The Sylvia Plath You've Never Heard Of

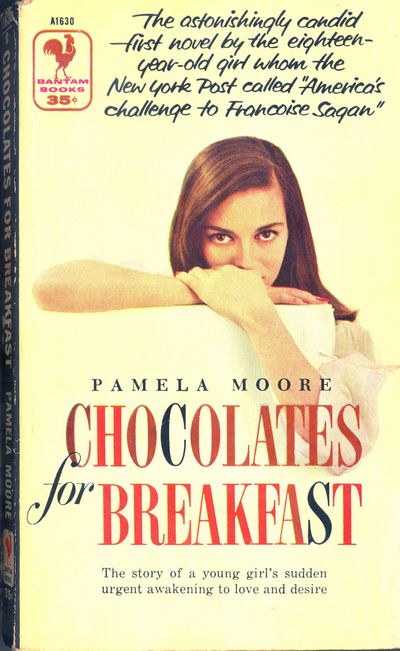

Pamela Moore was 18 when her novel, Chocolates for Breakfast, was published to rave reviews. Then the reviews stopped raving.

Shortly before her 18th birthday, on September 22, 1955, Pamela Moore, then a sophomore at Barnard College, completed the manuscript for a novel called Chocolates for Breakfast. With sexually explicit themes and an underage but savvy protagonist, the storyline would have been transgressive for anyone to write in the 1950s, let alone a teenage girl.

Reviewers agreed. Simultaneously contemplative and frank, the novel earned Moore the compliment of being called "an American Françoise Sagan"—the 18-year-old French author of the sexually-charged bestselling 1954 novel Bonjour Tristesse—by The New York Times. "Not very long ago, it would have been regarded as shocking to find girls in their teens reading the kind of books they're now writing," the review stated. Chocolates would go on to be published in 11 languages and sell over 1 million copies; years later, Courtney Love would say that her mother, taken with the book as a young woman, named her after the protagonist. In 2012, Lena Dunham cited the novel as "required reading," and showed off her worn copy on her Instagram feed. Moore's debut is "glamour and pain and teenaged misery," says novelist Emma Straub, who wrote the foreword for the 2013 American reissue from Harper Perennial. "It's the fucking best."

But despite its praise, Chocolates for Breakfast remains one of contemporary literature's biggest secrets. Out of print for 40 years after its young author's early suicide, the book earned its reputation traveling across generations of women, one vintage paperback at a time.

Moore never took a writing course. As the daughter of two writers, she never needed to—her parents often discussed craft at the dinner table.

Moore's father, Don, who graduated second in his class from Dartmouth University, edited pulp novels and wrote comic strips. In 1934, he married Isabel Walsh, a writer for Redbook and Cosmopolitan. Pamela was born three years later. During the early 1940s, Isabel wrote three pulp novels for Rinehart & Company, the publisher that would one day publish Pamela's work.

After World War II, Moore's parents divorced, and they moved to opposite coasts: her father to Los Angeles, to work as a story editor for Warner Brothers and RKO Pictures, and her mother to New York City to edit Photoplay. Pamela lived, for the most part, with her mother—on Park Avenue just above 86th Street—but traveled to L.A. to spend time with her dad.

Chocolates for Breakfast explores similar terrain: 15-year-old Courtney Farrell is the only child of an East Coast publishing tycoon and a failed Los Angeles actress. Following an unrequited crush on a female teacher, Courtney leaves her posh New England boarding school and relocates to Los Angeles to live with her egocentric mother. Between wandering around the Garden of Allah Hotel and drinking black coffee at drugstore breakfast counters, she navigates an affair with an older man, impromptu cocktail hours with her mother, and a nervous breakdown. Eventually she returns to New York City, where she attends parties with boys from Yale and muses over the ineptitude of her parents, and adults in general.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The book wasn't necessarily autobiographical, she told the Barnard Bulletin, her college newspaper. (Though further similarities can be drawn between her and her protagonist: Moore also attended an exclusive girls' New England boarding school and lived for a period in Los Angeles amidst divorced parents. Her mother, too, was evicted from the Garden of Allah for failure to pay rent, a plotline in the novel.) "No one can teach you to write," she told the Bulletin. "You can be shown how to put your material on the market and you can be taught what kind of stories are in demand. [...] The rest must come from actual experience."

Moore started writing at 14, sketching out ideas and short stories in her diary. In an entry dated 1952, while attending the Rosemary Hall school in Greenwich, Connecticut (now the co-ed Choate Rosemary Hall), Moore seems to know exactly where she's going—or at least where she intends to: "[F. Scott] Fitzgerald has become my number one inspiration...I saw that he had, when a boy, a "ledger," in which he recorded his most personal thoughts + observations... Since I share the same ambition he voiced as a Princeton undergraduate ("I want to be one of the greatest authors that ever lived, don't you?")...I decided a "ledger" might be useful..."

She didn't graduate high school. Instead, after completing 10th grade, she took private tutoring lessons over the summer, passed her college board exams, and entered Barnard one month shy of turning 16. Then, in 1953, Pamela asked her mother to pass along one of her short stories, "The Bad Actor," to her literary agent, Monica McCall. Moore writes in her diary that her mother returned with the following message: Pamela would be better suited to writing novels.

Young Pamela Moore with her mother and father at the Stork Club in New York City.

The seemingly backhanded compliment set Moore in motion. During her sophomore final exams, in the summer of 1955, she began writing Chocolates for Breakfast.

Moore wrote well into the evenings, recalls Barbara Bisco, a former classmate. Bisco first encountered Moore at Rosemary Hall in 1949, when both girls were 12, and formed a fast friendship with the smart, funny, precocious pre-teen. "During the Chocolates days, she didn't talk about her writing with anyone," says the 79-year-old Bisco, author of the novels Night of the Water Spirits and A Taste of Green Tangerines. "She wrote Chocolates late at night after putting in what must have been very full days, painting scenery as an apprentice in a summer stock company."

McCall retained Moore as a client and oversaw the sale of her manuscript, tentatively titled Everything Happens in September. (Family lore alludes to another working title: Dead Leaves in the Swimming Pool, a recurring image in Chocolates for Breakfast.) Rinehart & Company, home to Norman Mailer and Langston Hughes, bought it the following spring, giving Pamela a $1,000 advance. Moore's mother later admitted that she hadn't shown her agent the short story at all; she'd simply wanted to incentivize her to write a novel.

Despite Moore's furious dedication to her future career, she was startled by the sale. In her diary, she writes: "When Monica first told me the novel had sold I still didn't feel I could—had the right to—call myself a writer... I was sitting in my 10 a.m. class, yet in the back of my mind I realized that I was going to Rhinehart that afternoon to sign my contract + have my first editorial conference. Suddenly—at about 10:45—a great fear came over me, as though I were standing on a height. 'I don't want to go,' I thought. 'I don't want to sign my contract, + begin my career, + change my life.'"

"In Europe, she was considered an intellectual spokesman for American youth. In America she was treated as a 'scandalous young girl'—a literary freak who had typed a book at 18."

Three days after the contract was signed, Moore was back to concentrating on her schoolwork and trying to navigate the mixed response from her parents. While Moore describes her father as "proud" of her book deal, her mother's envy was evident: "Mummy may be proud—Monica says she is!—but jealousy obscures this, jealousy + an outsized sense of her own defeat + failure ('I can't live vicariously, you know that'—between tears.)"

Then the author started her junior year. "Fame has come to Barnard," declared the Bulletin story about the publication of Chocolates, with the headline "Eighteen Year Old Writes First Novel." Moore told the Bulletin she planned to continue a double career as a novelist/playwright and as a history teacher (she majored in ancient and medieval history). Meanwhile, her literary prowess intimidated her classmates, like Vivian R. Gruder, also a '57 Barnard alumna and a former debate teammate of Moore's. "As an unworldly young woman from the Bronx myself, I thought that she was a worldly, sophisticated young woman who had much more social and cultural experience than I had," says Gruder, a retired history professor of Queens College. "Of course I was aware of her novel. She talked about it and was quite proud of her accomplishment."

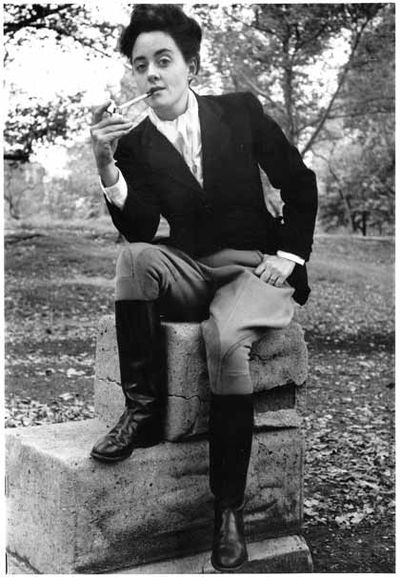

Pamela Moore, 18, before the publication of her debut novel.

A few months prior to Chocolates' publication in 1956, Pamela used her $1,000 advance to finance a solo trip to Europe to continue her Barnard education abroad—a daring feat for an unmarried young woman in the 1950s. While boarding an ocean liner in New York City bound for England, the 18-year-old met Edouard de Laurot, a 34-year-old French avant garde filmmaker, writer, political activist, and World War II hero. Moore was so taken with Laurot that she worked with him to concept her second novel, Prophets Without Honor, while sailing together to Europe. Moore even rearranged her travels so she could get to Paris earlier than she had originally planned, specifically to see Laurot. In a letter to his business partners, Laurot clearly recognizes his influence on her: "She became first interested then engrossed in our ideas and I have little doubt her next book (which we started outlining together) will at least bear visible traces of our encounters."

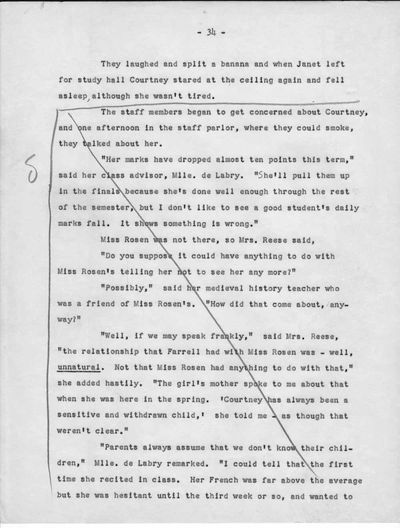

A page of the Chocolates for Breakfast manuscript.

While Pamela was abroad, Chocolates for Breakfast saw its American publication—and a flood of critical praise. (By the next spring, it would have sold between 600,000 and 700,000 paperback copies). Meanwhile she was busy at work amending, already, the second French version with new material. In the preface, Moore addressed these additions as "the unexpurgated version" and says she had unintentionally censored herself in the original American version by being overly conscious of how her intended readership expected to see teenagers depicted. "It is difficult for us to offer each reader the unvarnished truth, especially when it concerns the essential conflict that exists between the principles of our way of life and the demands of the human condition," she writes. "This is what led me to express myself with some reticence in the course of my initial work."

Indeed, Moore's publishers were keen to capitalize on the salacious aspects of Chocolates, marketing the work as a pulpy, sexually explicit dime store read. (In 1964, the New York Post remembered the novel as "sizzling evocations of nymphomania, homosexuality, and other provocative themes.") But Moore's distillation of young female desire is much more complex than that. She renders Courtney both autonomous and performative, freely and consciously trying on the sexuality of others: "As she talked to [Barry Cabot], she thought, I'm going to go on talking to him… I'm going to make him want to stay with me. And she remembered what she heard an actress who had become a symbol through attractiveness to men say to her mother, "When I'm with a man, all I think is sex, sex, sex." She decided that she would try that." Yet Courtney also resists being reduced to her sexuality. When a concerned older neighbor tries to chastise Courtney for taking up with male company, she is quick to redirect the conversation to its double standard: "Al, will you please stop lecturing me?...I'm sick of your moralizing, as though I were a fallen woman or something."

Much the same way Jong's Fear of Flying has forever been branded by its "zipless fuck" despite its deep study of Judaism, family, marriage, and gender roles, Moore's novel suffered similar, limited branding. For a novel packaged as trashy and illicit, Chocolates effectively tackles complex social and cultural issues. Courtney's struggle with depression is meticulously detailed, and layered with substance abuse. After one of her lovers ultimately leaves her for a man, Courtney cuts the insides of her fingers with a razor blade, in perhaps one of the first documentations of cutting in young adult literature: "She took one of the razor blades from the package and held it above her hand..She was too intelligent to hurt herself. But no, she would allow herself the luxury of self-punishment. She would give in."

Moore post-Chocolates for Breakfast success.

As Chocolates for Breakfast continued to sell, the American press was increasingly fascinated with Moore and her personal life, which frustrated her, recalled Milburn Smith, a friend of Moore's and Columbia College undergraduate during Moore's Barnard days. "In Europe, she was considered an intellectual spokesman for American youth," he wrote in the December 1964 issue of men's magazine Jaguar, "while in America she was treated as a 'scandalous young girl,' a literary freak who had typed a book at 18." Moore responded by dodging interviews and limiting contact with family and friends for the next two years—particularly her overbearing mother. Dorothy Kilgallen, a popular gossip columnist and friend of Moore's mother, describes Moore in a 1956 column as a shadowy figure, "in a trench coat and sunglasses, spotted at the back of a café or hurrying through the streets…" All the while, Moore was continuing her studies, completing her final year at Barnard abroad in Europe. She would graduate the following semester, in 1957.

"She was practicing a lot of secrecy," says Moore's son, Kevin Kanarek, who has preserved her legacy on chocolatesforbreakfast.info, "because she got mixed up with Laurot and his projects." Moore sank money from her advance into Laurot's experimental film, Sunday Junction, focused on automobiles and American suburbia. That was only the beginning of her devotion.

Pamela Moore and Edouard de Laurot in Geneva, Switzerland.

As Laurot traveled between Poland and East Germany, Moore would wait for him in various towns along country borders, driving him to Stockholm and Switzerland, and procuring various film equipment when needed. At the same time, in an effort to further escape her mother's grasp, Moore made a drastic career move: She changed literary agents.

"She was feeling that her mother's agent would be passing information on to her mother," Kanarek observes. "So then she went out looking for some young, inexperienced agent she could have more control over." She found one in Sterling Lord, whose other clients included the not-yet-published Jack Kerouac. By 1958, Lord had sold Moore's second novel, Prophets Without Honor, to Knopf based on the estimated 20-page outline she'd created with Laurot—a testament to how popular Moore had become in the United States.

On and off, Moore returned to her mother's New York apartment only to leave for Europe again.

In 1958, while on a stint in the United States, mutual friends in New York City introduced Moore to Adam Kanarek, a Holocaust survivor then working at the Columbia University library. When Moore returned to Europe, the two corresponded platonically about politics, ideology, and religion. Moore shared details about her projects with Laurot, and stories about his heroic past. But Kanarek had a background in U.S. military intelligence and a sharp knowledge of history—he sensed that Laurot had been lying to Moore about serving in the military, among other things.

"He was telling the most insane stories, and then it would turn out that only one of those stories was actually true," Moore's son says of Laurot. "But then he would tell another story that would contradict the first one."

In fact, Laurot had never been who he claimed. According to his passport, he was Polish, not French; his actual name was Edward Lada-Laudanski. In a video obtained by digital archive Web of Stories, Jonas Mekas, co-founder of Laurot's film culture magazine and a collaborator on the film Guns in the Trees, describes Laurot as "a mysterious person with mysterious achievements and credits and past."

Much the same way Jong's Fear of Flying has forever been branded by its "zipless fuck," Moore's novel suffered similar, limited branding.

Moore's relationship with Laurot came to a climactic end when Laurot arranged a meeting with her in New York City. Kanarek arrived in her place and the two men had a terse conversation on a bridge over the FDR Drive in lower Manhattan (a scene later fictionalized in Moore's Prophets Without Honor). In the afterward for the most recent French reissue, Moore's son writes that Laurot and his father had a cinematic stand down: "Kanarek, stalwart and stocky in an ill-fitting suit; Laurot, tall, gaunt and elegant, hissing 'I have people behind me,' before finally backing down."

"I see my father being her loyal friend back in America who then rescues her by proving that Laurot is a charlatan," says Kanarek. The relationship flourished: Moore and Kanarek married in 1958 in a small wedding of only four guests. The couple moved to the East Village, where they lived while Kanarek graduated from Brooklyn Law School and Moore continued working on Prophets Without Honor.

Despite the fact that Knopf had shelled out a $5,000 advance upon reading an outline for her second book, they ultimately rejected the manuscript. The final product had veered considerably from the outline she'd worked on with Laurot, and from the key elements that had made Chocolates such a monumental success. A fictionalized account of her time abroad, meeting Laurot, and finally Kanarek, Prophets Without Honor featured a singular, menacing villain. "It became like a James Bond story," observes Kanarek, who estimates there to be roughly six versions of the manuscript, varying from 250 to 800 pages. Smith recalls the manuscript as "very long, and not especially sexy."

By 1960, a now 23-year-old Moore watched as sales of Chocolates for Breakfast slowed. And, broke from Europe and Laurot, she owed back taxes on at least $25,000 of advance money. She published three more novels: The Exile of Suzy Q, East Side Story (The Pigeons of St. Mark's Place,) and The Horsy Set. But while they all stuck to the Chocolates for Breakfast formula—the burgeoning sexuality of precocious young girls—none achieved the tremendous commercial success or literary acclaim of her first.

Moore\'s author photo for her novel, The Horsy Set.

And once again, Moore found herself—and her work—under the thumb of an intimate partner. Kanarekwas exerting influence.

Bisco, who met with the couple frequently in New York, was concerned about the marriage, particularly Kanarek's effect on Moore's writing. "It was clear that she loved Adam very much, too much in my view," she says. "She allowed him to exert an extraordinary degree of control over all aspects of her life, including her writing. I think that accounts for the differences between Chocolates and her other books." (In press interviews, Moore cites her husband as helping her cope with the disorienting effects of fame.)

Kanarek began working full-time as a lawyer, and in 1963, the couple welcomed their first and only child, Kevin. Moore suffered a difficult labor, followed by a long in-hospital recovery. She resumed writing in their Brooklyn Heights home, now tasked with caring for a newborn in addition to the standard expectations of being a 1960s wife.

While Kevin was still an infant, Moore began working on a novel tentatively called Kathy, about a once-successful female celebrity examining her professional failure. Her sense of self, Kevin stipulates, had started to fade.

On Sunday, June 7, 1964, Moore sat down to write with her nine-month-old son in the next room. Her husband left the apartment around lunchtime to visit his father. When he returned home near 5 p.m., he found her dead on the floor beside her typewriter.

Moore had committed suicide by shooting herself in the mouth with a .22 caliber rifle. She was 26.

A diary entry dated that same day indicated that she had been struggling with the Kathy manuscript. She left an explicit suicide note and police officers at the scene told the press that Kathy contained suicidal themes, with one female character making reference to Ernest Hemingway's suicide by firearms. The next-to-last paragraph of the final page she was working on reportedly described a rifle barrel as "cold and alien" in a character's mouth.

To read Chocolates for Breakfast is to stumble upon a curiously missing piece of the American feminist literary canon.

Shortly before her death, Moore said in an interview, "I lost my identity as a writer by becoming a celebrity." Some suspect that she suffered from bipolar disorder. As Bisco observes, "In retrospect I can see that she was subject to extremes of highs and lows, but I wasn't conscious of it at the time. The highs were clear, but she kept the lows to herself. "

Kathy was never published, and Chocolates fell out of print. By 1970, it was impossible to find a novel by Pamela Moore in the United States or in most of Europe.

But to read Chocolates for Breakfast is to stumble upon a curiously missing piece of the American feminist literary canon. Moore's evocative exploration of sexuality and her meditation on a daughter's role in a dysfunctional household unquestionably place her work in the company of The Bell Jar, Diary of a Mad Housewife, and Fear of Flying. Courtney's position as a sexually active young woman in a culture that doesn't know quite what to do with her feels startlingly modern.

The adults and parents in Chocolates, the supposed linchpins of societal norms, are the most sinisterly drawn of all the characters. Forever handwringing over the wellbeing of Courtney and her friends, they exist as hypocritical foils, incapable of sobriety, of staying married, of fidelity, of the very values they claim to want to instill in their children.

The revival—and sustained readership, through passed-down paperbacks—of Chocolates for Breakfast makes it clear that, culturally, we still don't know what to do with girls like Courtney Farrell. Nor do we have anything new to tell them except discouraging sex and coaxing them into marriage. Chocolates is a reminder that much happens in between.