The Stories Malala Yousafzai Was Most Nervous to Share in Her New Memoir

In a candid conversation ahead of the release of her new book, the activist reflects on life beyond advocacy—from her years at Oxford to falling in love and learning to live on her own terms.

The week before her new memoir hits shelves, Malala Yousafzai greeted me in her Manhattan hotel lobby with the easy calm of someone who’s lived a dozen lives before 28. Around us, the space buzzed with business travelers and rolling suitcases, but she was easy company—warm, thoughtful, quick to laugh.

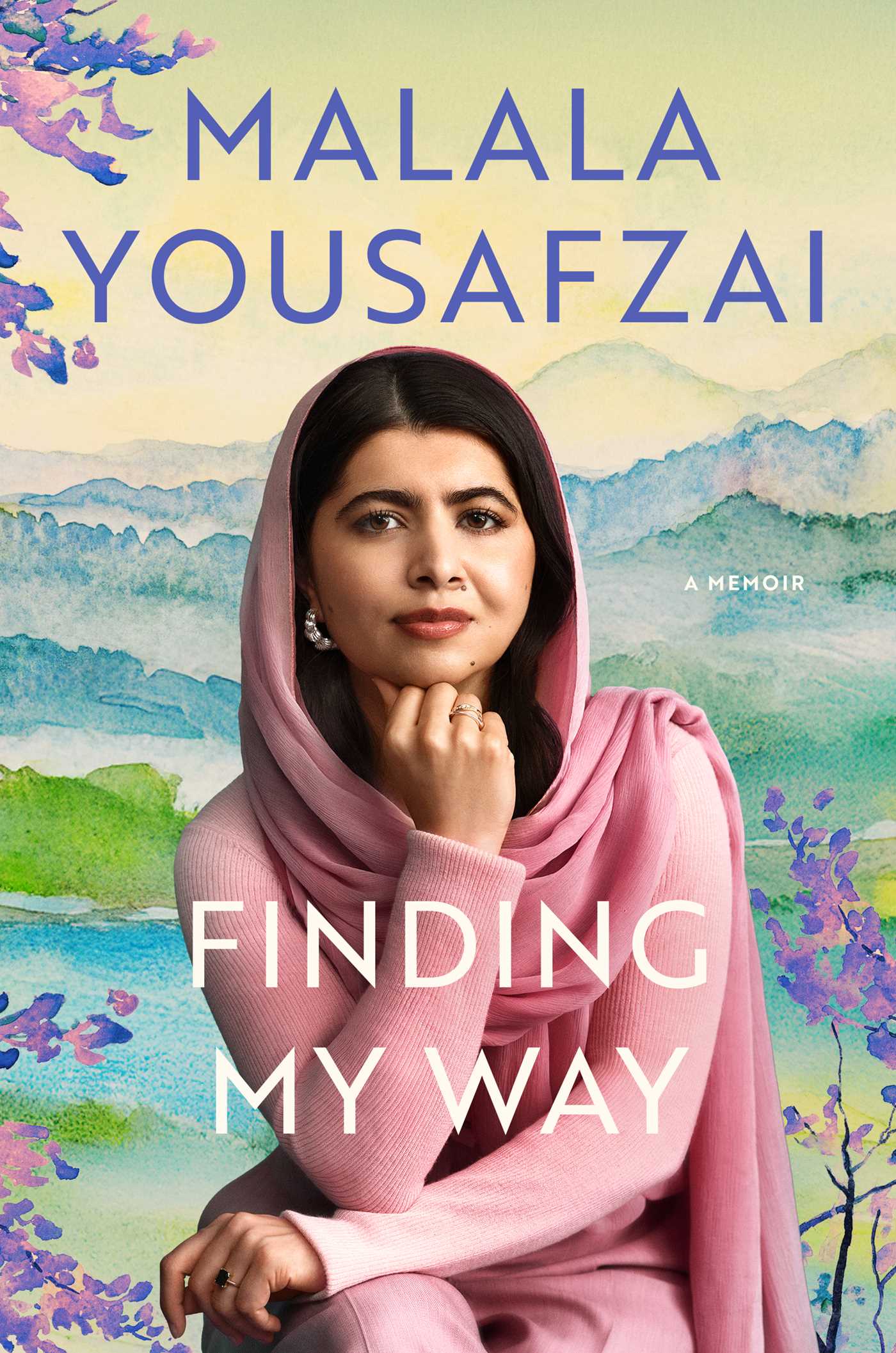

In her new book, Finding My Way, Yousafzai sheds the halo that’s long surrounded her name. She writes about Oxford nights and essay crises, friendship and therapy, panic attacks and romance. Part coming-of-age memoir, part reclamation, it’s a portrait of a woman who has learned that courage isn’t just about defying extremists, but also about allowing yourself to be ordinary.

We discussed these topics, and more, at length when we sat down to talk earlier this week. This is our conversation.

To start us off, a big-picture question: When readers finish the book, what do you hope they understand about you—beyond the “tidy, tragic version” of your story the world often repeats?

I hope that when people read this book, they will know me more. I was still in a coma when people first read headlines about me, defined as a brave and courageous girl after I was attacked by the Taliban at 15. I felt that I had to sort of internalize that “saintly” image.

And there’s this wrong understanding—that when you become an activist, you're not supposed to have friends or a normal life. But in the years since, I have grown and learned so much in my time at school and college, and I’m sharing a bit of that. I’m sharing more of myself with people—talking about my love life, friendship, activism, mental health. So this is a reintroduction of me, and I hope that people will enjoy reading my story.

I don’t want to stick to the way people introduce me—with a past story.

Malala Yousafzai during an interview in London, July 12, 2024. The Nobel Peace Prize laureate spoke with AFP about Pakistan’s policy toward undocumented Afghans.

You write about wanting to blend in at Oxford—clothes, clubs, choosing not to lead every conversation. What felt like the first undeniably normal choice you made for yourself there?

The college principal sent me an email before I joined, saying he wanted to announce to all the students that I would be coming and that people should respect my privacy. I saw the email, and I freaked out. I responded, “Please do not do that.” Because the same thing had happened when I joined a new school in the U.K. I was so new to the culture and the country, and I felt that the students were introduced to me as this person in the public eye. So a lot of the kids were just confused and nervous about how they were supposed to treat me.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

At college, I just wanted to be introduced as any other student. And that’s what happened. I’m so glad he didn’t send out the email. And to be honest, people wanted to see me as a normal student—why would they want to be reminded of who I was outside of college? I’m here to learn and grow and find out more about myself. I don’t want to stick to the way people introduce me—with a past story.

You write that the sisterhood you felt with your new friends at uni felt “like going to a foreign country but knowing the language.” What did Cora, Hen, Yasmin, and Anisa each teach you that no classroom at Oxford could?

In my case, I’d had so little exposure to be with people my age. So at college, I wanted friends more than anything. They created a space of comfort for me where I could be myself. Usually, I had to think twice before I said anything. I thought everything I said was like a press statement or a quote. But with friends, you can be yourself. You can make mistakes, you can say the wrong thing, and they can help you correct it or understand another perspective. You can be silly. You can talk about serious issues, your past, your present concerns, thoughts, boys, astrology, crushes, essay crises.

I also wanted to be this rebellious student who was doing more than what I had imagined I would; so getting into trouble, breaking some rules, climbing the rooftop, or getting back into college at 3:00 a.m. And I remember every week, when I would get closer to my essay deadline, I would just freak out because I would have so much work left. But when I would look back and think about how I had spent my week with friends who had given me memorable experiences, I would not take that back for a second.

You really wrestle with the idea of marriage in the book—both as a feminist and as a young woman who’s in love. And then you decide to marry Asser. What ultimately changed your mind?

It was a cringe topic for me. I thought it was boring. I had also seen girls who were married off when they were children, or they were forced into marriages. They lost their future. And it’s not just a problem limited to one part of the world. Women have to make more compromises in many communities. So I was like, why would I want to lose something by deciding to marry a person?

And for me, I had worked so hard for my right to have a future—to be able to complete my education and advocate for other girls. I felt that I was doing a disservice to my cause if I decided to marry. You feel like you have failed or turned out to be the enemy. So I said, I’m not ready to take on too many fights in the world. I’m going to focus on girls’ education and on me. Even that is a big mission—to make it a reality in our lifetime.

If I hadn’t fallen in love, I would have not considered marriage at all. But in the end, I decided to marry because I understood that it’s about mutual agreement between two people who want to spend the rest of their lives together. That’s the most important thing. I looked at Asser and I reflected on who he was as a person. I spent some time with him, and I saw through his actions that he is a kind, compassionate, respectful person. He’s loving and caring…and he’s good looking.

Sometimes people don’t expect me to be romantic. But I am a very romantic person.

Malala Yousafzai and husband Asser Malik attend the 95th Annual Academy Awards at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood, March 12, 2023.

Which passage were you most nervous to include?

I was nervous about different people for different chapters in the book. I was worried how my mom would react to the parts where I have shared her story for the first time. But I know my mom stands by her opinions, and she would understand where I was coming from. My message in the book is that I am becoming friends with my mom, and I understand where her resilience and strength come from. But I also understand why she’s more protective and more concerned at times—because she has seen a lot worse happen to women and girls in her lifetime, and she just wants to protect her daughter.

I was a bit worried about including dating Asser, because I knew that would be taken out of context. I was a bit worried if my parents would be surprised by some of those “dinners”—now we would call it a date. Sometimes people don’t expect me to be romantic. But I am a very romantic person.

There’s also the other side of your life—the global stage, where you’re still fighting for girls’ education. After the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan, you describe calling world leaders. Most never responded, but many of the women did. Why do you think that was?

When I reflect on it, I think the women leaders knew what oppression by an extremist, patriarchal group would look like for women. I think women could relate to it more. They understood what it means for women and girls to not have the right to education, the right to work. I think the men leaders just did not understand the significance of it. They could not relate to the problem as much—probably. I still think about it. I still think about it and try to find what could explain why the leaders, especially men leaders, did not do enough.

And even now, it’s been four and a half years, they’re still not doing enough. The Taliban—who are the perpetrators—have been given a second chance and are repeatedly given more chances, while Afghan women are told to wait and to make compromises on their future. My hope is that things change for Afghan women. They have suffered so much. Afghan girls have not seen their classrooms for four and a half years. We cannot live in a world where girls are banned from education and it is a crime for a girl to be learning.

We have to be a collective voice to protect a girl’s right to education and to have our own future.

Malala Yousafzai attends the Girls’ Education in Muslim Communities Summit in Islamabad, January 11, 2025. The Nobel Peace Prize laureate said she was “overwhelmed” to return to her native Pakistan for the event.

What’s one boundary or habit you want young women to borrow from this book?

When I think about my younger self, I look up to her for her courage and bravery. But at the same time, I feel sorry for her because she thought that she was emotionally so strong—but that wasn’t the case. And now, when I look at my life, I have experienced immense love, immense joy, but also breakdowns, and pain and grief and sadness as well. And no matter how difficult it was, I am truly grateful for growing into womanhood

When I went through my own mental health challenges—PTSD, panic attacks, anxiety—I thought I had failed, that I couldn’t live up to the idea of being brave. But getting therapy and normalizing it taught me. So to young people who are doubting themselves, who are worried about their strength, resilience, or self-esteem—I know that these emotions feel hard and difficult to process, but they are part of your growth. Sometimes the journey can be hard and difficult, but all of these experiences can help us grow into a more beautiful, truer version of ourselves.

That’s why it meant so much to see the girls at my school in Shangla [the school she founded in her hometown in Pakistan] have their own counselor’s office—a place to talk, cry, laugh, dance, and let their emotions out. It reminded me how powerful it is when young girls are taught early that their feelings matter, and that taking care of your mind is part of strength too.

After revisiting so many personal and political chapters of your life, Is there anything that didn’t make it onto the page that you still want people to hear from you directly?

I’ve been reflecting on my activism, which I have done for more than a decade and a half now. And to me, the most powerful way is working together. That’s why the way I do my work now is by becoming an ally and supporter of other women activists around the world.

I’m supporting Afghan women activists, and I think about what’s happening in the world and how it affects girls’ education directly. So whether it’s the situation of girls’ schools being bombed in Gaza, or girls being banned in Afghanistan, or girls facing challenges in Nigeria or Pakistan—we have to be there with them. We have to support the local education activists who are doing the real work on the ground. And we have to be a collective voice to protect a girl’s right to education and to have our own future.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Malala Yousafzai’s new memoir, Finding My Way, is out October 21.

Noor Ibrahim is the deputy editor at Marie Claire, where she commissions, edits, and writes features across politics, career, and money in all their modern forms. She’s always on the hunt for bold, unexpected stories about the power structures that shape women’s lives—and the audacious ways they push back. Previously, Noor was the managing editor at The Daily Beast, where she helped steer the newsroom’s signature mix of scoops, features, and breaking news. Her reporting has appeared in The Guardian, TIME, and Foreign Policy, among other outlets. She holds a master’s degree from Columbia Journalism School.