How One Woman's Sexual Abuse Resulted in Years Behind Bars

She's just one of thousands of women caught in the sex abuse to prison pipeline.

Keisha B. was 14 years old when she reported the sexual abuse to the police. It had happened for as long as she could remember. The abuser was Keisha’s own father.

Keisha grew up in Queens, New York, in a two-parent, middle-class household. Her mother was a keyboard specialist and her father a mechanic who owned two body shops. While Keisha’s life appeared normal from the outside, her parents were alcoholics and her father regularly sexually abused Keisha and her older sister.

After going to the police, Keisha was put in foster care. But she ran away from three different foster homes to be with her mother, even though she was still with Keisha’s father. Keisha couldn't understand why she had to live with strangers.

Her father’s case went to trial. Ultimately, he was found guilty but not sentenced to jail. He was ordered to stay away from Keisha. He did not. He returned to the home he had shared with Keisha’s mother; the one where Keisha was once again living full-time.

To deal with the sexual abuse at the hands of her father, Keisha self-medicated with drugs that “made her forget.”

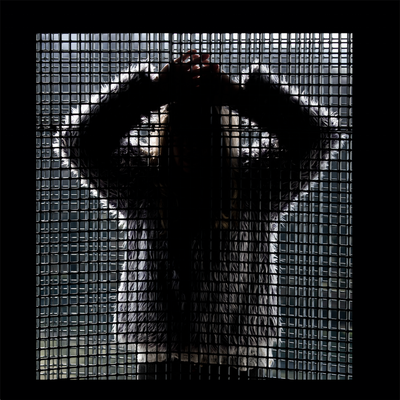

The abuse stopped, but the psychological torture of living with her abuser drove Keisha—a once-promising student—to act out. “I was so isolated from everyone for so long when the abuse happened,” Keisha says. “Once I reported him, I felt like a caged animal being released. But then the abuse I suffered was tossed to the side, because he was still allowed to remain in the house.” Keisha began to skip class. She was sent to a truant school, but eventually stopped going altogether. She smoked weed frequently. One day, she was given weed that made her feel like nothing had ever made her feel before. It was laced with crack. An addiction was born.

To deal with the past sexual abuse at the hands of her father, Keisha self-medicated with crack cocaine. The drugs “made her forget about all the stuff [she] was going through.” Soon, everything Keisha did was because she needed money to buy drugs. She needed money to feed the addiction. She needed the addiction to numb the pain. At 18, Keisha and her friends entered a house that was being renovated. She didn’t steal anything, but the police came and she was arrested and charged with burglary. But she didn’t show up in court; instead, Keisha began to prostitute herself in order to buy drugs.

The transition from a life of abuse to a life of crime isn’t uncommon. Women are the fastest growing prison population in the United States today, with women’s imprisonment skyrocketing 834 percent over 40 years. Many of these women were sexually abused before they got there: One 2006 Oregon study found that 96 percent of juvenile female prisoners were sexually abused prior to entering prison, and according to a 2009 study out of South Carolina, 84 percent of delinquent girls reported a history of sexual violence. Women in prison are twice as likely to report childhood sexual or physical abuse than women in the general population, and, of women currently incarcerated nationwide, 37 percent say they were raped before entering state prison. It’s a phenomenon known as the sexual abuse to prison pipeline—women react to their abuse with illegal activities and, rather than receiving support to help them break the cycle of behavior, they are sentenced to jail—and its existence is contributing to the booming growth of female prisoners today.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

According to a Vera Institute Study, “between 1980 and 2009, the arrest rate for drug possession or use tripled for women” (comparatively, the arrest rate for men doubled). “By the early 2000s, 50 percent of women in jails were in custody on public order [for example, prostitution, public drunkenness, or disorderly conduct] or drug charges.” For Keisha, substance abuse programs or social services to address her addiction were never an option—they were never offered to her. Fewer than half of the women in state prison who need the help of a substance abuse program actually get it, and receiving counseling for psychiatric issues is even less common. Prison isolates these women from their communities and creates obstacles so challenging that, when they finally get out, relapse feels inevitable.

Keisha’s next arrest came just a year later—for selling drugs. When she was arrested, her mother went to see her and couldn't believe her eyes. It was the first time she had seen Keisha in months because Keisha was living on the streets. Keisha was under 100 pounds—drastically thinner than she had ever been in her adult life. Keisha remembers her mother saying that the “spirit was sucked out of her.”

Keisha’s burglary case also caught up to her, but was downgraded from a felony to a misdemeanor trespass charge. For both cases, she was sentenced to six months of jail and five years of probation. She did her sentence and returned home to her mother…and her father. Two months later, Keisha started using again.

center']Of women currently incarcerated nationwide, 37 percent say they were raped before entering state prison.

For many women, prison time does not address underlying trauma, and, in fact, only serves to exacerbate it. Women in prison face deplorable conditions: Their mental health issues are rarely addressed (32 percent of incarcerated women suffer from mental health issues, almost double the rate of men), and female prisoners are also disproportionately sexually abused—women make up one-third of all reports of abuse by prison staff, despite comprising just 7 percent of all inmates.

For Keisha, the trauma continued untreated and, coupled with more personal tragedies, Keisha returned and returned to prison. At 20, she had a near-death experience: After suffering from sharp stomach pains, she found out she was six-weeks pregnant and that the fetus was forming in her fallopian tube. She had emergency surgery and a blood transfusion. “I was told I could not have kids, and I was told I was HIV-positive,” Keisha recalls. But no one seemed to care. “There was no counseling and no help.”

Within three weeks of the surgery, Keisha was using again. “I relapsed because I went back to what I knew would comfort me,” she says. “I felt at that point, drugs were all I had.” Keisha was arrested soon after for selling drugs and was sentenced to two to four years in prison upstate.

For the next few years, Keisha was in and out of jail for parole violations. Mostly, her urine was dirty from her drug relapses. Then, Keisha’s mother passed away. “My mother always said I could do anything I wanted. But suddenly she died. She was here today and gone tomorrow. She did not tell anyone she was sick. She was only 53. I needed her,” Keisha recalls. “My anger at the situation led me to relapse. I gave up on myself.” That year, Keisha picked up her second upstate bid, serving three to six years for prostitution.

The cycle continued: Keisha would get clean for a period, before relapsing due to job insecurity, abusive relationships, or, of course, her ever-present childhood trauma. She says she was never given the opportunity for counseling or therapy. She remembers that “there was no plan for me when I left prison. If I did not figure something out for myself, I would be back on the streets using again. Most women ended up in shelters and relapsed.” Finally she decided, “that was not going to be me.” Before leaving prison in 2010, Keisha secured services and housing for when she was released, beginning her “journey towards change,” as she calls it.

The trauma continued untreated and, coupled with more personal tragedies, Keisha returned and returned to prison.

Through a friend, Keisha found out about The Women’s Prison Association, an organization in New York City that provides services to women as they leave prison and re-enter their communities, and applied for programming on her own. Her time there was integral to her effort to kick her drug addiction and get her life back on track, she says. But the programming came late in Keisha’s journey. It was only after years of incarceration that Keisha was offered real, tangible therapy that helped her understand and cope with her trauma, therapy that helps address the specific trauma women like Keisha face. (Gender-responsive trauma-informed counseling has been shown to be successful in reducing the self-destructive behaviors women adopt in response to abuse.)

Ideally, therapy, counseling, and other services would address the trauma these women face before they become involved in the criminal justice system. Providing proper resources to Keisha in the immediate aftermath of her trauma may have prevented that first arrest—and the many that followed.

“As a society, we prefer punitive responses to crime over constructive, community-driven responses to harm,” says Georgia Lerner, executive director of the Women’s Prison Association. Punishment-based systems, like prison, don’t address the underlying causes of criminal activity and result in a high rate of recidivism. Even when ensnared in the system, alternatives to incarceration programs—which focus on treatment—would have been better, but, says Lerner, these programs tend to be underutilized. “I’d love to see us moving away from ‘alternatives’ to incarceration and focus on front-end, pre-arrest efforts to ensure public safety,” says Lerner. “This means that we would stop criminalizing women—and men—for being poor, sick, or hurt.”

Keisha estimates she was arrested more than 15 times, but has lost count. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent to incarcerate her. What if that money had been used instead to provide Keisha and other women like her with adequate resources to deal with her trauma? Keisha believes that had she had the help she needed to deal with her trauma early on, her whole life would have been rewritten. But now, she has made peace with her old wounds; after decades of blaming herself for the abuse, Keisha knows it was not her fault.

After programming and therapy, Keisha is no longer using drugs. She’s in school studying computer skills, and she is thriving. “I value my freedom much more than jail,” she says. “After therapy, I learned that the pain and consequences of drugs outweighed the pleasure. I learned how to manage my feelings. I did not learn it overnight, but what is important is that I learned it. I just wish it had happened sooner.”

Yosha Gunasekera is a public defender working in New York City and an expert on criminal justice issues. Her writing has appeared on Teen Vogue, The Huffington Post, and The Hill, among others.