I Was Taught to Hide My Heritage

Being Chinese-American, I was always plagued by feelings of "less-than"—until I learned why.

"My mommy was Chinese, my daddy was Japanese, and so I turned out like this," a girl in the elementary school cafeteria said, pulling the sides of her eyes into grotesque slits. She and her friend looked at me and giggled, waiting to see my reaction.

I didn't react. Or if I did, I probably laughed along with them. As a child, I grew up mostly in Europe and in white suburbs around the United States, I was the only Asian, and I desperately wanted to fit in. Jokes like these were as common as the greasy cheese pizzas the cafeteria ladies slapped on our plastic trays.

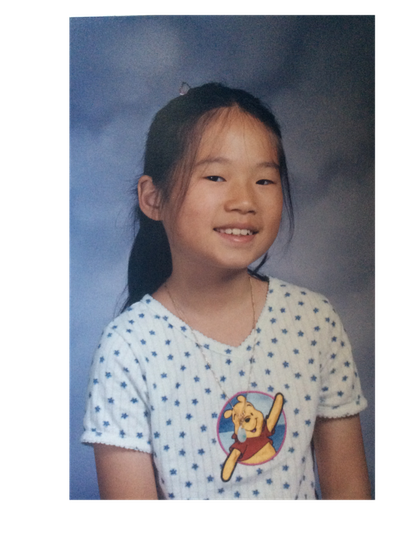

The author in 4th grade.

When kids opened a textbook that had a stock photo of an Asian girl in it, they would ask me if she was my sister. Girls would comment on my "pretty, long, dark hair" that they said reminded them of the "Indian doll" they had at home (two girls even pulled out strands of my hair to keep as souvenirs). I had a math teacher who skipped over my name (Jiaying) during attendance every single day for an entire school year because she didn't know how to pronounce it (this was before my parents anglicized my name to Jenny). I was too embarrassed to raise my hand and tell her I was there.

I didn't know it at the time, but growing up in this environment had a profound effect on my self-esteem and my sense of identity. When we were asked to draw pictures of ourselves in elementary school, I'd draw a girl with curly blonde hair and blue eyes. In the mornings when I was getting ready, I'd stand in front of the bathroom mirror and lift the lids of my eyes to make them seem larger. In high school, my friends and I made sure we differentiated ourselves from the F.O.B. Asians ("fresh-off-the-boat") as if we were somehow more "white" for being raised in the United States. My parents told me that if anyone asked me where I was from (a question I got a lot), I should tell them that I was from America, which only trained me to be more ashamed of my Asian heritage.

"When we were asked to draw pictures of ourselves in elementary school, I'd draw a girl with curly blonde hair and blue eyes."

Neither my parents nor I wanted to think about racism because we were afraid that thinking about it would serve only to sharpen the divide between us and everyone else. It wasn't until I got to college that I was challenged to think about how racism really impacted me. I went to a very white liberal arts school in Maine—probably an extension of my desire to be white. Ironically, as one of the few people of color on campus, I was called on to lead discussions on race—discussions I had never been a part of before. Through those (often uncomfortable) conversations, anthropology classes, and readings, I started to understand how insidiously racism flows through the daily fabric of our lives.

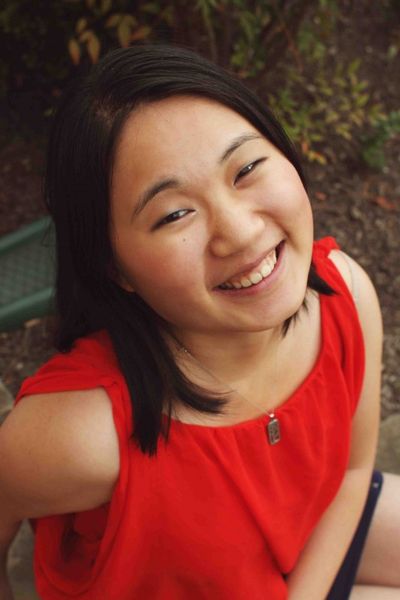

The author today.

I began recognizing that my need to constantly play up my country of birth (Germany) and downplay the country of my parents' birth (China) was a product of racism.

I learned that when our old neighbors called my parents Communists, they were being racist. The girls who pulled my hair, the kids who joked in the cafeteria–they were all playing out a disturbing system of oppression where the dominant culture asserts itself as better than anything that is different.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

I came to understand that my feelings of inadequacies and shame were actually manufactured from this system of oppression.

Having that knowledge now has allowed me to become more comfortable with my racial identity. I am comfortable claiming my Chinese heritage without feeling like I have to defend my American-ness. I don't have to accept all the labels of "less-than" that the racism I grew up with would have me believe.

A few months ago, I brought my car into the MVA for a vehicle emissions test. The young guy who was running the test chatted and flirted with me a bit. He asked me where my parents were from, and I told him they were Chinese. The question used to annoy me because I didn't want people to point out that I was different, but I've since developed enough pride in my parents' heritage that I'm willing to humor the occasional ignoramus. After the test was complete and I climbed back in my car, he asked me my name.

"Jenny," I said.

"Jenny?" he said with a confused look on his face. "That's not a Chinese name."

"That's because I'm Chinese-American," I said as I closed my door. "There is such a thing, you know."

Follow Marie Claire on Instagram for the latest celeb news, pretty pics, funny stuff, and an insider POV.

Jenny J. Chen is an award-winning science journalist and multimedia producer. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, NYTimes.com, NPR, Washington Post, Reader’s Digest, Vice, and many more. In 2014 and 2015, she was awarded a PRX STEM grant to produce stories for NPR member stations across the country. In 2014, she received a grant from the D.C. Humanities Council to produce a radio documentary series on growing up mixed race in Washington, D.C. Jenny has also received numerous fellowships and awards to cover health, aging, minority issues, and climate change. She has spoken about journalism and the role of ethnic media at the Smithsonian Folklife festival. In another life, she has also had a play produced at Arena Stage and the Kennedy Center.