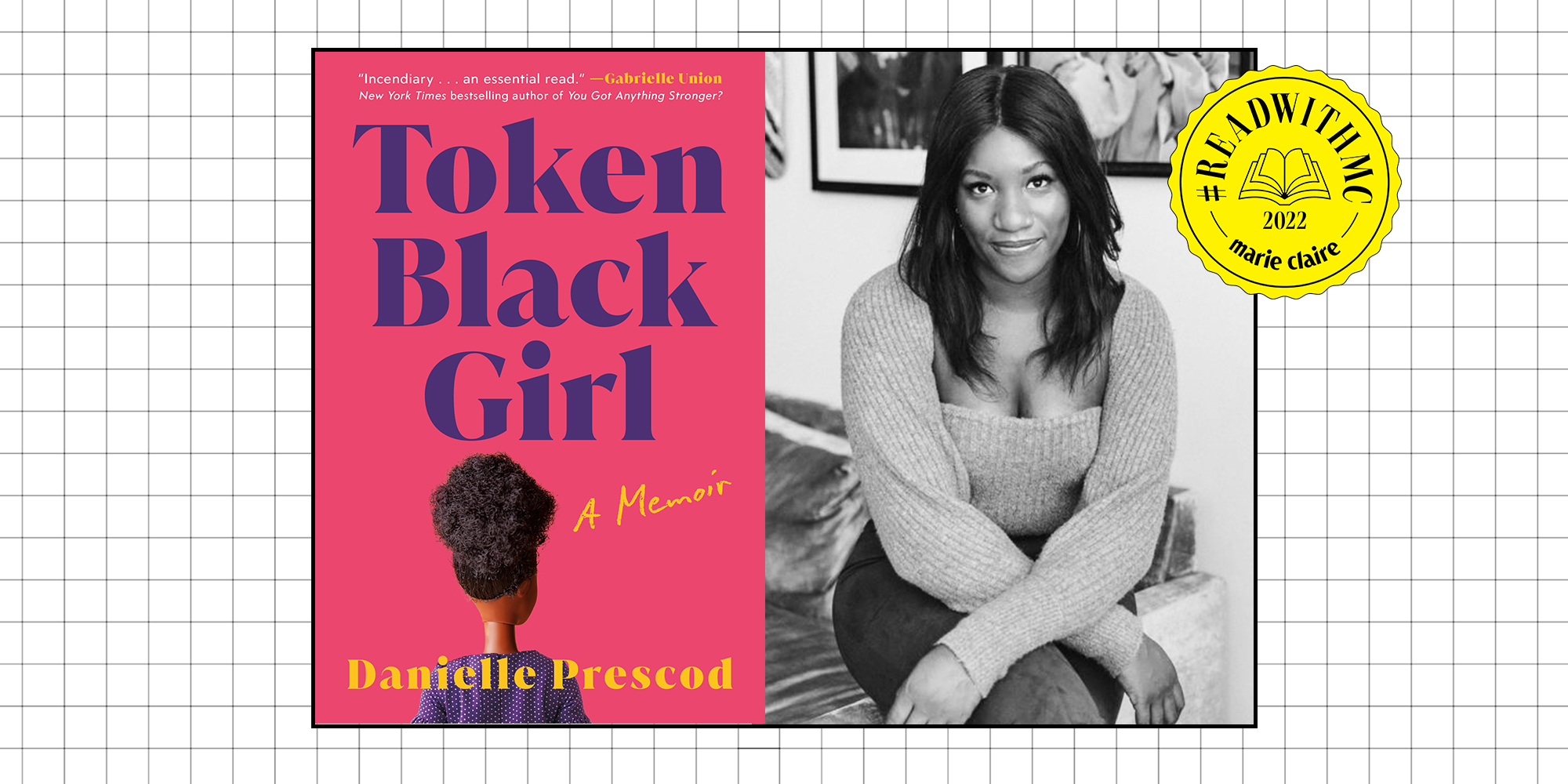

'Token Black Girl' Is Our October Book Club Pick

Read an excerpt from Danielle Prescod's new memoir, here, then dive in with us throughout the month.

Welcome to #ReadWithMC—Marie Claire's virtual book club. It's nice to have you! In October, we're reading Danielle Prescod's Token Black Girl, a refreshingly honest memoir on a beauty and fashion editor's experience in a predominately white industry. Read an excerpt from the book below, then find out how to participate. (You really don't have to leave your couch!)

In the summer of 2003, I turned fifteen years old. In July, the very same month of my birthday, Vanity Fair released a cover that is infamous within my generation of media obsessives. The cover teased a teen-focused special featuring five of the wealthiest and most popular female representatives of television and movie stardom. Amanda Bynes, Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen, Mandy Moore, and Hilary Duff posed draped around one another in varying shades of pastel pink. An expansion of the cover, hidden behind a fold, featured blue eyed brunette Alexis Bledel, broody Evan Rachel Wood, Token Black Girl Raven-Symoné, and token bad girl Lindsay Lohan. The cover line read “It’s Totally Raining Teens!,” a cheeky nod to youth-speak and Vanity Fair’s way of cementing an authoritarian cultural claim on who the “teens” of the times were. Cover expansions are significantly less popular in the modern media landscape, maybe because it’s cruel, but perhaps more practically because people are now likelier to see cover images on a screen than in the aisle of their local CVS. At the time, it was a subtle and not-so-subtle way to both include and exclude people, with the message: “We need you, but you’re not quite cover material.”

Teen Vogue, Vogue’s kid sister, would be launched that same year. After a test issue featuring a twenty year-old Jessica Simpson (blonde) cuddling her then boyfriend, obviously Nick Lachey, debuted in 2000, the magazine promised to be the anti–crush quiz fashion bible teen girls craved. For me, an all-girls-school attendee, it was welcomed and essential reading. But the magazine was published quarterly, and that left a void in the teen fashion landscape for months at a time. The July 2003 issue of Vanity Fair satiated some of that thirst. I became an absolute rabid animal in the hunt to get my hands on this issue. I was not, at fifteen, a Vanity Fair reader, nor should I have been, as the other cover lines of the issue previewed subjects far outside my interest—hard journalism about the Bush administration, a Hamptons real estate feature, and an author reporting on cold case murder facts—but the cover had been hyped up on all my favorite entertainment news programs, and I was intimately familiar with every single one of those teen girls’ faces. I was gently conditioned to already believe these adolescent women were goddesses. In fact, my younger sister and I were such dutiful consumers of all Mary-Kate and Ashley products that, to this day, I refuse to buy anything from The Row, their clothing line, as a twisted attempt to get justice for the money I have already shelled out to them.

You may have noticed that all the girls, now women, featured on that Vanity Fair cover are white, and I am not. More specifically, they are all thin, blonde, white girls. Even Mandy Moore, who had an edgy brunette cut at the time of the shoot, had been introduced to the world as a sugary-sweet blonde. No matter what her colorist mixed up, that was how many people still viewed her.

It seems like no accident that the brunette, the bad girl, the redhead, and the lone Black girl were conspicuously absent on the actual cover, instead relegated to the foldout. Alexis Bledel played the smart, safe, and overly anxious Rory Gilmore on Gilmore Girls. Evan Rachel Wood starred in the chilling 2003 film Thirteen, which was about suburban girls who rebelled by getting tongue piercings and having threesomes. Raven-Symoné, a Cosby Show alum, was now a Disney darling, the lead in an eponymous sitcom where she played a high schooler with psychic abilities. And Lindsay Lohan almost needs no introduction, but in 2003, she was not yet a Mykonos club hostess with a troubled family past. Rather, she was the girl who played both starring roles in The Parent Trap and was on the cusp of Mean Girls celebrity. Vanity Fair, like most publications at the time, was telling readers who deserved their attention. The inside story featured a more diverse set of “totally teens,” including Kyla Pratt, Christina Milian, and Solange Knowles, and was largely unmemorable. The cover is what everyone recalls. A magazine cover is a beacon, mesmerizing the reader with the image it presents. And for many years in fashion media, an upper echelon of publishing, we readers were shown white women and white women only. In the early part of the millennium, critical years of my development, if a coveted cover spot was assigned to someone, it was a blonde girl—extra points for a bony one.

"In the early part of the millennium, critical years of my development, if a coveted cover spot was assigned to someone, it was a blonde girl—extra points for a bony one."

Ignoring the presence of Black women is a massive power flex that exposes the ideologies of the decision makers who determine what celebrity is worthy of a feature. Erasure is a useful tool of oppression, and Vanity Fair was not alone in ensuring the erasure of Black women and girls from positions of prominence and honor. The media’s compounded interest in either strategically or accidentally reducing the visibility of Black women across the board poisoned my mind for years.

Raven-Symoné must have felt incredibly lonely shooting that Vanity Fair cover. To my knowledge, she’s never spoken about it. She has met some controversial moments in more recent years, relating in particular to her identity as a Black woman. In 2015, she became a trending topic after her criticism of ethnic Black names on the morning talk show The View went viral. Raven and her cohosts opined on whether racial bias affects hiring probability by way of recruiters screening the names of candidates. (Spoiler: It does.) Raven said that she would not hire a woman with the name “Watermelondrea” when that name appeared as number twelve on a list of “sixty of the most ghetto-sounding names.” And while hers was an ignorant and harmful comment, I do not think it is a surprising one from a Black woman who seems to me to have been coerced to maintain a degree of self-hatred, one that was ingrained and then nurtured by an environment that prioritizes whiteness in all forms.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Excerpted from Token Black Girl: A Memoir by Danielle Prescod. © 2022 Published by Little A, October 1st 2022. All Rights Reserved.

Brooke Knappenberger is the Associate Commerce Editor at Marie Claire, where she specializes in crafting shopping stories—from sales content to buying guides that span every vertical on the site. She also oversees holiday coverage with an emphasis on gifting guides as well as Power Pick, our monthly column on the items that power the lives of MC’s editors. She also tackled shopping content as Marie Claire's Editorial Fellow prior to her role as Associate Commerce Editor.

She has over three years of experience writing on fashion, beauty, and entertainment and her work has appeared on Looper, NickiSwift, The Sun US, and Vox Magazine of Columbia, Missouri. Brooke obtained her Bachelor's Degree in Journalism from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism with an emphasis on Magazine Editing and has a minor in Textile and Apparel Management.