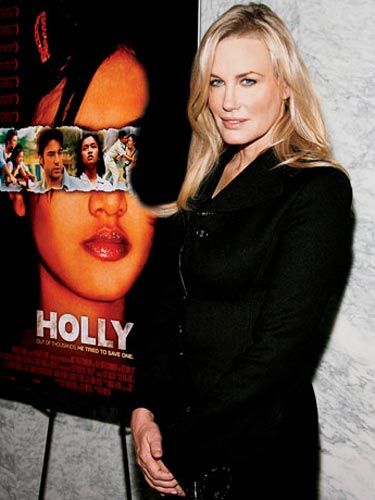

Daryl Hannah: Saving Sex Slaves

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daryl Hannah's latest role took a serious turn, blurring the boundary between acting and real life. For a documentary about sexual slavery, she snuck into the seedy brothels of Southeast Asia to meet the little girls who are held there. It's heartbreaking work, but Hannah is determined. Speaking at the United Nations in November at the launch of a foundation to fight sex slavery, she cited an alarming statistic — that there are more slaves in the world today than ever before — and vowed to help change that. She talked with Marie Claire's Abigail Pesta about what drives her.

Q: What sparked your interest in this issue?

A: About four years ago, I ran into a friend who used to be in the band Jane's Addiction. When I asked him what he'd been up to, he said, "Oh, I've been working on freeing slaves around the world." And my jaw just fell to the floor. I just was like, "What are you talking about?" I was raised in the Midwest and had a pretty normal background, but I don't consider myself completely sheltered. So from that moment, I thought, I have to find out what's going on and educate myself.

Q: So that's when you went to Southeast Asia?

A: Right. I went to Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos. But the problem is everywhere — in South America, the Eastern bloc countries, even in America — not only in Southeast Asia, where it's right out in the open. And then I started working on my documentary.

Q: Was it difficult getting into the brothels?

A: I basically had to do some of my best acting, because otherwise it could have been a dangerous situation. I had to play the part of a pervert; I'd go in with a guy, and we'd act like we were a couple looking for a kid. The pimps didn't question us — they would just show us everyone they had available. In some cases, they were 8-year-old girls sleeping on a couch with fluffy slippers.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Q: How did the girls react to you?

A: They were so affectionate with me, holding my hand or rubbing my shoulder. I kept thinking that most of these girls have not had any kind of affection since they were ripped away from their parents, and maybe not even before that, depending on what their family situation was like. So whenever the pimp wasn't around, I would just try to be goofy and make them giggle. The flood of tears that would come from the girls when I would do that was just shocking.

Q: What was the hardest part for you?

A: It eats me alive to see girls in that situation. If you knew there was a little girl living in the house next door to you, an 11-year-old who was kidnapped from her parents and was being held prisoner and raped 40 times a day, would you not run through your neighborhood screaming, "Help! We have to get her out of there!"? Would you not do everything in your power to help her? But because it's something that people don't recognize or can't relate to, they don't have that sense of urgency and panic. I hope my film will help — I'm finishing up the editing now.

Q: You recently joined the board of the Somaly Mam Foundation. Tell us about Somaly.

A: She's a former victim of sex slavery who now rescues girls across Southeast Asia. To me, she's got the greatest shelters, because most [others] are run by missionaries, and while their intentions are good, they do have a mission to spread their belief system. Somaly's shelters strictly help victims get their lives back.

Q: You had your own odd brush with sex slavery when you were a teen, right?

A: It was a completely different situation, and I didn't suffer, but what happened to me does illustrate how easy it is to prey on people. Basically I was 17 and had just moved to California for college. I was asked by some girls in the grocery store if I wanted to go with them to do a modeling job in Vegas. And I thought it would be a great way to make some friends, as well as some money. And I got there, and it just didn't seem right. Some guys put us up in a hotel, so already we owed them something. They had someone following us everywhere, even into the ladies room — everywhere. One of the girls had a cousin who was a detective, and he told her it was a sex-slave ring and to get the hell out of there, so we did. But if I hadn't been able to call my mom and say, "Help, I need a ticket," I would have been stuck there because I didn't have any cash.

Q: With three movies in the pipeline this year, how do you balance your activism and acting?

A: I really try as hard as I can — even if I have just a day off from work — to educate myself about human rights and environmental concerns, and then do what I can to pass that information on to others who might be inspired to act as well.

To learn more or to make a donation, go to somaly.org.

Abigail Pesta is an award-winning investigative journalist who writes for major publications around the world. She is the author of The Girls: An All-American Town, a Predatory Doctor, and the Untold Story of the Gymnasts Who Brought Him Down.