I got pregnant when I was 19, and in love, and having the sort of constant, frenzied, and, yes, unprotected sex that many in early adulthood know not to engage in but engage in anyway. (I would become pregnant again at 24 and at 27.) The first termination took place at a Planned Parenthood in downtown Sacramento, and I was terrified but resolute: There had never been any doubt in my mind as to whether I would go through with the pregnancy, and little concern as to whether I might later regret it. I didn't, and I didn't regret the next abortion, or the next one, although I did marvel, in later years, at the fact that had I taken these pregnancies to term, I would, at 35 years of age, be a mother to, respectively, a 16-year-old, a 10-year-old, and an 8-year-old. I found the idea utterly, completely terrifying.

That utter horror had very little to do with my feelings about children and everything to do with my feelings about myself—namely, my hunger to do things, and meet people, and carve out a special space in the world in which I could find my authentic self, whatever that came to mean. Motherhood had never been of particular fascination for me—from the time I was a young girl until well into my 30s, I did not fantasize about having babies or find others' babies of much, if any, interest.

Part of this was, no doubt, a function of the 1980s in which I was raised, a time when the birthrate of the United States was in the midst of a lull that had begun back in the mid-'70s economic recession. And though the country's conservatism was reflected, to some degree, in its popular culture, which still relied on depictions of functional, conventional, nuclear families, the female heads of households in those narratives—Clair Huxtable on The Cosby Show, Elyse Keaton on Family Ties, the eponymous heroines of Kate & Allie, to name some television examples—were more than just moms. They were also, for the most part, career women. As such, their fealty to their kids was profound but not prohibitive. They did not locate their successes, and certainly not their senses of self, within the comings and goings of the minors under their care. In fact, sometimes children of '80s-era television women were so ancillary to their mothers' identities as to be almost beside the point: After the high-powered Murphy Brown decided to give birth to a baby she would raise as a single mom, her son all but disappeared from the series writers' radar.

I don't believe I can do the things I want to do in life and also be a parent to kids.

Mothers who are able to successfully combine work and family are all around me, yet the compatibility of career and kids remains a concept I understand intellectually but seem emotionally unable to accept. And so when I tell people (usually female friends) that, at age 41, I "don't know" if I want children or still feel that I'm "not ready," what I'm really saying is that I don't believe I can do the things I want to do in life and also be a parent to kids, nor am I willing to find out. Fueling this tension is a deep and paralyzing fear not so much about children, but about my own latent caretaking instincts. I suspect I would be a good mother, a fantastic mother even, thanks to the gifts bestowed upon me by my own parents—the ability to give and express love, the indulgence of curiosity, and the prioritizing of imagination, education, and personal integrity over societally approved successes like financial or social achievement. But herein lies the rub: As it stands now, I suspect that my commitment to and delight in parenting would be so formidable that it would take precedence over anything and everything else in my life—that my mastery of motherhood would eclipse my need for, or ability to achieve, success in any other arena. Basically, I'm afraid of my own competence.

My therapist would describe this as magical thinking—and she might be right. But the example set by my own mother informs much about my decision to not have kids, and her story fills me with both pride and guilt. A skinny, curious Midwestern girl who escaped her insular, tiny Ohio town and headed east to New York City, where she earned the first of two graduate degrees, worked in social justice, and traveled the world, my mother found herself, a decade and a half later, trapped in an unremarkable suburb 10 miles west of Sacramento, teaching typing skills to snotty 13-year-olds and supporting two grumpy daughters desperate to be left alone in their rooms.

Is this the life she imagined for herself? My mother would no doubt take issue with what I've just written. She would flinch at the idea that her two children are anything but beautiful blessings, beings made from love between her and my adoring father, conduits through which she was able to channel all of her love, and to experience and further indulge her curiosity and wonder at the world. She would deny that she lost something of herself in motherhood. And though she might concede to having felt the occasional bout of frustration, maybe even acknowledge a relationship between child rearing and ambitions left unfulfilled, she would maintain that she had never communicated this to her children with any specificity. She'd be right. But my sister and I didn't need to hear our mother say how much parenting—much of it single parenting—limited her life; we saw it every day. We understood that by devoting her life to us, she was, in some ways, giving up herself. (As for my dad, well, let's be clear: This neglect of self in the service of children, while not wholly specific to women, is at the very least highly specific to them. Women have long been responsible for a disproportionate amount of the child care.)

Some might call my trepidation at the idea of motherhood "selfishness"—I would call it "agency"—but those people are probably either (1) dudes or (2) self-satisfied professional parents, and I'm not sure I care enough about their opinions that I wouldn't just agree with them and shrug my shoulders in shared chagrin. (Those who inquire after my plans for parenthood often interpret my childlessness as a dislike for kids, when nothing could be further from the truth.) But the fact is, it is never far from my mind that the means of reproduction—and its costs—are beasts of burden borne, historically, by the fairer sex. Times have changed, of course, and men shoulder more of the responsibilities of parenting than they used to (tethering themselves to Snuglis and BabyBjörns), but the demands on and expectations of women, at least in the highly educated and relatively affluent milieu I inhabit, have not so much disappeared as shifted to other things—namely, a set of insidious, though by no means unprecedented, expectations for the maintenance of outward appearances.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Becoming a mother would feel like a devolution as much as an evolution.

Nowhere are these hoary ideas about womanhood—this performance of perfect femininity—more routinely on display than on the streets of the South Brooklyn neighborhood where I live, lined with low-cal frozen yogurt shops and yoga and Pilates studios and overpriced boutiques filled with one-of-a-kind maternity clothes and hundred-dollar sets of receiving blankets made of "all organic cotton." One recent Mother's Day, I walked by an apparel shop displaying a sandwich board exhorting (presumably unintentionally childless) female passersby who felt sad about the holiday to buy a dress that would get them "knocked up in no time." Add to that the creeping commodification of childhood in the form of must-have status symbols—baby carriages, sleeper clothing—and the economic inequalities and educational failures that find parents signing up their toddlers for placement in private elementary schools years in advance, and you've got yet another reason for some of the aversion I have for the demands of modern American parenthood.

In the end, maybe my ambivalence about motherhood comes down to the fact that I just don't trust myself enough. (Or that I need to move somewhere far, far away from New York, to a place where kids can play safely in the dirt and grocery store aisles are blessedly free of $4 single-serve pouches of organic sweet-potato-and-pear puree.) But I believe that there is something else going on here, a societal discomfort not just with women who choose to remain childless, but with those who decide to become mothers and dare to confess to feelings of frustration and exasperation over the choices they have made. In the spring of 2014, just five months after becoming First Lady of New York City, Chirlane McCray was excoriated by city tabloids for having the gall to suggest that the arrival of her first child was celebrated with anything but complete and utter devotion. "I was 40 years old. I had a life," McCray told New York magazine. "But the truth is, I could not spend every day with her. I didn't want to do that. I looked for all kinds of reasons not to do it….But I've been working since I was 14, and that part of me is me. It took a long time for me to get into 'I'm taking care of kids,' and what that means."

What McCray left unsaid, but what I suspect she was also getting at, is that it often takes a long time for women to "get into" taking care of themselves, and that her need for autonomy was as much about basking in her hard-won self-actualization as it was a reaction to the exhaustion that comes with tending to a child's every need. These days, I find that I am only now beginning to feel comfortable in my own skin, to find the wherewithal to respect my own needs as much as others', to know what my emotional and physical limits are, and to confidently, yet kindly, tell others no. (No, I cannot perform that job; no, I cannot meet you for coffee; no, I cannot be in a relationship in which I feel starved for emotional and physical connection.) Despite (or because of) my single status right now, becoming a mother would feel like a devolution as much as an evolution, and the irony is that if and when I reach the point when I feel able to give my all to another human being and still keep some semblance of the self I've worked so hard to create, I will probably not be of childbearing age. Them's the breaks.

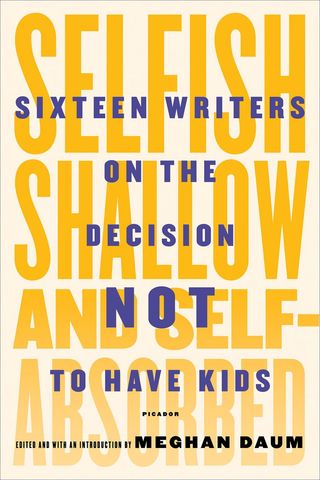

This essay appears in the forthcoming book

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids

, edited by Meghan Daum and published by Picador. Available March 31.

You should also check out:

Is Not Wanting Children a Deal-Breaker?

5 Things I'm Not Looking Forward to Explaining to My Future Children Because of the Internet

-

Selena Gomez Explains Why She Finds Leaving Instagram "Rewarding"

Selena Gomez Explains Why She Finds Leaving Instagram "Rewarding""I was more present. I was happier."

By Meghan De Maria Published

-

Kate Middleton Omitted This Word from Her Wedding Vows to Prince William So That, From the Start, They Would Be Seen as Equals

Kate Middleton Omitted This Word from Her Wedding Vows to Prince William So That, From the Start, They Would Be Seen as EqualsHer late mother-in-law, Princess Diana, had broken tradition and done the same in her own vows to Prince Charles 30 years prior.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

4 Summer Essentials Everyone Should Have in Their Closet

4 Summer Essentials Everyone Should Have in Their ClosetPerfect for Mother's Day, too.

By Nikki Ogunnaike Published

-

They're Single. They're Straight. They're Friends. And They're Having a Baby.

They're Single. They're Straight. They're Friends. And They're Having a Baby.You want a child. You don’t want to do it alone. What do you do? For an increasing number of women, the answer is raising a kid with their BFF.

By Sarah Treleaven Published

-

My Husband Left Me After 16 Years—So I Bought a Fixer Upper Across the Country

My Husband Left Me After 16 Years—So I Bought a Fixer Upper Across the Country"This house could hold me. It had survived being abandoned, too."

By Danelle Lejeune Published

-

A Decade ’Til “I Do”

A Decade ’Til “I Do”Darlena Cunha had been married for 10 years when she decided it was finally time to have a wedding.

By Darlena Cunha Published

-

5 Insane Stories of Family Drama Ruining Weddings

5 Insane Stories of Family Drama Ruining WeddingsBecause the Markles aren’t the only ones going through it.

By Megan Friedman Published

-

New Study Says Women Don't Really Care About Marriage or Baby Daddies

New Study Says Women Don't Really Care About Marriage or Baby DaddiesWhat even are men?

By Rebecca Gale Published

-

My Dad Is Dating a Woman My Age—and It Has, Weirdly, Inspired Me

My Dad Is Dating a Woman My Age—and It Has, Weirdly, Inspired MeAn emotional rollercoaster I wasn't expecting.

By Olivia Clement Published

-

How My Husband and I Went from Staunch Conservatives to Die-Hard Feminists

How My Husband and I Went from Staunch Conservatives to Die-Hard FeministsA faith journey of a different kind.

By Brandy Walker Published

-

I'm Done Apologizing for Keeping My Last Name

I'm Done Apologizing for Keeping My Last NameOh look, a soap box.

By Bridey Heing Published