The Big Exit: How 3 Women Made Serious Bank by Selling Their Startups for Millions

Ca-ching.

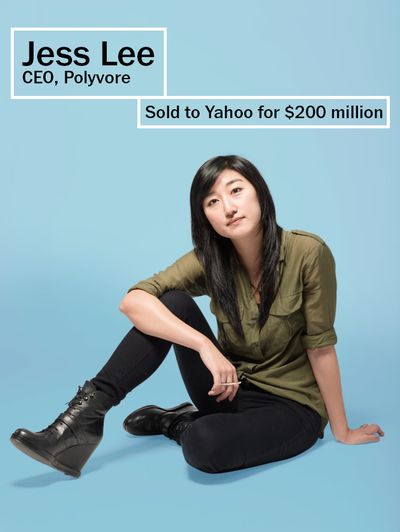

Jess Lee isn't a power-suit-wearing kind of executive. In the past year, the chief executive of Polyvore, the e-commerce site that lets the fashion-obsessed curate their own digital inspiration boards, has been spotted around the company's Sunnyvale, California, offices gamely dressed as Han Solo for a company Star Wars outing. Last year, she went to Comic-Con as a character from the Japanese manga Clover. "I love Comic-Con. It's like my mecca," she says.

Most days, though, Lee, 33, wears her own spin on Silicon Valley's laid-back uniform: black jeans and a white tee, punctuated by a brutal-looking barbell necklace she found on Polyvore, whose most crucial feature, arguably, is its shoppability. In that way, it is unique from rivals like Pinterest and Instagram, which have yet to nail down how to convert eyeballs into purchases to the same degree. In September 2015, Yahoo snapped up Polyvore—and its 20 million devotees—for a reported $200 million. The day Lee announced the deal was a career apex, she says. "To be able to look my team in the eyes and to know that all the blood, sweat, and tears was going to count for a meaningful outcome was really exciting."

To be able to look my team in the eyes and to know that all the blood, sweat, and tears was going to count for a meaningful outcome was really exciting.

Born in Canada and raised in Hong Kong, Lee says her mother, who ran a successful translation business, was a model for how to run a company. After graduating from Stanford, Lee was offered a job as a product manager at Google. She was hesitant, unsure if she could handle the responsibility. After all, Lee reasoned, she was a software engineer, not someone qualified to lead engineers. But she took the gig anyway, largely because of advice she'd received during one of her interviews, from Marissa Mayer, then a Google vice president: "She said she always chose the more challenging path because you would learn and grow the most."

That advice stuck with Lee when the founders of Polyvore approached her to join as product manager in 2008. (Four years later, they would tap her as CEO and confer her with founder status.) The company consisted of three people when she started but showed promise. Here, she thought, everything would be a challenge. In fact, after she signed on, it was Lee who secured new offices, built her own desk, and wrote her own code.

Lee's chief goal was to improve engagement and get users to spend more time noodling on the site. For Polyvore, that meant making the process of curating collages ("sets," as they're called) of outfits and trends easier and more fun. But in doing so, she was quickly confronted with the nuances of an ad-driven business. She had early success with a Nike ad campaign, but found that she couldn't replicate it with other brands. So she hired a "revenue expert" (yes, it's a job), who went on to pioneer a strategy of paid referrals—Polyvore gets paid for every user it refers to brands—which is now ubiquitous in social commerce: making brands pay to "sponsor" products to appear on the site in a more organic and editorial context. In 2010, before she took over as CEO, Polyvore users created 35,000 sets per day. Under her leadership, the number has nearly tripled. The average Polyvore customer spent about $160 in 2015, according to an AddShoppers study.

In a Silicon Valley twist of fate, Yahoo's acquisition of Polyvore means Lee finds herself again working for Mayer, now Yahoo's embattled chief executive. A couple weeks before Lee and I spoke, Yahoo had announced plans to cut 15 percent of its workforce, mostly affecting its editorial staff. "I think Yahoo is going through a difficult turnaround," Lee says. "The philosophy in that situation is: To do a few things well, you really have to simplify and focus."

Lee will continue to run the company under Yahoo. And she remains as hands-on as ever. (She personally wrote thank-you notes to every Polyvore employee after the Yahoo sale.) It's late February, and as we talk, Lee spots a dated Halloween link on the site. Instead of calling an engineer or sending an e-mail to one of her employees, she says, "I need to fix that," making a mental note. "I'll fix that tonight."—Lauren Steuss

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

These days, the buzziest startups all have in common Brew Media Relations, the PR firm of choice for the likes of Oracle, Refinery29, Jawbone, and the Samsung Global Innovation Center, an incubator within the tech giant. But to even get a meeting with Brew, you've first got to wow founder Brooke Hammerling. To be clear, she eschews conventional PR, with its press releases and media-courting gimmicks. Instead, she'll advise you on your long-term media strategy, everything from which talent to poach to which conferences to attend. "We work with the founding team, the executive, the CEO," Hammerling, 42, explains. "You're not leading strategy unless you're working with the executive team."

Raised in Westchester, New York, Hammerling graduated from Rollins College, a small liberal arts school in Winter Park, Florida. She then relocated to Sausalito, California, after landing a job at Access Communications, a Bay Area PR firm. There, she learned the basics, but found the place stifling, with little emphasis on mentorship or relationship building. After hours, though, she hung out with would-be billionaires like Zynga founder Mark Pincus and Netscape cofounder turned venture capitalist Marc Andreessen. "San Francisco in '97 was what I imagine being in Hollywood was like at the beginning of movies," Hammerling says. "Everybody ran in the same circles, so that's how I met them, and it grew. And then I built those relationships."

Then, in 1998, catastrophe struck: Hammerling's mother died of cancer. A few months later, her father died of what she calls "a broken heart." Just 24, she was unmoored. "When my parents died, I went to get money out of my bank account to drive over the Golden Gate Bridge, and I had insufficient funds," Hammerling says. "I'll never forget that day." It was the moment that she decided to quit Access to join a startup. "My parents' deaths made me fearless," she remembers.

When my parents died, I went to get money out of my bank account to drive over the Golden Gate Bridge, and I had insufficient funds.

Not long after, she started dating Mike Mills, bassist for R.E.M., who gave her some inroads to the world of celebrity (it was he who connected her with Bono, who is now a friend). In the wake of the dot-com crash in 2001, Hammerling moved back to New York and leveraged her network to land consulting gigs for big-name clients like Larry Ellison, the billionaire founder of Oracle. Her clientele drew the attention of Zeno Group, a PR firm, which wooed her to join its ranks. But the stint was short-lived. When Hammerling proposed leading a digital-focused "star team" within Zeno, with its own staff and budget, she ran afoul of the firm's old guard. "The woman who ran L.A. said, 'There are no stars in PR. It's the team,' " Hammerling recalls. So she quit on the spot.

That year, Hammerling launched her own shop out of her apartment and named it Brew, after a childhood nickname used by her parents. The timing was fortuitous— Hammerling's was one of the few tech-focused PR firms in New York, a city with a burgeoning startup scene. A year later, she partnered with Dena Cook from Zeno—"We quickly realized we shared the same sentiment about the problems of an agency," says Hammerling. "I don't think Brew would be Brew without her."

Among their top rules: They won't work with communications departments at large companies, liaising only with CEOs and an executive team. Also, no gimmicks. "We don't do party PR," she says flatly. Arguably one of Hammerling's smartest moves has been refusing to solicit new clients, a key aspect of agency life that Hammerling loathed. "We are referral only, and it's amazing when you say, 'No, I'm not going to pitch you,' how many people want you," she adds.

All those years of strategic networking culminated over dinner in 2013, the night before a TED conference, as Hammerling dined with Cameron Diaz over sushi in Long Beach, California. Hammerling invited Bono, who was on the TED lineup, to join them. He brought with him his pal Matthew Freud, the head of British PR firm Freuds. The pair hit it off. "He's passionate about only working with people and businesses that inspire him, not just those who write a check," she says. Two years later, he bought Brew, reportedly for $15 million. "We're still running the show," Hammerling insists. (She and Cook now share a joint board seat on Freuds.) When Freud reminded her that if she left Brew, she would be barred from working for a competitor, Hammerling laughed. "I was like, 'There's nothing else. If I'm not working with Brew, I'll go and sell jewelry on a beach or something.'"—Yael Cohen

Unlike in New York and Los Angeles, where mogul spotting is as easy as snagging a prime lunch table at Michael's or The Polo Bar, San Francisco's elite are a far more low-key group. Good luck identifying tech's masters of the universe amid the hoodie-wearing masses. But in a city known for its warp-speed innovation, even that's changing, fast. and Xochi Birch has a lot to do with that.

Birch and her husband, Michael, preside over The Battery, a private social club for Bay Area ballers. Opened in 2013, it's housed in a 58,000-square-foot former marble factory in downtown San Francisco. It's tricked out with hotel rooms, meeting spaces, a gym, a spa, a restaurant, and four bars. (Dues are $2,400 a year.) The Birches are The Battery's gatekeep- ers, personally overseeing who gets the nod (4,043 so far) and who gets wait-listed. The goal, Birch says, is to draw a diverse clientele, the young and old, artists (well-off ones, at least) as well as CEOs. "San Francisco right now feels like it's at a turning point," Birch says. "When we first came, in 2002, it was a ghost town. It felt like there was nobody out at night, nobody on the streets."

Social clubs have always done well in San Francisco, but none have managed to tap into the Bay Area's newly minted mogul class quite like The Battery. "I've been to the Pacific- Union, and we were the only people in the room for a long time," she says, referring to the stately men's club with an entrance fee in the tens of thousands. "A lot of our members have never been members of a club before. They're even people who don't like the idea of a private club. But they like our vision and concept."

That vision involves shrugging off the crusty airs of traditional clubs in favor of a salon-type feel. There's a robust arts program featuring exhibitions, artist talks, and guided gallery tours; a popular lecture series recently drew a packed house for a tutorial on lock-picking. (The old-fashioned kind.) In 2014, Birch launched Battery Powered, a philanthropic fund that lets members choose "themes" that dictate where their donations will be invested. Already $7.5 million has been raised for charities tied to early education and the California prison system. So successful is the club that Soho House, which competes for the attention of upscale trailblazers, allegedly postponed its plans to open a branch in San Francisco because of The Battery.

San Francisco felt siloed, so we built the club we wanted.

Raised in industrial Pittsburg, California, an hour east of San Francisco, Birch was the eldest of six kids. Her father worked in financial aid for a community college, while her mom worked for Head Start, the federally funded early childhood education program. Birch met her husband, a U.K. native, while studying business administration abroad in London. After they married, they moved to San Francisco and together launched an early social network called Bebo. Both computer programmers, he handled the code while she ran the firm's operations. After years of bootstrapping—and having three kids along the way—they amassed some 45 million users in the U.K., where Bebo was more popular than Myspace. AOL swooped in to purchase the company in 2008 for a staggering $850 million. (AOL, in turn, ran Bebo into the ground, and the Birches have since grabbed it back for a paltry $1 million.)

With the proceeds of that sale, they bought an 11,558-square-foot mansion on the city's august Broadway Street, just a few doors down from Ann and Gordon Getty and Nancy Pelosi, and snapped up a 588-acre vineyard estate in Sonoma. But cracking the city's social strata proved challenging. "When I moved back here from London, I just realized there was a lack of community. I'd ask Michael why we didn't have any friends outside of tech or a neighborhood bar," Birch says. "San Francisco felt siloed, so we built the club we wanted."

When Beyoncé and Jay Z rolled through town in February before her Super Bowl half- time show appearance, the mega-couple hosted a dinner at The Battery, a triumph for the Birches. Not that they've forsaken their tech roots altogether for the glittery new scene they've had a hand in cultivating. The Birches are also relaunching Bebo as a live video-messaging app called Blab—a "pivot" in digital parlance. "People thought it was funny that we bought it back, but it was a good challenge to see what we could do with it," Birch says. "It's all very Silicon Valley, isn't it?"—Lea Goldman

This article appears in the May issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands April 19.