It's Time to Talk About the Media's Role in Rising Suicide Rates

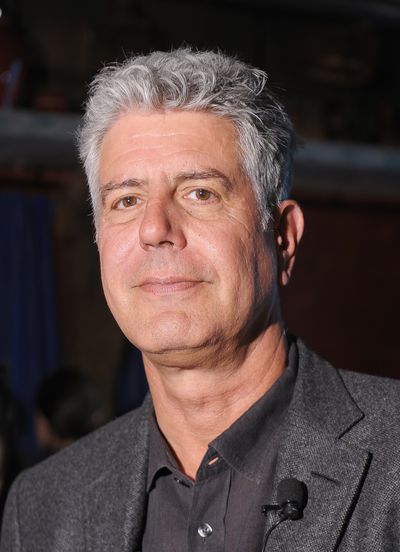

Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain both died by suicide this week. Suicide rates are rising, and media coverage of it, from '13 Reasons Why' to publicized details, feels even more problematic.

On Monday, June 4, iconic designer Kate Spade died by suicide at the age of 55. Four days later, chef, storyteller, and television host Anthony Bourdain died by suicide at the age of 61. These two losses, so close together, seem hard to articulate, and even harder to comprehend—but are also indicative of a systemic problem that is often overlooked. One person dies from suicide every 12.8 minutes in the United States. According to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suicide rates are up more than 25 percent since 1999. In 2015, 45,000 people died by suicide. It’s time we acknowledge the media’s role in all of it.

Our morbid fascination with death, and our collective reluctance to discuss it in any tangible, beneficial way, is nothing new. We pore over details of tragic losses of life, mass shootings, and unimaginable natural disasters, often to our own detriment. The media coverage of deaths by suicide has become so detailed that it can be argued that certain readers are surely affected. The frenzy of breaking news and reports, regurgitated during an endless 24-hour news cycle, leaves no proverbial stone unturned. The means by which the individual died by suicide are described in detail, despite recommendations on covering deaths by suicide that urge media outlets and reporters to do the opposite. As a result, readers are left with a vivid picture—one that could close the gap between suicidal thoughts and death by suicide.

Right now, suicide is the the third leading cause of death among young people ages 10 to 24. A reported 4,600 young people die by suicide every year, according to CBS News. In a 2017 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), per CBS News, “researchers reported a significant increase in emergency department visits for self-inflicted, non-fatal injuries among children and young adult.” Suicide rates among LGBTQ youth are even higher, and according to the Human Rights campaign, 30 percent of LGBTQ teens report having “attempted suicide” in the last year.

Seven years ago, a dear friend of mine died by suicide. And at my lowest point, I wanted to know every detail, every final action my friend took, as if it would somehow make me feel closer to him. But according to ReportingOnSuicide.org, more than 50 research studies worldwide have shown that obsessing over the details of a suicide isn’t healthy, and coverage of deaths by suicide can increase the likelihood of suicide in vulnerable people. In a recently released Pew Research report, it was found that almost seven in 10 Americans “feel worn out by the amount of news there is these days.” How deaths by suicide are covered, and discussed, is impacting the mental health and wellness of viewers, in a way that often isn’t noticed until it is too late.

In the four months after Robin Williams' death in 2014, suicide rates spiked by 10 percent, with a higher proportion using a copycat method than is typical. Coverage of Williams' death, much like Spade’s, was very detailed.

Not only are the estimated 300 million people, of all ages, genders, and ethnicities, who suffer from depression worldwide subjected to detailed coverage of celebrity deaths like Spade’s and Bourdain’s, they’re also presented with sensationalized and even romanticized depictions of suicide via television shows and movies. The Netflix show 13 Reasons Why, for example, positions suicide as a conduit for revenge, arguably reinforcing the idea that death by suicide is the only way for those struggling with mental illness to be seen, heard, and appreciated.

When today is over, 121 Americans will have died by suicide.

Of course, there isn’t any one reason why suicide rates are increasing. From a lack of affordable and accessible mental health resources, to mental health stigma, to a rise in hate crimes, we, as a nation, are failing those struggling with depression and suicidal ideation on multiple fronts—especially those in marginalized communities. But the relentless news cycle that provides horrendously detailed reports of deaths by suicide, coupled with problematic television programming that positions suicide as a romantic option, must be acknowledged for what they are: problematic at best, and dangerous at worst.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

When today is over, 121 Americans will have died by suicide. Most of us won’t know their names. They won’t trend on Twitter. They won’t be memorialized by celebrities and politicians and influencers. But like Williams and Spade and Bourdain, they, too, will be indicative of a cultural problem we want to ignore, but must face. We must acknowledge the way we’re making this problem worse.

If you or anyone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK).

This article has been updated.

Danielle Campoamor is Marie Claire's weekend editor covering all things news, celebrity, politics, culture, live events, and more. In addition, she is an award-winning freelance writer and former NBC journalist with over a decade of digital media experience covering mental health, reproductive justice, abortion access, maternal mortality, gun violence, climate change, politics, celebrity news, culture, online trends, wellness, gender-based violence and other feminist issues. You can find her work in The New York Times, Washington Post, TIME, New York Magazine, CNN, MSNBC, NBC, TODAY, Vogue, Vanity Fair, Harper's Bazaar, Marie Claire, InStyle, Playboy, Teen Vogue, Glamour, The Daily Beast, Mother Jones, Prism, Newsweek, Slate, HuffPost and more. She currently lives in Brooklyn, New York with her husband and their two feral sons. When she is not writing, editing or doom scrolling she enjoys reading, cooking, debating current events and politics, traveling to Seattle to see her dear friends and losing Pokémon battles against her ruthless offspring. You can find her on X, Instagram, Threads, Facebook and all the places.