Writer-Director Lorene Scafaria on the Making of Hustlers

Including the mundanity of strip clubs, intense female friendships, and the gamechanger that is Jennifer Lopez.

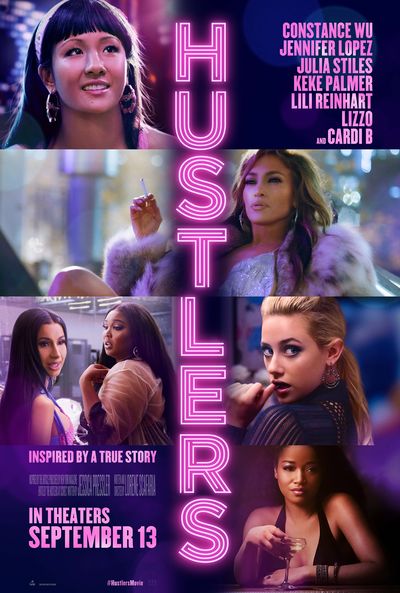

Whenever I try to describe Hustlers, it sounds like I’m doing some off-brand Stefon bit. But the thing is, this movie does have everything: an unreal-except-it-actually-happened true crime at its center; a searing, brutal acknowledgment of the horror show of American capitalism; the just-right soundtrack and wardrobe (Juicy tracksuits!) for an early aughts period piece; the pristine CLACK of stripper heels smacking the stage as Jennifer Lopez does for pole-dancing what Simone Biles has done for gymnastics.

It’s a movie centered on the complicated, passionate, mercurial relationships and power dynamics among female friends, a film in which men are so laughably secondary—a smattering of rude bosses, hapless marks, and disappointing boyfriends—that I genuinely forget all of their characters’ names. It is a movie about strippers, set largely in strip clubs, that never feels leering or gross.

Writer-director Lorene Scafaria is overwhelmed by the response to the movie, which only wrapped a week before it premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival (just six days before it came out to the world). “I’ve never had a film of mine make such a big splash,” she says. “It was all really a little too soon, to be putting it out there.” Scafaria is fascinated by people’s “visceral reaction” to this movie about strippers and the Wall Street bros they sweet-talked, drugged, and robbed. She knows these aren’t the kind of characters who get to be protagonists; she knows what they did is—depending on your take—understandable or reprehensible or both. For all these reasons and more the film is quickly becoming iconic; here's what it was like to make it.

Marie Claire: I realized as I was watching Hustlers that I’ve seen women, in various states of undress, in movies my entire life. So many TV shows and movies feature scenes in strip clubs, but it’s rarely if ever from the point of view of those women. They’re just somebody else’s set dressing.

Lorene Scafaria: I was so excited to capture what’s really mundane about a strip club, and plain and human about it, as anything else.

When asked how I was going to approach the nudity of it, I thought well, without shame, obviously. The locker room is reminiscent of my bathroom and hanging out with my friends getting ready to go out for the night and psyching each other up. That, for me, was just a place to really witness the sisterhood and the camaraderie, and get to see nudity as it is, which is incredibly boring and regular.

Then to watch Ramona [played by Jennifer Lopez] wield that power [of her body] against people and use it for her own gain was equally exciting to me. I was interested in exploring the female body as it has been thought of in the past and, in a way, as a celebration of it, and an exploration of it, and as a means to talk about our broken system.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MC: I was really struck by how you filmed women stripping in a way that does feel real and sexy but not gratuitous or grimy or degrading. Can you talk about the technical choices you made to achieve that? I’ve described it to people as being like watching athletes in a training montage.

LS: Yes! That was how Todd Banhazi [the director of photography] and I spoke about the movie as a whole. Certainly a scene like Ramona’s big dance number, we wanted to shoot it like a sports movie and highlight the athleticism of it and the strength of it, and how much it can be a team sport or a solo sport, depending on how you’re doing it. It starts as a solo sport for Destiny [played by Constance Wu], until she meets Ramona, and gets to experience it as a team sport with that camaraderie.

It was always there on the page, even in the script, it describes them as football players leaving the tunnel when they’re walking out onto the floor. We applied that theme of control to the camera as well, which allowed us to stay in Destiny’s point of view, and watch Destiny seeing Ramona for the first time, and see the audience being controlled by Ramona, but also see Ramona in control.

Jennifer Lopez and Director Lorene Scafaria (right) behind the scenes on the set of Hustlers.

MC: Let’s talk about Ramona’s big entrance scene, that incredible dance sequence. You wrote this script before you cast the movie, yes? I imagine you’ve got in brackets “[Ramona strips]” and that’s all there is. But then you cast Jennifer Lopez and a whole tier of possibilities opens up. What was the evolution of that scene?

LS: I believe on the page I wrote “Ramona does one final flourish, and then we watch her walk across the room.” And it was more about seeing her owning the room and the reaction to her as she glides through it, taking money. So Destiny would still get to watch Ramona in action and wonder, how does she do it? How can I learn from that?

But when you cast Jennifer Lopez, you’re going to get a lot more than one final flourish! So it was incredibly exciting for me, that we had someone with incredible dance ability, and someone so willing to do the work and the training that was required for her to do that routine. Because even though she dances every day and is obviously in better shape than any human person, even Jennifer said that what was required for the pole was just muscles she didn’t know she had. So it was incredibly exciting to get to break that scene out and really make a moment of it.

I knew it was going to be an exciting entrance for a character either way, but I never imagined that it could be what it was until Jennifer showed me the routine. And Todd and I only got to see it, I think, two weeks before we shot it. It was everything we said we wanted to do: show women in power, and shoot these women with agency. But it was beyond our wildest dreams and certainly my wildest expectations.

I was interested in exploring the female body as a means to talk about our broken system.

Marie Claire: What goes into building and running a set where these actresses and dancers are nearly nude for a significant amount of time, and you want to make sure that they can set their own boundaries—that everyone is safe—but you still get the feeling you want on film, that the place is rowdy and a little out of control?

LS: It starts at the top. I knew it was going to be so important: having someone who was our comfort consultant and our stripper consultant, who was also there to ensure everybody was feeling safe and comfortable and had the space to do their work. It also was an incredible AD [assistant directors] department, honestly. They were sent from heaven, or we never would’ve been able to wrangle that many extras.

We had 300 background actors for Ramona’s dance scene, 250 patrons and 50 other dancers and employees at the club. So it was a lot to make sure that everybody felt safe and comfortable, while also making sure that the scene felt alive and electric and rowdy and rambunctious and masculine. Our producer, Elaine Goldsmith Thomas, gave a speech to them every night, to let them know they were a part of this and us. And no one broke that trust.

So I did a walk-through—an embarrassing walk-through—of Ramona’s routine, and pointed to people who were going to throw money and told them when they were going to throw money. We had an incredible choreographer who was able to show them the routine. Once Jennifer was there, we had as many cameras going at once to treat it like the stunt it was and the live event that it was, because it was Jennifer Lopez stripping in front of 300 people.

We just had to be really dialed in and vet all the guys and make sure that they were good people. And we also told our background actors, many of whom were real strippers, that they are in control. We told our background ladies that they could choose the guys [to go up to], not the other way around. So we started with that and ensured that everybody felt great… [rather than] just about letting the cameras roll on a working strip club.

Constance Wu and Jennifer Lopez in a scene from Hustlers.

Marie Claire: It’s so interesting to hear you talk about all the planning and rigor that went into those shots. [Elsewhere in Hollywood] there’s this pushback to what you’re describing: “Well, we have to be able to be wild and free on a film set/in the recording studio/in fashion, whatever, or we’ll never be able to create Art.” And yet it sounds like your experience was that having infrastructure in place—from hiring a comfort coordinator to blocking out when and where extras throw money—is what made it possible for the performers to be so free and do their work.

LS: Definitely. We certainly had a lot of women in leadership positions, which maybe [means we had] a certain group of men who are comfortable working for women like that, and naturally that just has a more balanced set. It was a group of women and men making this movie together. And I think men and women can and should work together, so as much as I loved working with women in leadership positions and hiring women in those roles, it was a really lovely balanced group of people who were all there to make a movie.

It’s always so important to make sure that your actors feels safe and comfortable no matter what kind of movie you’re making or environment you’re trying to capture. They need that space to do their work and hopefully lose themselves in it a little bit.

MC: In Jessica Pressler’s original story, the relationship between the women Destiny and Ramona are based on isn’t front and center, whereas in the film, it’s the crux of the story. When you read her piece, did you think that friendship was already there between the lines and just not out in neon? Or did you invent it for the story you were trying to tell?

LS: I thought that when I read between the lines of the story, there was a compelling friendship story there. I’ve heard from Rosie [the basis for Destiny’s character] that the dynamic was much more that of business partners and equals, which certainly isn’t the dynamic that exists in the movie between Destiny and Ramona. But I found that dynamic to be really compelling.

It became the focus because I think there’s something about the collective female experience, about the relationship that we have with each other, that’s very different than anything we have with our partners, our kids, our parents. It’s something very specific, when we can choose our own families. We do that with our girlfriends; we pick our own sisters, and sisters fight. And those friendships run deep and can hurt but also can save your life, and can also ruin your life, and have a profound effect on your life in ways that nothing [else] can.

Even though we all have very different experiences, there’s a collective experience that we all share of walking through the world being valued as women. And for everybody navigating that broken value system, in which women are valued for their beauty and bodies—for sex or motherhood—and men are valued for money and power, and the trickle down of both of those things seems to seep into everything in our culture.

I don’t fault anybody for working within that value system, or trying to find a way to thrive in it. I don’t fault any gender or job. But is it any wonder that something like the financial crisis happens when greed is rewarded? When we tell people that their value is the size of their bank account? I was excited to explore that in these scenes. And it felt like the friendship was the way into that. It was these women with different perspectives on the world, themselves, and their bodies, that they have a lot in common, and that we all do. That exercise in empathy that the writing is, that all writing is, for me anyway, it really came through this relationship between the two.

We're all navigating...that broken value system, in which women are valued for their beauty and bodies—for sex or motherhood—and men are valued for money and power.

MC: It’s very fun and revealing to see how men and women who accrue wealth in this movie spend it differently. With the men—part of why they’re easy marks—is the “thing” they want to buy is the company of women, and what comes with that (booze, mostly). Whereas it’s not like when Destiny gets money, she shows up with a cuter boyfriend. The women spend it on themselves, on their families, and each other.

LS: I think there’s joy in the celebration of women making money. I understand that they’re doing it the wrong way, going about it the wrong way, but I think there’s joy in this. Because we’re often seen spending and shopping, but we’re not often seen earning and providing. And I think that’s really important, to see that part of it as well.

I was asked the question, early on, by people who were afraid to make the movie, “Are the characters good enough moms?” And I thought, how strange! You’d never ask that of male characters. Certainly not of, say, Walter White. I just thought that was so interesting, and it gets back to that collective experience, that we all have completely different individual experiences, but there’s something unifying about that—all these people out of breath at the starting line with different numbers of hurdles behind them.

MC: Your point about watching these women earn and provide… There are tons of shopping spree scenes in movies, but it is rare to see women spending their own money. Usually it’s Pretty Woman–style: A dude gives a girl a credit card.

LS: Exactly! [Though], from a certain point of the movie on, they do just take a guy’s credit card….

But I agree, I think that’s part of the joy of the early shopping spree, Destiny is counting out her ones. She worked for every one of those bills. And a lot of the times, if you’re not accustomed to money and you have any experience with not having money—which I certainly have and these characters have—the joy of earning is so powerful. Deciding that you’re going to take however many lap dances add up to that bag and decide, I’m spending this on myself, I’m giving myself something, and I’m going to enjoy that I did this myself. That’s incredibly powerful and at a certain point, probably, addictive.

I think that’s why it’s easier to celebrate those earlier scenes: You really know that they earned it. That was part of what I wanted to show: sex work is work. Stripping is work. What these women do for a living, this is their jobs. They’re paying their bills and buying a bag every once in a while, but they’re working for a living.

That was a disconnect early on for people, talking about this project. I don’t think they saw what these women did for a living as work. It felt like there was such a large judgment around what they did. What you see them do is their job, and they’re paying their bills, going to school, they are moms and sisters and daughters and wives, just like you and me. So I felt that kinship to them immediately, as a person in my field who, I certainly have tried to get money from people! So for me it was incredibly relatable. I know these girls. I grew up with girls who stripped after high school and college, paying off student loans. I never found anything shameful about it. Even though it wasn’t my personal experience, I really related to what they were doing, and what it is to make ends meet when you don’t have money and you need it.

The allure is that there’s this potential for fast money. But it’s not easy money and there’s no guarantees and no job security at all, and new laws being put in place making it so hard for these women to earn a living and making their conditions less safe, like SESTA/FOSTA. It’s incredibly dangerous, and the strippers are not employees of the clubs, so they don’t receive those benefits.

I’m thinking of this value system of ours and wondering why we criminalize women for working within that system. For me, going forward, if there’s one hope for me outside of the movie, it’s that it can lead to constructive conversation about how to better the work conditions for these women, and how to give voice to them, and for them to be able to tell their own stories and live their own lives with the dignity that they deserve.

For more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.

Jessica is a writer based in Washington, D.C. You can read her in The Washington Post, Vulture, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, and a bunch of other places. She's also the culture editor of ThinkProgress.