It's been 43 years since Roe v. Wade gave women the right to abortion, but that right faces more opposition today than ever.

More abortion restrictions have been enacted in the last five years than in any other five-year period since 1973, the year the case was decided. Already in 2016, 21 new restrictions have been made law in five states: Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, South Dakota, and Utah. The Supreme Court is considering a Texas case that could put clinics across the country in danger of closing if it expands the standard of "undue burden" by upholding the state's surgical facilities and admitting privileges requirements.

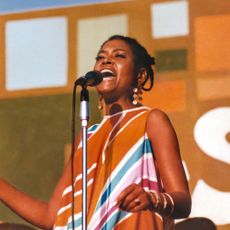

These developments are reported on frequently, but to filmmaker Tracy Droz Tragos, the women in states impacted by increasingly prohibitive laws are the ones being left out of the debate. Her new documentary Abortion: Stories Women Tell sets out to give some of them a platform, featuring dozens of women who voice their abortion experiences.

The film, coming soon to HBO, premiered at Tribeca Film Festival last week, where Marie Claire spoke with Droz Tragos about the making of her powerful documentary, and the impact she hopes it will have.

Marie Claire: What inspired you to make Abortion: Stories Women Tell?

Tracy Droz Tragos: It started with a conversation with Sara Bernstein, a senior producer at HBO Documentary Films. We wanted to make a film about abortion that was different, that really focused on intimate, personal women's stories. We wanted to hear from voices that weren't being heard.

MC: How did you find the women and choose whose stories to tell?

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

TDT: Well, we focused on Missouri. Missouri is my home state, and for me as a filmmaker, it always helps to start from a familiar ground. Missouri is also one of the most restrictive states in the country when it comes to abortion and what's happening there is largely uncovered by the press for whatever reason. There's all this focus on Texas, and not a lot of the stories from Missouri are on the national consciousness. I started filming on the eve of this 72-hour waiting period that passed and is now law in the state. It made sense to start there and to hear these stories.

MC: Most of the women in the documentary are sympathetic from the perspective of having a pregnancy that was either immensely difficult or impossible, whether it was an abusive partner or a health defect or a financial situation. Was that a conscious decision you made?

TDT: No, it was not a conscious decision. I think consciously we wanted to hear from women who had as many different circumstances as possible. One of the challenges in the editing room was how to have the film cover all the different perspectives and circumstances that women face.

MC: What were the biggest challenges of making the documentary?

TDT: Access. Approaching a woman on the day of her abortion procedure to share her story is a big ask and certainly not something that all patients want, especially in Missouri where there's such a climate and context of shame and stigma. Why would anyone be public about that when they're already feeling so stigmatized? But there were women who wanted to come forward. Every woman I spoke with talked about other women in their same circumstances, women that they wouldn't meet or know, but perhaps in sharing their story, these other women would have some comfort and not feel so alone and stigmatized in the way the women who were sharing their stories felt.

MC: A lot of the women talked about abortion for themselves in one way — they say it's necessary and beneficial and that they have no regrets — but then they also seem to feel a lot of shame from the stigma you mention. What did you make of that?

TDT: Yeah, the shame was posed from the outside, and I think because of that, there's really a sense of not being able to talk about it. For [documentary subjects] Aimee and Monique, who got to share this with an audience at the premiere, there was such an outpouring of women who came after the screening and talked to them. They felt so embraced and empowered by that experience, and I just hope we can get to a place where exit's okay to share your story, you know? And that lots of women are doing it.

MC: Almost all the women in the documentary, including the women working at the clinic and even some of the pro-life women, had some sort of experience with abortion. Did you set out to show the universality of it, or did it happen unexpectedly?

TDT: That's the reality of it, you know? It really is like, your mother, your sister, your niece, your daughter. I mean, it's many, many women from all walks of life having abortions. And they have abortions whether they're pro-life or pro-choice. What I saw in making this film was that when all these state restrictions come down, the women who are affected the most are low income women. The 72-hour waiting period in Missouri means lost work and lost wages, and the effect of that is pretty sever and unfair.

MC: How did the clinic protestors respond to your filming?

TDT: They're there to be in the spotlight and to make noise. The day we were focusing on the clinic escort Deborah, one the protestors was unavoidable. When we were wanting to sit with the guard Chichi and have a quiet moment with her, he's there again. Even though that wasn't the focus of the film, it was very hard to not include because they were always there, and that was the final gauntlet that women had to pass through to access the care they needed.

MC: What do you think is driving the pro-life's movement increased efforts to restrict abortion in the past five years?

TDT: I wish I knew. I couldn't say, but it is a reality, and it is a reality that deserves some attention. Even though abortion is still legal, it is becoming increasingly inaccessible, and rights are being eroded.

MC: What do you hope viewers will come away with?

TDT: I hope the film gives an invitation to empathy, to think more about women who are affected, to think more about the individual and personal circumstances that women face. And that it resonates in a personal place for viewers and gives something that perhaps can shift the conversation from rhetoric to a more personal, compassionate place, no matter whether you consider yourself pro-life or pro-choice, that there's more compassion in the conversation.

Follow Marie Claire on Facebook for the latest celeb news, beauty tips, fascinating reads, livestream video, and more.

I'm the features editorial assistant at Marie Claire. Before working at MC, I spent time in the production department at The New Republic and writing about politics for Bustle. When I'm not writing, you can find me museum-hopping, practicing mediocre yoga, and stalking pugs on Instagram.

-

Dua Lipa's Coquette Chanel Gown Took 1,000 Hours to Make

Dua Lipa's Coquette Chanel Gown Took 1,000 Hours to MakeAnd yes, there's a bow.

By India Roby Published

-

Sources Close to Kylie Jenner and Timothée Chalamet Are Finally Addressing Those Baby Rumors

Sources Close to Kylie Jenner and Timothée Chalamet Are Finally Addressing Those Baby RumorsThe gossip surrounding the famous couple has hit a fever pitch.

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Emma Stone Says She Wants to Be Known By Her Birth Name from Now On—Not Emma, Her Stage Name

Emma Stone Says She Wants to Be Known By Her Birth Name from Now On—Not Emma, Her Stage Name“That would be so nice.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Documentaries About Black History to Educate Yourself With

Documentaries About Black History to Educate Yourself WithTake your allyship a step further.

By Bianca Rodriguez Published

-

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We KnowNetflix owes us answers after that ending.

By Zoe Guy Last updated

-

'Firefly Lane' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Firefly Lane' Season 2: Everything We KnowIn the immortal words of Tully Hart, "Firefly Lane girls forever!"

By Andrea Park Published

-

31 Different Pride Flags and What Each Stands For

31 Different Pride Flags and What Each Stands ForInclusivity matters.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

'Bridgerton' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Bridgerton' Season 2: Everything We KnowThe viscount and his new love interest hit Netflix at the end of March.

By Andrea Park Published

-

'Bachelor In Paradise' 2021: Everything We Know

'Bachelor In Paradise' 2021: Everything We KnowIt's back, baby!

By Andrea Park Published

-

In 'We Are Not Like Them' Art Imitates Life—and (Hopefully) Vice Versa

In 'We Are Not Like Them' Art Imitates Life—and (Hopefully) Vice VersaRead an excerpt from the thought-provoking new book. Then, keep scrolling to discover how the authors, Jo Piazza and Christine Pride, navigated their own relationship while building a believable world for Riley and Jen—best friends, one Black, one white, dealing with the killing of an unarmed Black boy by a white police officer.

By Danielle McNally Published

-

Love Has Lost

Love Has LostQuasi-religious group Love Has Won claimed to offer wellness advice and self-care products, but what was actually being dished out by their late leader Amy Carlson Stroud—self-professed “Mother God”—was much darker. How our current conspiritualist culture is to blame.

By Virginia Pelley Published