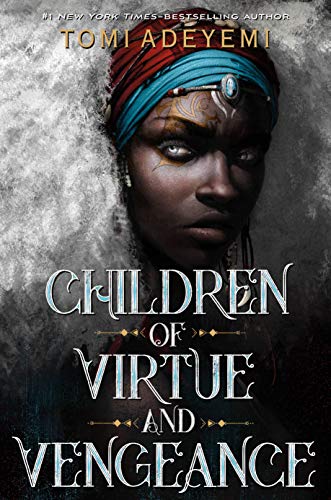

Tomi Adeyemi Makes Magic. Again.

With the highly anticipated release of Children of Virtue and Vengeance, the sequel to the bestselling, politically charged fantasy Children of Blood and Bone, the 26-year-old proves that she's just getting started.

Tomi Adeyemi talks fast. Her supersonic pace falls somewhere between the speed of a debater on a dwindling rebuttal clock and a meandering philosophy professor on the cusp of making a brilliant point. "I just decided today that I'm satisfied with Children of Blood and Bone," the 26-year old Nigerian-American author says of her debut novel, the critically acclaimed 2018 Y.A. fantasy that has spent 90 weeks on the New York Times Bestseller list. “I’m ambitious, I’m a Slytherin,” she continues, almost breathlessly. “I don’t want things to be really good, I want them to be really great.”

Breathless—and really great—are apt descriptors of Adeyemi's life for the past three years. At 23, she started writing Blood and Bone, the first in a projected trilogy, which scored a reported seven-figure book advance. Prior to the book’s publication, Adeyemi negotiated and netted a massive movie deal with Fox 2000, acquired by Disney’s Fox/LucasFilm. (Rumor has it that LucasFilm president Kathleen Kennedy chose Blood and Bone to be the first feature to be produced by the company outside of Star Wars and Indiana Jones.) Adeyemi’s publishing company Macmillan asked her to start writing the sequel before the first book was even released—they wanted it out on the heels of Blood and Bone’s rightfully anticipated success. Being a Slytherin, Adeyemi delivered: Children of Virtue and Vengeance comes out today, December 3, a mere 20 months after its predecessor hit shelves.

I’m speaking with Adeyemi over the phone, a few weeks before the release of Virtue and Vengeance. She's in her apartment in San Diego, throwing squeaky toys to her Bernese mountain dog between questions. Her electric energy radiates through the phone receiver, even though she says it’s the first time she's felt relaxed since turning in the final draft for Virtue and Vengeance in September.

“All of it happened so fast, and it never slowed down,” she says of the avalanche of the last few years. Now, she’s taking “time off,” she says, to “actually think about what it means to put something out into the world.”

I don’t say this to Adeyemi, but I have a feeling this tranquility won’t last long. Her sophomore novel is highly hyped; legions of fans have already pre-ordered the book. It’s listed on countless “must read” lists across the web. Good Morning America announced Virtue and Vengeance as its December book club pick. Fanfic has helped readers bide the time, but they’re anxious for the real thing.

Fan art for Blood and Bone: Top: Keith Thompson (Map or Orïsha). Bottom left: Jacqueline N. Daggers (heroine Zélie). Bottom Right: Mariateresa Mazetto (Zélie).

Blood and Bone masterfully combined real-world problems (class discrimination, systemic racism, violence) and epic fantasy. The series is set in Adeyemi’s fictional, mystical West African land of Orïsha (the name is derived from West African mythology), where some of the population held magical powers until a ruthless king targeted their kind. Heroine Zélie, a teenage divîner (a person who has the ability to do magic), takes on the brutal monarchy in an effort to bring magic back, while simultaneously navigating the complex feelings she has toward the king’s two children (one of whom is a love interest).

In Virtue and Vengeance, Zélie continues her quest, but the stakes are higher: She’s lost people she loves. She’s reeling from trauma. The fiery passion she wielded in Blood and Bone has aged into untamed rage—vengeance—which Adeyemi dexterously handles within the novel’s pages. Though marketed as Y.A., Adeyemi doesn’t flinch when it comes to describing the bloodbaths of war. Magic is still found throughout Virtue and Vengeance, but the sense of wide-eyed wonder present in Blood and Bone feels wistful this time around. It’s like the moment in Harry Potter—one of Adeyemi’s early inspirations—when readers realize it’s not all chocolate frogs and Wingardium Leviosas. There are Horcruxes, and they are coming for your protagonist.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Adeyemi has been writing since she was 6, but didn’t originally consider it as a career. “Writing was always playing quietly in the background,” she says. “I was always rewriting a story.” Her passion for the craft lead her to Harvard, where she studied English literature. But then her path then diverged: She completed an internship with Morgan Stanley, and, after graduating, took a job in data marketing at an entertainment company before pivoting full-time into writing. The leap felt inevitable, one of those nagging gut feelings, but it wasn’t without some anxiety. “I wanted someone to tell me that instead of writing from six to midnight every night, that I could write from nine to six,” she says. “I was looking for someone to give me permission. I just realized that I’m the one who gives myself permission to quit my job and try and make it happen.”

She took a crack at writing a book “about a girl who discovers the other layer behind life and death,” but it was rejected by 60 agents. Instead of revising, she started fresh with a story inspired by a trip she took to Brazil on a fellowship, where she happened upon figurines of Orisha, gods of Nigeria’s Yoruba people, in a souvenir shop. Her parents were from Nigeria—they immigrated to American in the early 1990s before she was born, fleeing the civil war—and Adeyemi felt immediately connected with the pieces of art. Inspired, she began researching their mystical mythology, knowing it could be the basis of a compelling fantasy book. She finished her first draft in 30 days.

If that original, unnamed manuscript was, as she calls it, her “MFA in publishing,” consider Blood and Bone her dissertation: “For that first book, I was working from a place of desperation. I wanted any agent and any deal,” she says. With Blood and Bone, desperation turned into intention. “Once I gave myself permission, I realized I didn’t want a bunch of people to say ‘yes.’ I wanted the right yes.”

She got it. Macmillan offered her a seven-figure book advance, one of the largest ever for a debut writer in her genre. Her brief experience in the corporate world helped arm her during the negotiation phase of her book and, later, when optioning the movie rights. “Being in environments that were purely capitalist gave me a lot more perspective going into publishing,” she says. “If you’re not thinking of yourself as a business, you’re always going to be a worker. True gains come from being a businessperson. They come from creating your own institutions, empires, stories, and franchises.”

She approached the discussions the way her characters—people who can communicate with the dead and ride giant lions into battle—would. “I’m a shark, I’m an aggressive person,” she says. “When people tell you, ‘I’m trying to make your dream come true,’ they’re trying to make money off of you. You have to be very in-tune with what it is you truly want in order to get you there.”

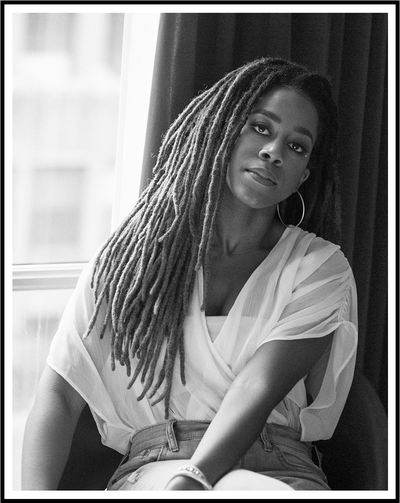

Tomi Adeyemi.

She calls her ambition both a gift and a curse, but she refuses to apologize for it. Speaking to the compromises she had to navigate when selling the book, she says: “As women, we’re also hardwired to be easy and to make things easy. I no longer care about easy, I care about right.”

When Blood and Bone came out in 2018, it sparked conversation. The book captured the cultural ethos, the unrest and turbulence erupting across the nation, while still celebrating the lengths of imagination. It was a book that readers could slip into to both forget and be reminded of the world around them. Inspiring and destructive. Like Zélie, who faces discrimination and classism in both books, Adeyemi has witnessed the effects of systematic injustice firsthand. And, like Zélie, she still rises.

“The reason I’m here is because I’m a young black woman,” Adeyemi says, when asked if she felt resistance, professionally, as a young woman of color. “I’ve been a young black woman my whole life, so this is the grandest battle I’ve had to face and fight. But I’ve always had to fight battles. When you go through a personal war, you leave it a warrior.”

Blood and Bone was hailed as a parable for the black experience in America, but Virtue and Vengeance is new territory. Among its more adult themes, Virtue and Vengeance is, at it's core, about a country torn apart by civil war. For the book, Adeyemi read up on the Vietnam War; she spoke with people who’ve served to gain insight on the brutalities they see. The world she has created isn’t all fantasy. “As a Westernized audience, a lot of this stuff is fiction for us,” she says. “But I’m very aware that this isn’t fiction for a lot of people, especially a lot of children, in the world.”

Though her work is “dark as hell,” it is often sanitized in comparison to the inhumanities she’s learned about in the real world. The concepts she broaches, however, are never dumbed down, one of the grievances she has of other books within the Y.A. category. She knows her readers are smart. They crave literature that they can see themselves reflected in. It’s one of the reasons they can’t put Adeyemi’s work down.

I ask Adeyemi if she has started to work on the third, final unnamed book of the series— given her track record, I’d imagined she has squirreled away some 600 pages of epic conclusion. She pauses, maybe for the first since we started speaking. “No, and I love it,” she says. “I smile every time someone asks me. For the past three years, I was always writing, I was always trying. Now I’m trying to live in that place where I'm not like Peter Pan trying to catch up to his shadow.”

For the moment, Adeyemi has put ambition on pause in favor of 20-something fun. There are moments during our conversation—though fleeting—that I’m reminded of Adeyemi’s age. In the past year, she went to her first rave (she said it was awesome). She started to bullet journal, something she’d wanted to do for years. She binged “every dating show,” with the exception of Love Island, which doesn’t move fast enough for her. “That part when you’re watching these dating shows and you recognize something in yourself is so illuminating for me,” she says. “I think that also brings my intensity. It’s a complicated love of psychology.” Like I said—fleeting.

For more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.

RELATED STORY

Megan DiTrolio is the editor of features and special projects at Marie Claire, where she oversees all career coverage and writes and edits stories on women’s issues, politics, cultural trends, and more. In addition to editing feature stories, she programs Marie Claire’s annual Power Trip conference and Marie Claire’s Getting Down To Business Instagram Live franchise.