finale of 'Fallout' Alters Its World Forever—and Sets Up Season 2Once more into the Wasteland.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

Almost Famous

Almost FamousHalf of the Shondaland dream team, the woman whose work brings 'Bridgerton' to life, is one of the most influential producers in Hollywood. And she’s ready for everyone to know it.

By Jessica M. Goldstein Published

-

Payal Kadakia Is Finally Sharing Her Secret Sauce to Success

Payal Kadakia Is Finally Sharing Her Secret Sauce to SuccessIn her new book, LifePass, the ClassPass founder gives you the tools to write your own success story.

By Neha Prakash Published

-

The Power Issue

The Power IssueOur November issue is all about power—having it, embracing it, and dressing for it.

By Marie Claire Editors Published

-

J. Smith-Cameron Is in Control

J. Smith-Cameron Is in ControlShe’s Logan Roy’s right hand. She’s Roman’s ‘mommy girlfriend.’ And she’s a fan favorite. Here, the Succession star takes us behind the scenes of Gerri’s boardroom power plays.

By Jessica M. Goldstein Published

-

What Makes an Olympic Moment?

What Makes an Olympic Moment?In the past it meant overcoming struggle...and winning. But why must athletes suffer to be inspiring?

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

'The Other Black Girl' Gets Real About Racism in the Workplace

'The Other Black Girl' Gets Real About Racism in the Workplace"It really hits home how many spaces don’t allow Black women to really show up as their authentic selves."

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New Eyes

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New EyesThe true crime expert and daughter of the Happy Face Killer opens up to Marie Claire about destigmatizing the label of 'criminal's kid.'

By Maria Ricapito Published

-

Simone Biles on Her GOAT Leotard: Don't Be Ashamed of Being Great

Simone Biles on Her GOAT Leotard: Don't Be Ashamed of Being GreatThe world's greatest gymnast shares how she takes care of her mental health, the road to Tokyo, and the story behind her epic new leotard style.

By Megan DiTrolio Published