The Real Story of the Battle of the Sexes

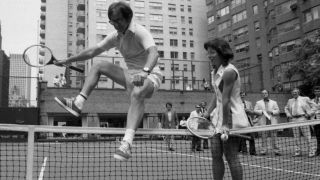

Billie Jean King on the match that made history—and headlines all over again with this weekend's big-screen premiere.

Billie Jean King had already played some big tennis matches in her career—49 grand slam finals, in fact—but when she walked onto the court on September 20, 1973, there was more than just $100,000 of prize money on the line. The fate of the whole women's movement was at stake. At least that's how King felt: "The pressure was unbelievable," she says of the match that became known as "the Battle of the Sexes"—and that came to represent, all in one immensely charged event, the entire struggle of women's equality. "We were fighting so hard to change hearts and minds about the value of women in society. I felt like everybody was depending on me to beat him."

Him was Bobby Riggs, a former world number-one with six grand slam titles to his name. Riggs had retired from the sport 14 years earlier and spent his post-playing days hustling the country club set. A shameless self-promoter and showman, his stunts included playing tennis while carrying a bucket of water or while chained to a baby elephant. Riggs was a proud chauvinist during the dawn of women's liberation and, in early 1973, he drew national attention by announcing that even at age 55 he could still defeat the best female tennis players in the world. In May of that year, he made good on that promise by beating the world's reigning number one, the legendary Australian player Margaret Court.

Riggs had approached King—who in 1972 had won the French Open, Wimbledon, and U.S. Open—about a match before he went to Court, but King turned him down, reasoning that it was a ridiculous sideshow with little upside. King considered herself a feminist, but understood that gaining equality wasn't about pitting genders against each other: "My brother and I were always close, and my parents were good to each other," says King. "I never understood it to be that one gender was better than the other. Feminism has nothing to do with not liking guys—a guy created the term!" But after Court's humiliating loss to Riggs, King changed her mind.

In the movie version of the match, Battles of the Sexes, out September 22 and starring Emma Stone as King and Steve Carrell as Riggs, the two are portrayed as old chums. But in reality King says she did not know Riggs well. The former star was 25 years her senior; he'd retired from professional tennis when King was just six.

"We were fighting so hard to change minds about the value of women. I felt like everybody was depending on me to beat him."

She'd read all about him, of course, and had seen footage of him in action winning the men's singles, doubles, and mixed-doubles titles at Wimbledon in 1939. As a child, everyone King encountered at the Lakewood Country Club in Long Beach, California—where she grew up playing—seemed to have a story about the enfant terrible Riggs, also born and raised in Southern California. But that was the extent of their relationship.

The two months leading up to the match versus Riggs were excruciating for King, who kept up her commitment to play on the WTA, the new women's tennis circuit she had helped found a few years earlier. She could only train for the "Battle of the Sexes" in her spare time. Weeks before the match, all the extra exertion took its toll: She fell ill with the flu and was forced with withdraw from a WTA tournament.

On the day of the match, King faced yet another hurdle before even taking the court: That afternoon she had an interview with television commentator Frank Gifford, who asked if she considered herself a feminist. "I had to think fast, because even though I love the word, it's a loaded word," says King. "And so I said 'I'm for the women's movement.'"

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

"Ninety million people were watching. If I had said I was a feminist, it would have been over," King explains. "Men hated the term. A lot of women hated it too. Semantics are powerful. I wanted to say something that represented my values but not lose everybody in the process. Still, if you watch the tape I'm talking softly. I didn't yet have my voice. I felt like I was on a tightrope."

"If I had said I was a feminist, it would have been over. Semantics are powerful."

As she tells it, the reason King had not yet found her voice is that her life was "so off-balance." She had been married to her husband, Larry, for eight years, and loved him, but had recently begun an affair with her hairdresser, Marilyn Barnett, the first woman she was ever romantically involved with. In a pivotal scene in the movie, in fact, Barnett visits King in the locker room just minutes before her match with Riggs and gives her a haircut. (In reality, King says the haircut did happen, but not then—it took place before she left Los Angeles for Houston.)

"You have to understand—my parents were from the Depression. They were good people, but they were homophobic," King explains. "We didn't talk about my sexuality. I was suffering so much." Barnett and King continued their affair for several years. "Larry never wanted to divorce," says King, who remained married to him until 1987. "I still love him," she says. "Life can get messy."

Thirty-two thousand, four hundred and seventy-two people turned up to the Houston Astrodome to see the "Battle of the Sexes"—a crowd that remained the largest on record for a tennis match until 2010. Four bare-chested men dressed as Roman slaves carried King onto the court that night (something she found funny, she says). Riggs followed in a rickshaw pulled by half-naked models.

King says she was too nervous to look up to the rafters and take in the crowd. She knew her parents were there, which made it a meaningful match regardless of who she was playing: Her father, Bill Moffitt, was a Long Beach firefighter who rarely left his post; he and King's mother, Betty, typically only watched matches she played in Los Angeles. They traveled to Wimbledon just once in the 21 years King competed there. King eyed the crowd for a split second and spotted her friend Pam Austin holding up a sign that read, "BYE BYE BOBBY." The familiar sight was comforting. "I noticed her because she had curly hair," King says. "Pam became my anchor in a war."

King walked to the baseline in a white and blue outfit she helped design, and blue tennis shoes. (The ensemble is now on display at the Smithsonian.) Riggs wore tennis shorts and a polo shirt, and began the match wearing a bright yellow and red jacket that advertised Sugar Daddy. The candy company had paid him $50,000 to wear it. King says she wasn't wearing any endorsements because she wasn't offered any. She still remembers how Time magazine put Riggs on its cover a week before the match…without her.

"We didn't talk about my sexuality. I was suffering so much."

King fell behind in the first set four games to two. But instead of folding like Margaret Court had months earlier, the early setback only resolved her determination to win. "The movement had come so far. We had just passed Title IX the year before," she says. "From the time I was 11 years old I wanted to be the best tennis player in the world, because I knew that was how I could make a difference. All I could think about was that all the struggle of the movement would be for nothing if I lost. I had no other choice. I had to win."

As King's focus became more intense, Riggs' began to wane. She had planned to play conservatively, staying on the baseline and making Riggs run back and forth to tire him out. It worked. She took the first set 6-4. Riggs ditched his jacket. She took the second set 6-3, but still wasn't sure she would win. Women's matches are best of three—this match was best of five. King knew the quickest way to defeat was to start daydreaming about the trophy presentation. "I always tell everybody: It's not over until you're shaking hands at the net," she says.

Though she refused to get ahead of herself, King could feel Riggs' fatal mistake with every ball he hit her way: He had treated this as a sideshow; she had taken it seriously. Her father had always told her that the easiest way to lose was to underestimate your opponent.

King won the third and final set 6-3 and threw her racket to the sky. When she shook hands with Riggs at the net following the victory, he leaned in and said: "You know, I really underestimated you."

"I went and found my dad and said, 'Dad! You won't believe what he said,'" King exclaims. "What did I tell you?" her father replied.

In the four decades since the match, King has heard the inevitable rumors that Riggs let her win, including recent claims that he fixed the match to pay off gambling debts he owed to the mafia.

She laughs them off. "There were rumors that maybe we were playing with different rules," King says. "But you have to understand: By that point he was 55 years old and I was 29. We played straight-up. The battle was always going to be more psychological than physical. I was just tougher that day."

Follow Marie Claire on Facebook for the latest news, long reads, video, and more.

Molly Knight wrote about baseball for ESPN the Magazine for eight seasons. Her work has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Glamour, SELF, Vanity Fair, Baseball Prospectus, and Variety. Her first book, The Best Team Money Can Buy: The Los Angeles Dodgers Wild Struggle to Build a Baseball Powerhouse, was a New York Times Bestseller.

-

Katie Holmes Tames an Underrated Animal Print Trend

Katie Holmes Tames an Underrated Animal Print TrendTiger is the new leopard.

By Kelsey Stiegman Published

-

Taylor Swift's Beloved Red Lipstick Is Finally Back in Stock

Taylor Swift's Beloved Red Lipstick Is Finally Back in StockIt's been a long time coming.

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

I Move Up a Tax Bracket Every Time I Wear This Opulent Manicure

I Move Up a Tax Bracket Every Time I Wear This Opulent ManicureBonus: you can achieve the look with $15 press-on nails.

By Samantha Holender Published

-

Julia Roberts Turned Down a 'Notting Hill' Sequel, Calling It a "Very Poor Idea"

Julia Roberts Turned Down a 'Notting Hill' Sequel, Calling It a "Very Poor Idea"Hugh Grant is ready to destroy the movie's happy ending, though.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Jude Law Devastates 'The Holiday' Fans by Revealing a Secret About the Film's Idyllic English Cottage

Jude Law Devastates 'The Holiday' Fans by Revealing a Secret About the Film's Idyllic English Cottage"Just burst the bubble. Sorry!"

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

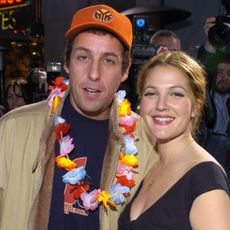

Drew Barrymore Discovered Her Daughter Watching '50 First Dates' with Adam Sandler's Daughter

Drew Barrymore Discovered Her Daughter Watching '50 First Dates' with Adam Sandler's Daughter"They were just so happy and I was like, 'Oh, but this is so sweet and wonderful.'"

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Actors Who Are Nothing Like Their Most Iconic Characters

Actors Who Are Nothing Like Their Most Iconic CharactersTalk about awards-worthy, transformative performances.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Joe Alwyn Says He's "So Lucky to Be Close" to Taylor Swift's Pal Emma Stone

Joe Alwyn Says He's "So Lucky to Be Close" to Taylor Swift's Pal Emma StoneThey've starred in two movies together.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Emma Stone Is Visibly Delighted to Be Called by Her Birth Name in Cannes

Emma Stone Is Visibly Delighted to Be Called by Her Birth Name in CannesShe loves being called Emily.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Emma Stone Says She Wants to Be Known By Her Birth Name from Now On—Not Emma, Her Stage Name

Emma Stone Says She Wants to Be Known By Her Birth Name from Now On—Not Emma, Her Stage Name“That would be so nice.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Did Emma Stone Call Jimmy Kimmel a Pr—k? An Investigation

Did Emma Stone Call Jimmy Kimmel a Pr—k? An InvestigationSocial media lip-readers seem to think so.

By Meghan De Maria Published