2000s Nostalgia Is As Prevalent As Ever. But These Authors Aren't Sure Our Cultural Obsession Is for the Best

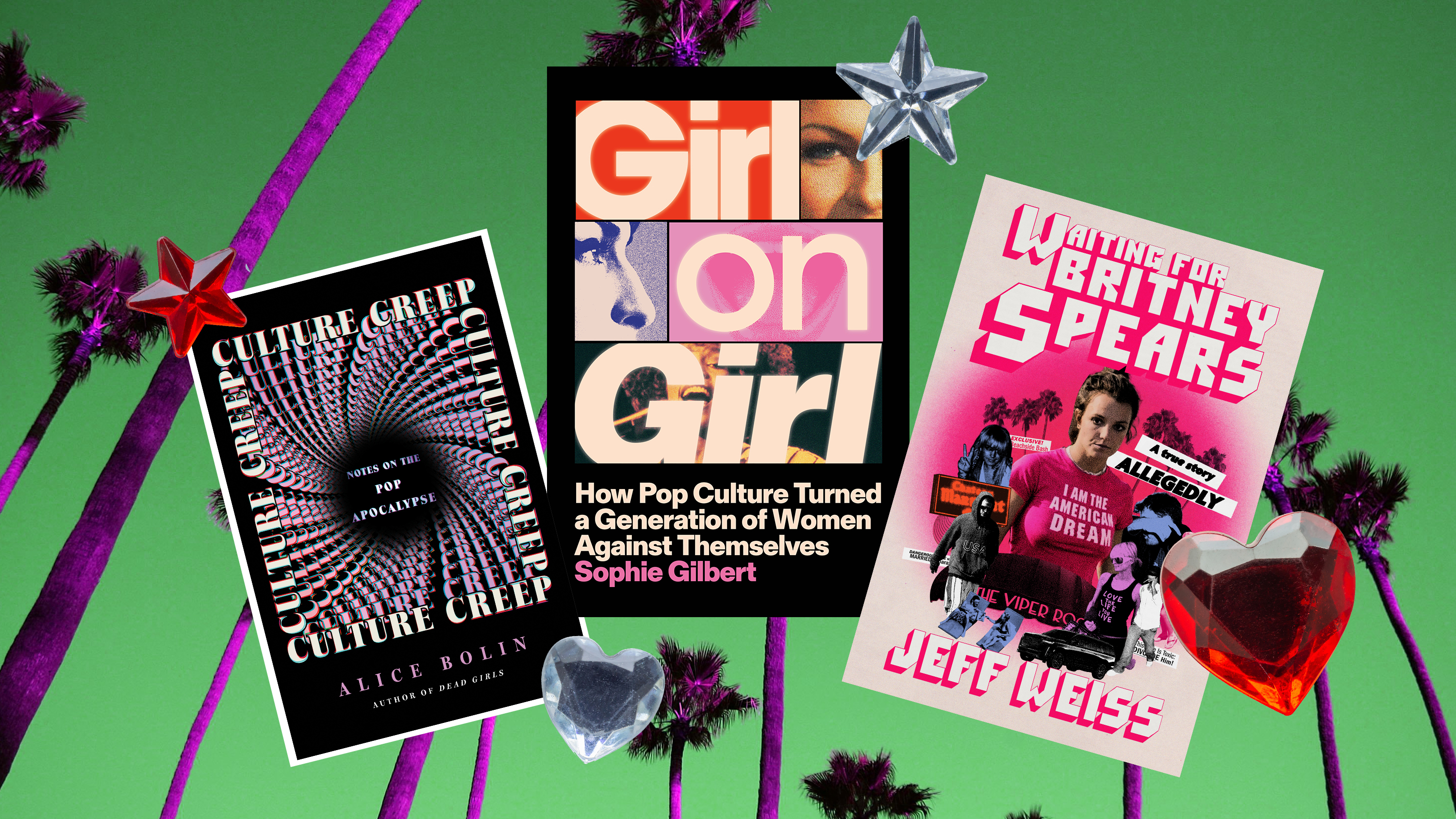

The 'Culture Creep,' 'Girl on Girl,' and 'Waiting for Britney Spears' writers discuss their new books and why we can't let Y2K go.

In November 2006, paparazzi captured an image that has since defined the decade: a shot of the tabloid holy trinity—Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, and Britney Spears—getting into a car after a night out at the Beverly Hills Hotel. At the time, the trio were the most hotly covered celebrities by print tabloids and emerging gossip blogs; Spears was in the midst of a divorce after the birth of her second child, Hilton had recently released her debut album and been charged with a DUI, and Lohan was covered more for her partying than her considerable talents.

In the 19 years since the New York Post published that photo, misogynistically dubbed “the Bimbo Summit," it has spawned artwork, a musical, and even Hilton celebrating its anniversary on Instagram. Its lasting legacy alone shows the cultural impact Y2K has had on today, from the proliferation of celebrity obsession to the 24/7 news cycle.

Despite the 2000s feeling not all that long ago, nostalgia has hit everything, including fashion, TV reboots, and a new generation of pop stars. Inevitably, it’s made its way to the literary world. But rather than regurgitating the past, new books are interrogating the period and ephemera we know and love—moments like that shot of the Hilton, Lohan, and Spears.

Lindsay Lohan, Britney Spears and Paris Hilton photographed together on November 26, 2006 in L.A.

Three of this summer’s must-reads explore the lasting effects of Y2K: Sophie Gilbert’s Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves, Alice Bolin’s Culture Creep: Notes on the Pop Apocalypse, and Jeff Weiss’s Waiting on Britney Spears. Girl on Gil, released in April, looks at the era’s hyper objectification and sexualization of women and how many of the dominant themes of that time, like porn, have influenced cultural consciousness today. Meanwhile, Bolin’s essay collection, published on June 3, shows the throughline between aughties popular culture and what’s trending now, from diet-tracking apps to Animal Crossing. And Weiss’s book, released this week, is an autofiction take on his time writing for tabloids, examining how that paparazzi period changed modern media.

With all three books on shelves now, Bolin, Gilbert, and Weiss spoke to Marie Claire about their initial inspirations for writing about the 2000s and the decade’s impact on social media, politics, and everything in between.

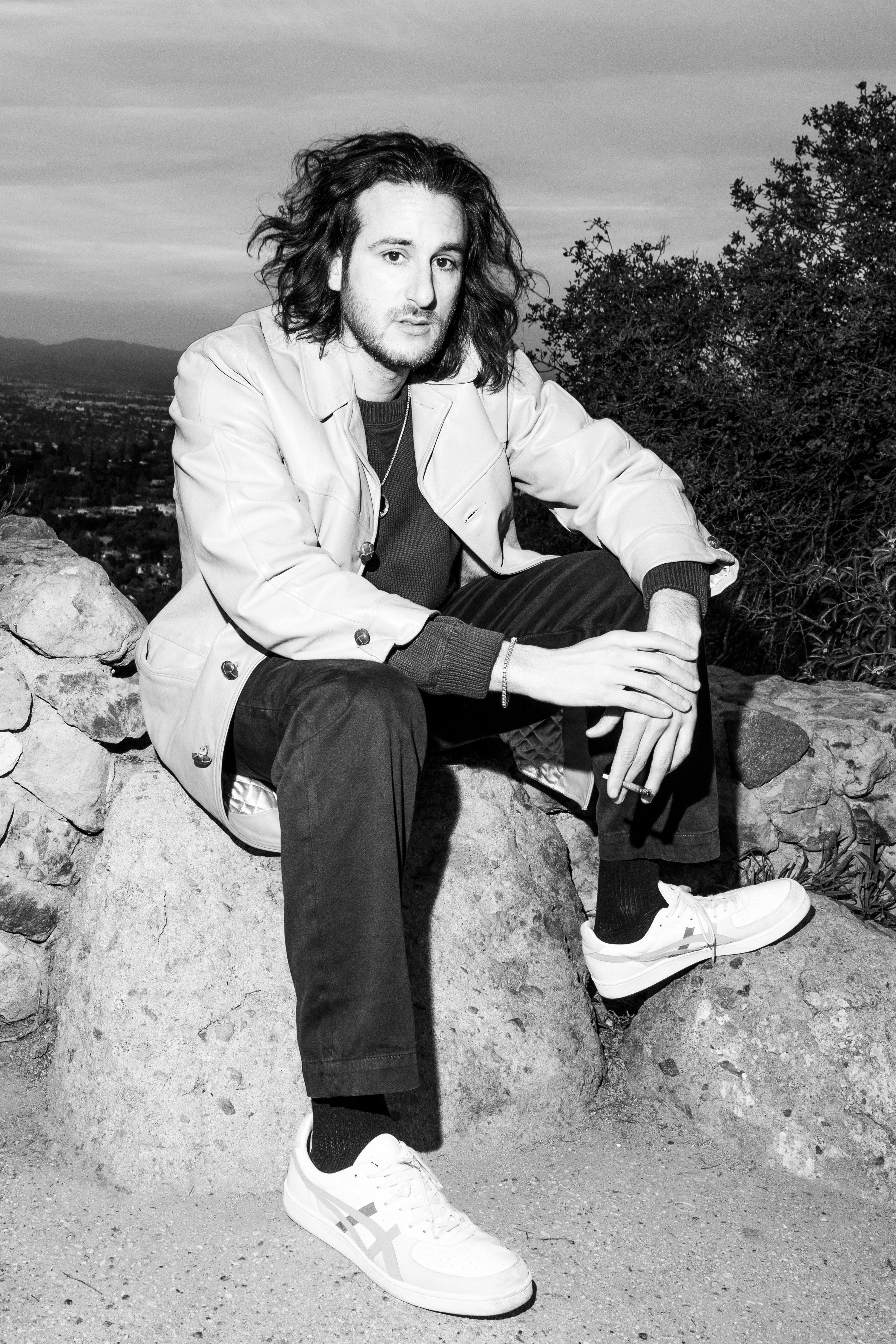

Culture Creep: Notes on the Pop Apocalypse author Alice Bolin.

Marie Claire: What was the initial inspiration for writing about this era of pop culture?

Alice Bolin, author of Culture Creep: My initial idea for the book had a lot more to do with [my obsession with magazines]. As time has worn on with the pandemic, Trump, all of this stuff feels heavier. Just being in your 30s, the nostalgia does not feel as light and fun to me anymore. There's a bigger theme about how we're living in this future that feels so much like the past, how much of our culture now is this nostalgia machine, and how much that reflects stagnation and economic stagnation. It became a lot more about interrogating this culture that hinges on nostalgia in so many ways.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sophie Gilbert, author of Girl on Girl: I found myself around 2021 circling the 2000s because it felt like a lot of culture was pointing to that. When Promising Young Woman came out, it had a specific way of nodding back to that period and what it was doing to us. The combination of honoring the real zing and sparkle of things like “Stars Are Blind,” but also interrogating the gender dynamics and the rape culture of the era was really interesting. [It was a] formative period for me because I turned 17 in 2000, and then my entire 20s were in that period. It made me wonder what it had done to millennial women.

Then Roe v. Wade was overturned, and we had this period of Trump and #MeToo, and it felt like progress for women was not inevitable anymore. I wondered what the culture might be able to say about why I felt so disempowered and why women in general seemed less powerful than they'd had in a long time.

Waiting for Britney Spears: a True Story, Allegedly author Jeff Weiss.

Jeff Weiss, author of Waiting on Britney Spears: My first book is a book about Britney Spears, which is such a reflection of my life that I was so haunted by pop culture because that was the culture that I knew. I wanted the timeline to closely mirror my experiences in this world. Of course, there were certain things where you had to finesse it to make it make sense. Because at the end of the day, you're going for more of a deeper underlying truth that we subconsciously understand more than the actual, because the truth is sort of impossible to know. I was very adamant about having Britney's facts be as accurate as I could. But even so, that's impossible, right? So you're forced as a writer and a journalist to sift through all this ephemera, and that is the historical record. And then there's Britney's truth, which is its own reality unto itself. Then there's the truth as told by the tabloids, and then there's the truth told by her family. And there's the truth as told by all these people around her. What's so interesting to me was I found it in a crazy way. This is the first rendering of this era that wasn't written in real time.

MC: How do you see Y2K culture impacting today’s pop culture?

AB: One of the things I've been thinking about a lot is how nostalgia affects a break from the past. These things were not that long ago, and there's a huge amount of continuity between culture then and culture now. Things have just snowballed in crazy ways. The Kardashians, that's when it started, or Paris Hilton's connection with Donald Trump—there are all these things that are still interwoven, but nostalgia makes us feel like that thing is over. There's a lot of damage that's done in not recognizing the ways this culture is continuous, and actually that things have not changed. It is a sign of stagnation of how this culture is not working, and culture at large in society is not working for anyone except these people who were benefiting back then, too.

Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves author Sophie Gilbert.

SG: I think the process of reconsideration began with Monica Lewinsky's 2014 essay in Vanity Fair, which seemed to ignite something. After that, you had the process of looking at the ‘90s and the different women who were unfairly maligned and dragged through the ringer in that era. And the 2000s is having its turn. We're thinking about it differently, not just because there's this moment of nostalgia for it in culture, but because the people who are most imprinted on it are now coming of age in ways that are making us able to reckon with it a bit more.

The huge influence of porn was something that came through in my book, in which suddenly porn had gone from something that you had to watch in movie theaters to something that you had to rent in a video store to something that you could watch in a blink online, bled into culture. I think we all, living through this period, absorbed the idea that being good at sex meant performing sex rather than enjoying it…[and] the idea that for women, power was sexual power, and it was the only kind that mattered.

Also, this shift in celebrity around the turn of the millennium—the way that suddenly all you had to do to be famous was to be visible. That really changed the future for a lot of us and set us up for the age of Instagram, influencers, and TikTok.

JW: My working theory is that the tabloid sensibility has completely become the mainstream sensibility of modern life. It was the thing that eroded the guardrails, right? You watch the Matt Lauer interview with Britney, and it's haunting, especially in light that Matt Lauer turned out to be doing heinous things. He was using the tabloids to launder these salacious allegations so he could put them on the news, so he could be like, Well, NBC News isn't reporting them, but these tabloids are. You are basically giving it the validity of a national news organization that's respected. It's the Truman Capote quote that I included in [the book] that said, “All literature is gossip,” but now all culture is gossip. That is our culture. We have a carnival tabloid president. If you are really tracing it, you're like, Of course, now we live in the Andy Warhol world that he predicted. And then it becomes round two. It's actually Paris Hilton's world, and now we are in Paris Hilton's world. Everyone is trying to be Paris Hilton.

There's a lot of damage that's done in not recognizing the ways this culture is continuous, and actually that things have not changed. It is a sign of stagnation of how this culture is not working.

Alice Bolin

MC: Do you think the beginnings of reality TV led to us mirroring that and becoming our own brands online today?

AB: In the late ‘90s into the 2000s, the paparazzi became extremely powerful and prevalent. There were gossip blogs, and there were even nightclubs that opened in order to cater to the paparazzi. You can see how much this gossip industry completely was symbiotic with brick and mortar businesses. Things are even more invasive now because of social media. Everybody's the paparazzi now. Everyone's monitoring these people, and it's creepy.

In addition, it's like Paris Hilton in her memoir saying, ‘I sell my own image or I control my body.’ But you're still being forced to sell your image so that someone else doesn't do it. The Kardashians have made billions off of their own bodies, their own images, which [one could] say [is] preferable to Hugh Hefner making that money or TMZ making that money. It's all a symbiotic ecosystem. Those other gossip industries are still feeding off these social media companies and accounts. And clearly our taste for it has only grown.

SG: In the 20th century, if you wanted to be famous, you had to be famous for something. You had to have a skill or a talent or a moment of notoriety. Then suddenly, with the internet and the rise of the gossip industry, both online and the industrial gossip magazine phase in the 2000s, they had all this space to fill, and reality television was happening at the same time. That created this new paradigm where all you had to do to become famous was to let yourself be very visible in front of the cameras, to open up your life to cameras, to make yourself exposed and, in some ways, overexposed. Or, you could wear a funny dress and stand at the right events, pose for photographers, and talk to them. That was a valid way of getting famous in the early 2000s, and it, in some ways, made celebrities seem more accessible to the rest of us. I think it trained us all to think of ourselves as potential objects in a way that, for me, certainly has been very hard to unroot from my own mind.

JW: I have this theory that it all spawned at the Coachella VIP, and it's the anthropological evolutionary tale of humanity. Coachella becomes a thing in this era where you go from being a human to an influencer to a brand, and then you become an artist. Paris Hilton was that, right? She was a human being who became a brand that became a TV show that became a pop star.

MC: How did Y2K culture impact women? Does it dovetail with #MeToo?

AB: It's a huge theme in the book because, in some ways, #MeToo was very consequential and really did change how we see sexual politics, sexual harassment, sexual violence. What I say is that it didn't go far enough when it had the chance to. That's often the case with these radical political movements, of course, but especially relying so much on the justice system to be what takes down these people. It was a huge mistake because Trump can pardon whoever he wants. People get out of jail, and they just go on with their lives. Especially at the same time that we're having this reckoning about racist policing and the prison system, there's a huge amount of irony that separates people, where you start to think #MeToo is at odds with Black Lives Matter, when they should be part of the same thrust toward justice.

I still think we haven't seen the full weight of what #MeToo did. This focus on celebrity culture was a huge downfall of this movement. Of course, we want these famous people to be brought to account, and the entertainment industry is this unregulated wild west, so that did need to be addressed. But it was very difficult then to attach that same amount of energy to harassment in people's own lives, violence in people's own lives. It's a lot more about changing culture rather than addressing it through judicial means.

SG: There was so much disgust that was leveled at women during [the Y2K] era, and especially at their bodies that we all internalized. The idea that we might be found disgusting by someone in a sexual context, knowing that we couldn't rely on privacy, even in a sexual context—images might be shared, video might be shared. What that does is alienate you from your own sense of self. This period was about making women obsess over their so-called flaws and thinking about what they needed to change about themselves. So much of that is a distraction from thinking about what we want, what we need. The idea that when we're hating ourselves and we are projecting that hate onto other women, in turn, we're not focused on the core things that we need.

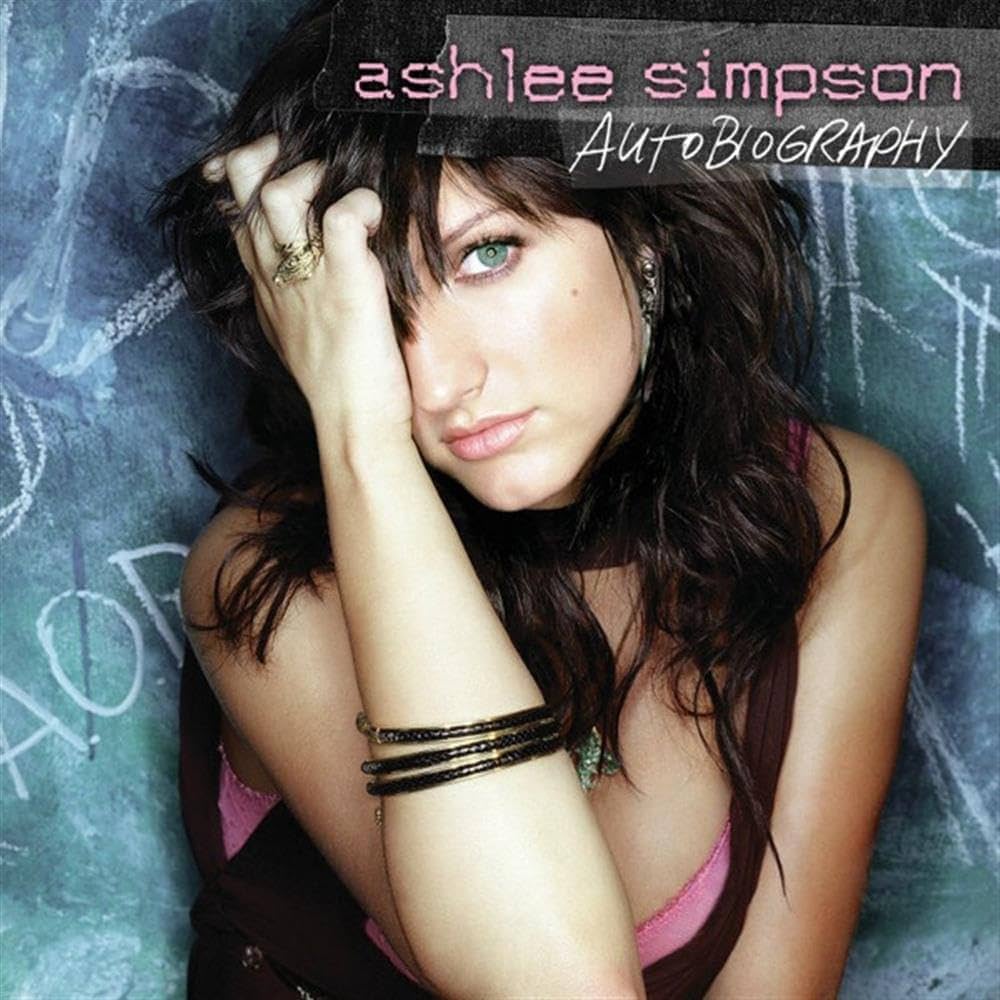

The cover art of Ashlee Simpson's 2004 album Autobiography.

MC: What are your favorite and least favorite things from the era?

AB: Autobiography by Ashlee Simpson. I'm a huge Ashlee apologist, especially that album. I still listen to it. My least favorite is that brand of evangelical Christianity. That's everywhere now—purity rings and that culture.

SG: The O.C. because I loved that show.

That brand of male photography that puts young girls next to penises, I would eliminate that from the island. I will implicate Terry Richardson, but also American Apparel.

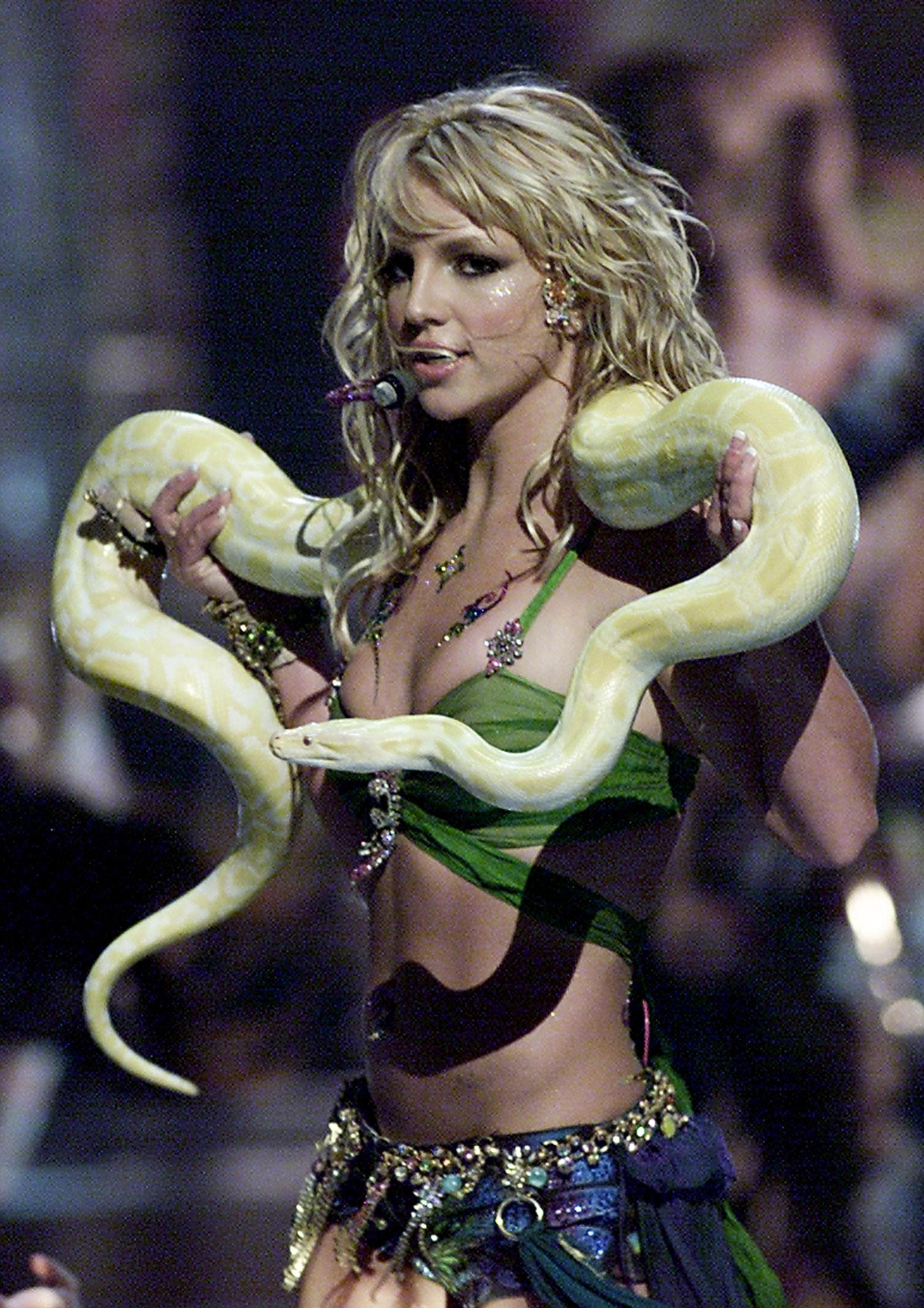

Britney Spears performing at the 2001 Video Music Awards.

JW: Britney dancing with the snake at the VMAs. In my head, it's a Jewish holiday at my uncle or my cousin's place in Palo Verdes. I remember watching and being like, I’m in love with her. Like, What kind of mystic ceremony did I witness? I feel like it's that fertility ritual from ancient Babylon.

I hated Justin Timberlake. I fucking hated “SexyBack.” I thought it was a dumb lyric. He was dressed like a mortgage broker going to the club.

MC: Why do you think younger generations have such a thirst for discovering Y2K pop culture?

AB: The pendulum swings back, and kids who didn't experience it or who were young start to reimagine these times, and they see it through a different lens than the people who lived through it. They don't necessarily see the bad parts. It becomes this fantasia of this fun, bright, poppy, teen aesthetic. It's certainly something to have fun with and play with and remix. There's something where our times reflect that time: war and militarism, the Nepo baby thing, old money. There are threads in culture that harken back to that time in addition to it being a fun aesthetic to play with.

SG: There's so much about it that's enticing, and it feels like what's being reclaimed is the surface-level aesthetic dazzle of it, and not the power dynamics, which, thank God.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Kerensa Cadenas is a freelance journalist based in New York. She's previously held positions at Thrillist, The Cut, Entertainment Weekly, and Complex. Her byline can be found at publications like Vanity Fair, Indiewire, Rolling Stone, Vogue, NYLON Bustle, Vulture, and other outlets. She's always had a pop culture obsession from film, literature, television, music, and everything in between. On weekends you can find her going dancing, seeing comedy shows or films, or hanging out with her cat.