1 Writer and 100+ Reporters: The Making of the 'TIME' 9/11 Cover Story

Nancy Gibbs reflects on writing the cover story for the award-winning black-bordered special issue many people still have saved today.

Click here to read the complete "Reporting in Real Time" series

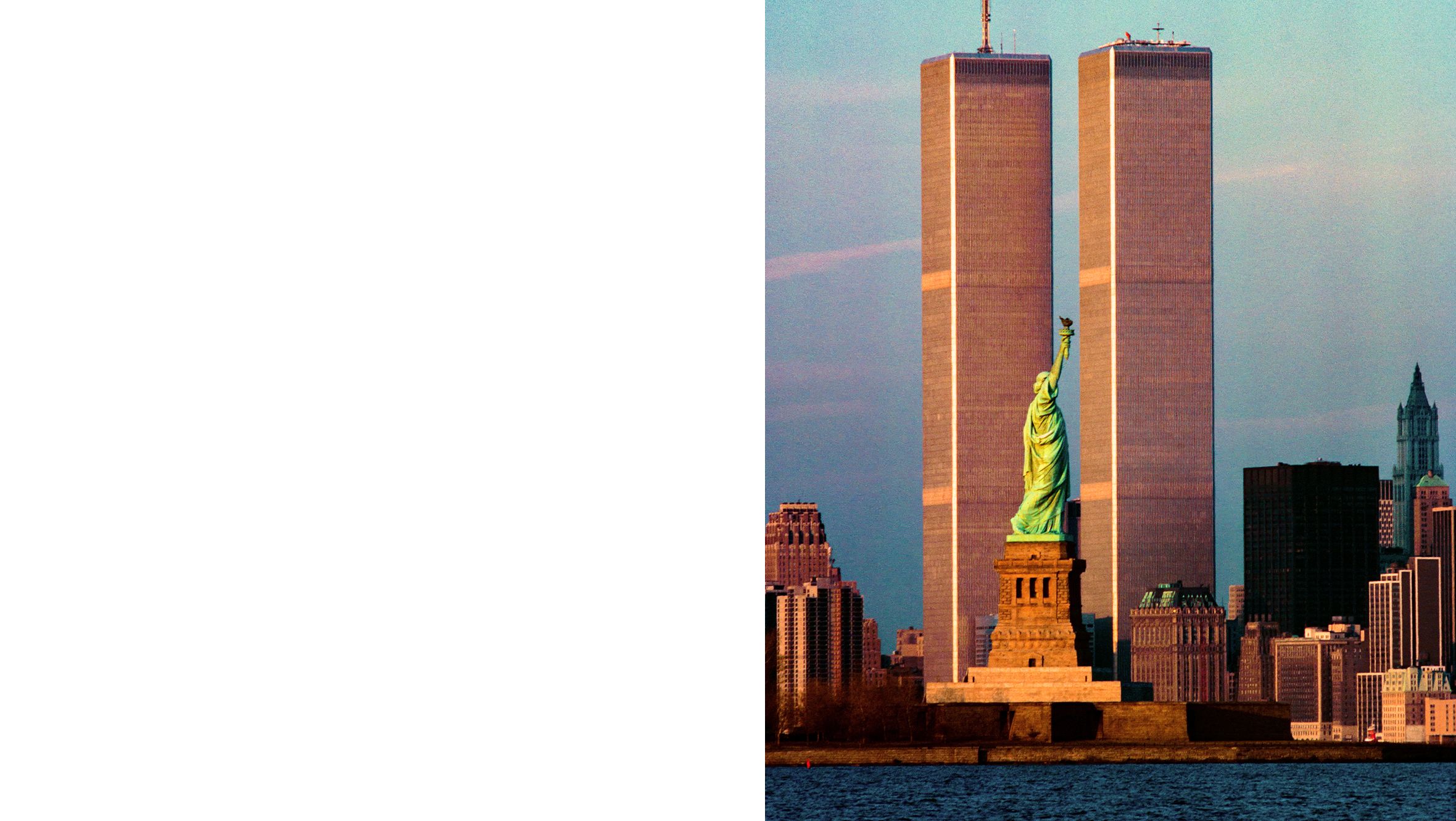

Twenty years ago, September 11, 2001 became—and will forever be—one of the biggest and most important news days in American history. As we remember the events that unfolded and honor the nearly 3,000 lives lost, Marie Claire asked five women journalists to reflect on covering the 9/11 attacks in real time and the lessons that can be learned today. Here, former TIME magazine senior editor Nancy Gibbs, who currently serves as an editor-at-large, recounts writing the magazine's award-winning cover story, "If You Want to Humble an Empire," in less than 48 hours. Go behind the scenes of her feature below, then read the rest of the journalists' stories here.

I was living in Bronxville, New York, on the "writer's block" (it was heavily populated by journalists at networks and newspapers). Ordinarily, I would have [already] been heading into Midtown [Manhattan] to the Time & Life building [on the morning of September 11, 2001], but my husband had broken a bone in his hand that weekend and I was taking him to see the doctor, so we were both at home when the phone rang. It was Michael Duffy, TIME's bureau chief in Washington. I picked up the phone and he said, "Turn on the TV." It wasn't "Hello," it wasn't "Good morning." It was just "Turn on the TV." That was probably around nine o'clock, 9:15—at whatever point the coverage had switched so that whatever [channel] you were watching, you were now watching the towers.

At around 10:30 a.m., Jim Kelly [the managing editor of TIME] called me after coming out of meetings figuring out what to do. At the time, the magazine closed on Friday night. We could still update it into Saturday and print it on Sunday to be on newsstands Sunday night/Monday morning. But, of course, it's Tuesday morning. [Jim] had explored with other Time Inc. magazines, especially People, about whether we could [switch with them to] get TIME on the printing presses in advance of our normal print run. And he told me if we can finish everything by six o'clock [the next] night, we could publish a special issue that would be [published] on Thursday, [September 13 and on newsstands Friday, September 14]. So I said, "Just tell me which story you want me to do."

Nancy Gibbs

Ordinarily, if you're going to try to do a whole magazine in 24 hours instead of seven days, the logical thing would be to split it up and one person writes about New York and one person writes about the attack on the Pentagon and one would look at how government agencies were responding and who might have done this. You would just divide it up into 10 pieces in a parallel process. Instead he says, "Well, I only want one story and everyone else is going to go report it and file to you. I just want you to tell the story of today. Think of it as a time capsule. We don't know who did this. We don't know what is going to happen five days or five years from now because of this. Just tell me the story of today." It was a test of speed as much as anything else. And he had no safety net. If I didn't get words on the page, he was going to have nothing other than a lot of pictures.

Well over 100 people were [reporting for me]. Robert Hughes, a brilliant art critic, lived in lower Manhattan and sent me a file on the sights and sounds. James Nachtwey, arguably the world's greatest living war photographer, who probably at that time spent [only] a dozen nights a year in his apartment in New York, happened to be in Manhattan and grabbed his cameras and ran downtown. He shot a lot of photos in that issue. It was just an incredible coincidence that when the war was actually happening here that he was there to photograph it. Jay Carney was our White House correspondent at the time and had pool duty [(in which a select number of reporters travel with the president)] on Air Force One, so he was with President George W. Bush as they flew to multiple air force bases around the country before getting back to Washington at the end of the day. He did not really contact us until [the pool reporters] were allowed to for security reasons, but I had him reporting directly from being with the president.

It was a test of speed as much as anything else. And he had no safety net. If I didn't get words on the page then he was going to have nothing other than a lot of pictures.

Everyone in the Washington Bureau fanned out to the Pentagon and the intelligence agencies. And everyone in New York fanned out to head downtown, head to the hospitals, head to city hall, police departments. Then correspondents around the country and in major world capitals started reporting on responses of foreign government and communities and leaders around the country. It was a complete all-hands. Normally we would have a formal system whereby people sent files into a central information management system; everyone just emailed me. I probably had a thousand emails. It was the writing equivalent of putting a jigsaw puzzle together. Everyone had a different piece of the puzzle.

The way I approached it as a matter of writing was that as each new piece of information came in, I made a guess of where in the story it's going to belong. The same way when you're doing a jigsaw puzzle you put all the blue pieces together because that's going to be the sky. So trying to arrange each detail in at least the rough order that I thought I would need it and, if I had five different people saying a version of the same thing, picking the best, and saving the other four in my sort of outtake basket. As the day went on, more and more reporting came in. I was also watching TV and monitoring websites of multiple news organizations—not just the major national ones, but the local ones as well. I was able to hear when [then-New York Mayor Rudy] Giuliani spoke or when White House officials spoke.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

I have two daughters; my older one was a first grader at a private school in Westchester, where a relative of President Bush was in her class. My husband went and picked her up from school and brought her home. So I had the good fortune of knowing that my husband and daughters were safe. There I was out in the leafy green suburbs while the city I grew up in was smelling of every imaginable, horrible, deathly smell. It was very strange to be in a place that felt so peaceful and safe when suddenly everyone was dealing with the fact that safety is an illusion.

I had a [home] office that was a converted sleeping porch with windows on three sides and a 20-foot high vaulted ceiling, where all of my stray thoughts could just float up and get trapped. I think my husband made many pots of coffee. He just checked in like, "What do you need? Do you need fuel? Do you need water?" People at work were trying to make sure I was getting what I needed and also not bother me.

I honestly don't remember the act of writing. I feel like we all wrote [the story] together. I can tell you right now that I think the strongest line in the story, I did not write. Josh Tyrangiel, who would go on to become the editor of Businessweek and then go over to Vice and HBO, wrote it. He sent me the line, "On a normal day, we value heroism because it is uncommon. On Sept. 11, we valued heroism because it was everywhere." The insights, how people were processing, what we were all living through...I was just trying to do justice to what they were seeing and learning.

A firefighter prays after the Twin Towers collapse on September 11, 2001.

The piece was supposed to be due at 6 p.m. Wednesday, and at about noon, Jim Kelly calls and says, "We have found that we can print more [copies] sooner if we can move up the deadline, so can you send the story now?" Like, what makes you think I have anything to send? And he's calculating how many hours it will take. He knows this is going to be a long story and it's about 10,000 words to edit, top edit, copy edit, lay it out, do all of the processing. And then he said, "Well, I'll tell you what, if you want to send it in chapters, I will have multiple people on this end editing, fact-checking, copy-editing it simultaneously."

I had this vision that he had a bunch of workstations where an editor would pull up a chapter and be line editing while the copy editor over one shoulder is saying, "That should be 'which' not 'that,'" and the fact checker over the other shoulder is saying, "I think that should be 1,457, not 1,459." So I started sending in chunks of copy and hoping that when they reassembled it, that it would all be in the right order. And at about six o'clock that night we met the new moved-up deadline to ship everything off. Jim called me one last time [before the issue went to the printer] and he said, "Story's amazing. I've only had one question raised from Norm [Pearlstine, Editor-in-Chief of Time Inc.]." He said, "Norm just took issue with one phrase up in the first paragraph and wonders if you'd be comfortable adding this word," and I'm like, "Yes, that is fine. I am happy to add that word. Thank you. That clarifies it."

Jim called me again at about 6 a.m. Thursday morning and he said, "I want you to know that a messenger just delivered the first copies to me and I am holding it in my hand. However long you and I stay in this business, I don't think we're ever going to be prouder of anything that we've done."

I was not back in the [Time & Life] building very much that fall. I mainly worked from home, and I think partly because Midtown Manhattan was a very stressful place to be. [The leadership] recognized that if I was going to be completely immersed in this topic, it was easier for me to do it looking out my windows at trees and children playing. I might go in a day here, a day there. I remember the feeling of dread driving into the city and of relief driving out. So many working mothers I knew could tell you their escape plan. They had thought through, what am I going to do if the bridges and tunnels get closed? Who picks up my kids from school? That kind of contingency planning was just part and parcel of working in a skyscraper during that fall.

Winning the National Magazine Award [for the single-topic issue category the following year] was bittersweet. One, because it's the story you wish you'd never had to write and, two, because it has my name on it, I got credited for astounding work by a lot of other people, starting with Jim and his incredible leadership. And then the amazing, heroic reporting effort that dozens and dozens of my colleagues did. I wish every award that story won could have listed the entire masthead of TIME because that would have been a more accurate distribution of the credit.

A note Gibbs received from Jim Kelly "who made extraordinary leadership decisions that day." "He emailed me about getting a bunch of us together for dinner on the 20th anniversary," says Gibbs. "It still remains part of our lives as New Yorkers, certainly, and as Americans, certainly, and as journalists professionally.

The way TIME journalism had worked for decades was that, very often, you would have a team of people working on a story together and doing a division of labor in which one person is responsible for the writing and other people for the reporting. We had those muscles fully built, and these were all people I had worked with. The Washington people especially were just world-class. But I also remember thinking that some of the best reporting I got from New York came from some of our most junior people who just grabbed their notebooks and ran downtown and had the ability to get people to talk to them even as they were obviously traumatized. The eye for detail in trying to paint a picture for me of what something looked like or sounded like or felt like.

Ultimately, I strongly believe that human beings need stories the same way we need air and food and water. It's how we make sense of things. And I think it's the responsibility of journalists in the face of events like [9/11] to just try to find the story and the characters whose actions have meaning. This story had so many characters in it [whose] meaning was of sacrifice and of kindness and of courage. And those are the stories that sustain us. As horrific and harrowing as that day was, I keep coming back to heroism in unexpected places. That is what lingers with me 20 years later.

RELATED STORY

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.