Is Love Just an Illusion?

Freud thought so. Rilke thought so. Maybe single women do, too.

I'm reading an interesting book, Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession, written in 1980 by a New Yorker staffer named Janet Malcolm. She's teaching me a thing or two about Freud.

Freud's most original discovery, she argues, was the phenomenon of transference — which describes the human tendency to make our early relationships (like those with parents and siblings) into the blueprints we use for every subsequent relationship. As a result, we don't accurately "see" anyone after a certain point early in our development. Rather, we see them through the prism of the experiences we've already had.

As Malcolm puts it: The concept of transference at once destroys faith in personal relations and explains why they are tragic: We cannot know each other...We cannot see each other plain.

As Freud observed, when a patient is in psychoanalysis, he or she will often transfer certain feelings onto the analyst. Sometimes those can be feelings of anger or frustration or distrust. Sometimes, they're even feelings of amorous love — perhaps it has something to do with already being horizontal. The solution? He would explain to his female patients that the love they felt for him was a normal part of the treatment, but also something unreal and hallucinatory.

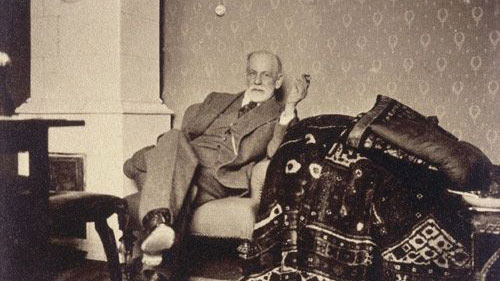

[image id='d7ef74ca-e70a-4069-8030-42472e68d356' mediaId='8745a362-8c8e-4b03-8f39-5bfd1cb0b1cf' loc='C'][/image]And in a 1915 paper, Freud went on to propose that all romantic love is like that — unreal and hallucinatory.

As Malcolm writes: Isn't what we mean by "falling in love" a kind of sickness and craziness, an illusion, a blindness to what the loved person is really like, a state arising from infantile origins?

Because I'm something of a cynic, maybe, I tend to agree with this view. So would the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, I suspect — he wrote that lovers "keep on using each other to hide their own fates."

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

All the same, if love is an illusion, it's a helpful one.

Why is it helpful? As Nietzsche points out in The Birth of Tragedy, the ancient Greeks developed their wonderful myths because the idea that superior beings — also known as the Gods — were suffering through stuff that was similar to what the mere earthlings were going through (like cheating husbands, vindictive wives, deceitful relatives, unrequited love, and all the rest) made it a little easier to take. Now, turn that around: If we can believe the idiots we love are godlike, it helps us put up with their BS — and also helps us think our lives are meaningful and wonderful.

Which is to say: We make up stories — about gods and about the people in our lives and about ourselves — to help us make life bearable.

"BUT MAURA!" I'm sure you're saying. "How do you explain happy marriages that last for years and years? That can't simply be an illusion!"

My answer? Maybe they're just two people with compatible illusions.

All right, folks: lay it on me. I have a feeling this is going to piss some people off, so if it annoys you, I am standing by, waiting to be corrected.

xxx!

PS: It's funny, but I sometimes think this whole illusion paradigm relates to why I've had such a hard time with love.

Hemingway said that to be a decent writer, one needs a built-in, foolproof shit detector — and I like to think I have that. So anytime that any person has started to express feelings of great affection for me, I've thought: "You're a complete idiot. You have NO IDEA WHO I AM. Whatever you like about me is much more about you — and who you think I am — than it is about the real me."