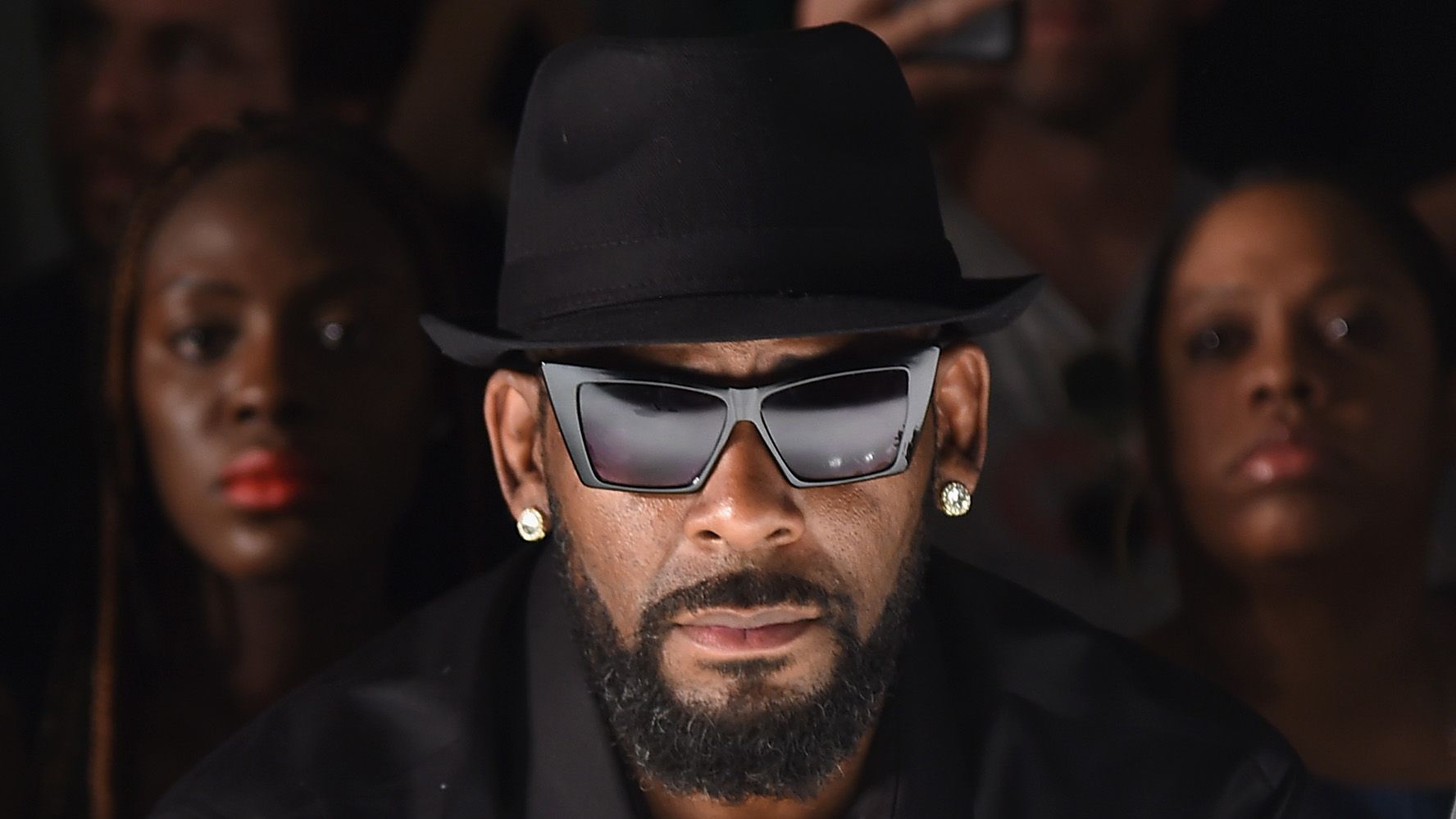

R. Kelly Docuseries Reminds Us That Not All Stories of Sexual Assault Are Treated Equally

Especially when they’re told by black women.

This past weekend, I subjected myself to six hours of the raw, triggering, and traumatizing docuseries that is Surviving R. Kelly. It originally aired on Lifetime January 3–5, but just from the trailers I knew I'd need the weekend to process it. The series contains countless testimonies from alleged survivors, family, and friends—many of whom accuse R. Kelly of predatory behavior, leading a sex cult, sexual assault, rape, and other lewd and upsetting acts. (To be clear, Kelly has not been convicted of any wrongdoing and has repeatedly denied allegations of misconduct. He did not comment for the series.)

When I began the six-part series, I thought I would be able to have a lively discussion with my boyfriend afterward about what we'd just seen. But by the time I actually closed my computer, I found myself speechless. When I could finally form words, I summed up what I had watched this way:

The lives of Black girls do not matter. Not to a majority of society, not to the law, and especially not to R. Kelly.

Kelly's story and that of his accusers is cut from the same cloth as many in the #MeToo movement: Powerful men who've been accused of wielding their power to sexually exploit and abuse women. But there's a glaring difference between so many of those cases and the case of R. Kelly, and that's the race of the accusers.

What we found is that adults see Black girls as less innocent and less in need of protection as white girls of the same age.

Let me be clear: All accusers of sexual assault deserve to be heard, they deserve a fair trial, and they deserve a conviction if their allegations are true. That’s completely regardless of race. But it's naive to pretend that race doesn't play a factor in how our society brings justice to the accused, especially when it comes to Black bodies.

In 2017, Georgetown Law published a study titled “Girlhood Interrupted” that assesses the "adultification" and scale of innocence for a Black girl. “What we found is that adults see Black girls as less innocent and less in need of protection as white girls of the same age,” says Rebecca Epstein, lead author of the report. Systemically, white women are seen as deserving of protection, whereas Black women are not. This statistic leaves Black girls and women feeling S.O.L.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

In the 2o-plus years since R. Kelly’s first lawsuit involving sexual assault was settled for $250,000, the allegations against him have stacked up: Kelly married his protege, Aaliyah, when she was just 15 (in the series a former Kelly aide says that he obtained forged documents to facilitate the marriage); he's been accused of committing underage rape on film and other sexual misconduct. Why, after two decades of rumors, stories, and accusations haven't there been more investigations, more arrests, more court cases? Why wasn't he immediately rebuked and disgraced, dropped from his label with records and tours cancelled, the way other men of the #MeToo movement swiftly were? In my estimation, it's because all of his victims were Black, not white.

The dismissal of Black victims—whether subconscious or not—is directly linked to society's history of hypersexualizing the black body. The Georgetown study states: “Caricatures of Black femininity are often deposited into distinct chambers of our public consciousness, narrowly defining Black female identity and movement according to the stereotypes described by Pauli Murray as ‘female dominance’ on the one hand and loose morals on the other.”

This juxtaposition that's created for us of being dominant, strong, and independent, yet sexually promiscuous creates a loophole for society and the legal system to pass through whereby black girls and women are simply overlooked when it comes to being considered victims of predation. Don't get me wrong, black women are resilient and strong—it's what I love most about the matriarchy of women that raised me—but we're not strong enough to defeat decades-long predatory behavior on our own.

Meanwhile, R. Kelly remains free to pursue his music career, his talent often brought up in direct response to accusations.

In 2002, a video began to circulate in which, according to sources in the docuseries, R. Kelly is shown having sex with a teenager whom he urinates on. It is perhaps his most infamous alleged sex crime. The 14-year-old Black girl in the video was said to be a relative of the singer Sparkle, whom R. Kelly was a producer of at the time.

Following the viral video distribution, Kelly was arrested on 21 counts of child pornography. The artist posted bail and pleaded not guilty, denying any and all involvement in the tape. His actual trial on some of those charges did not occur until 2008 and, during the six-year period between, he released some of his biggest chart-toppers, including the album Chocolate Factory and the hit single, “Ignition (Remix).” He was ultimately acquitted.

Support for an artist's work and ensuing continued fame enables predators to skirt the law.

Fans were torn during the trial, with those who were paying attention falling into roughly two camps. The group now united under the hashtag #MuteRKelly was vocal, campaigning to have R. Kelly’s concerts cancelled and his songs removed from radio.

The second camp is of the mindset, essentially, that people should separate the man from the music. This faction is highly problematic and, I'd say, responsible for the lack of outrage over the two decades'–worth of sexual assault allegations from Black women and girls against the singer. The "man vs. the music" argument suggests that society should separate the artist from his art, that his conduct should not have any bearing on the enjoyment a fan receives from experiencing his work. "I'm an R. Kelly fan. I'm here for the music and nothing else," a woman shown waiting in line for Kelly's concert says. But support for an artist's work and ensuing continued fame enables predators to skirt the law. It allows fans to turn a blind eye to the stories of Black women. To rely on that same thinking that's rooted in the "adultification" of Black girls: that black women don't need to be protected, that some of them likely brought this upon themselves, considering their natural promiscuity.

Would society as whole have been more outraged, boycotting Kelly's concerts and refusing to buy his music if it was a white girl in the sex tape? Recent history and not-so-recent history, implies yes.

But something about this documentary made me feel hopeful about the future. Despite the lingering support for Kelly, the show is proving that perhaps he's no longer untouchable. The women in the documentary deserve to be heard, and—based off the conversations sparked on Twitter, at the dinner table, and in Slack channels at work—I’m not the only person who thinks so.

Because, though this documentary reminded us that Black girls' lives haven't mattered, its mere existence proves they might be starting to. On Tuesday, the Cook County State's Attorney's office held a press conference asking anyone who may be a victim of R. Kelly's to come forward. UltraViolent, a women’s rights advocacy group, has commissioned a banner to fly over Sony Music records that reads, “RCA/Sony: Drop Sexual Predator R. Kelly.” And an emergency motion was filed to enter Kelly’s Chicago studio, which according to the docuseries, was the location of many of the alleged events.

It looks like the tide is finally changing. Society and the legal system are ready to listen to black women. Here's to hoping we’re actually heard

RELATED STORY

Alexis Jones is an assistant editor at Women's Health where she writes across several verticals on WomensHealthmag.com, including life, health, sex and love, relationships and fitness, while also contributing to the print magazine. She has a master’s degree in journalism from Syracuse University, lives in Brooklyn, and proudly detests avocados.