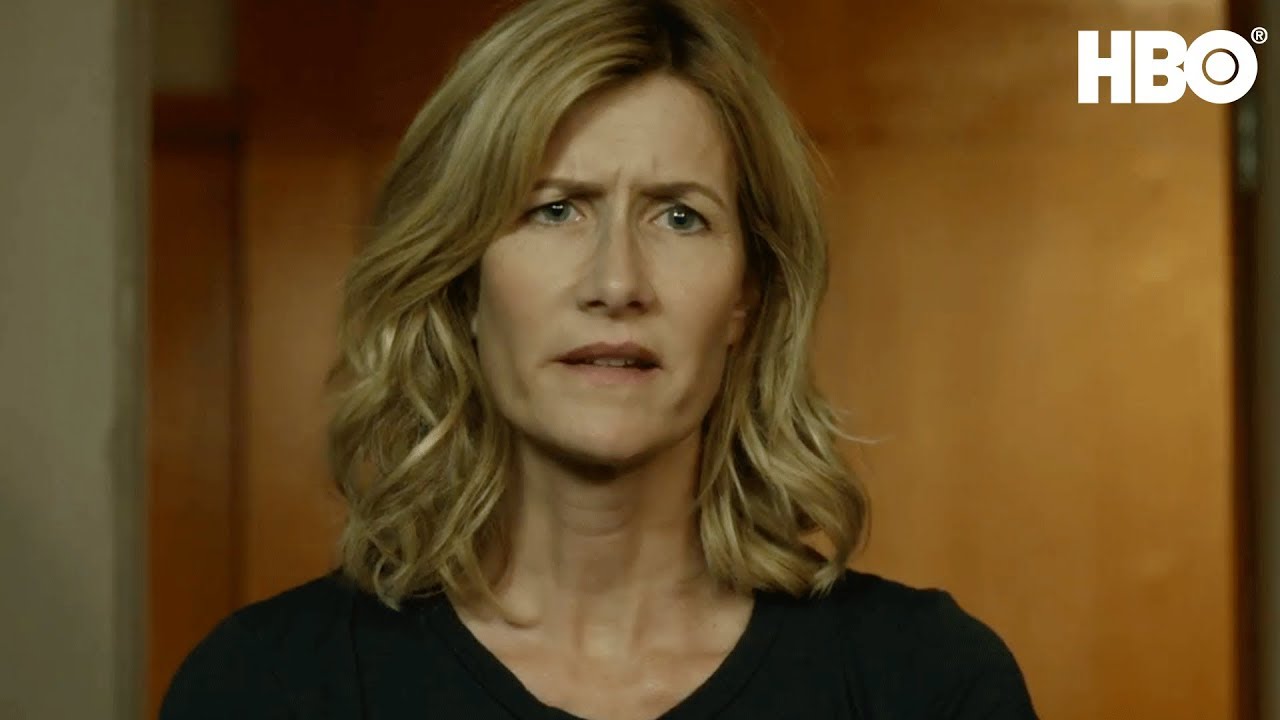

This Woman's True Story of Child Sexual Abuse Is Now a Movie Starring Laura Dern

Writer-director Jennifer Fox on confronting her murky past for her new autobiographical HBO Film, The Tale.

Jennifer Fox was 13 years old when her running coach—a man nearly three decades older than her—lured her into bed. As a child, Fox didn’t see his behavior as predatory or abusive. Rather, she thought of him as her first boyfriend, her first love. She held onto this romantic notion for many years, until, as an adult in her forties, she began sifting through her memories and realizing something much darker had occurred.

Fox, an acclaimed documentarian, tells her life story in a searing new feature film she wrote and directed, The Tale, which will premiere on HBO on May 26, after receiving rave reviews at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year. She decided to make the film, she says, because she was interested in the complexities of memory and “the power of the mind to tell itself the stories it needs to hear to survive.”

Her mining of her own memory began when her mother found a story that Fox had written in middle school—a fictionalized version of her relationship with her coach. Her mom recognized the story as a tale of abuse. Fox dismissed this idea at first, holding onto the memory of a romance. Then she began revisiting her childhood.

The movie unfolds like a mystery, as Fox, played by Laura Dern, tracks down people from her past and confronts her younger self. Fox uses her real name in the film, but has changed the others. She spoke with MarieClaire.com about sharing such a personal story onscreen, the intricacies of scenes depicting sex with a child, and why she decided not to name her abuser.

Marie Claire: It would’ve been possible to make this film without revealing that it was based on your life—what made you decide to tell the world that it happened to you?

Jennifer Fox: It was really practical for me in the sense that I felt if I didn’t leave my real name in it, many audiences might question if it was even possible that a young girl could love a person who abuses them. I felt like I had to leave my name there so that audiences had a face that they could reference, and reviewers would have to talk to me if they had doubts.

Marie Claire: As you started revisiting your past and realizing that the experience was something different than you recalled, was it hard to come to grips with that?

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

JF: I think it’s very hard to admit that someone betrayed you to the degree that child sexual abuse is betrayal. That’s what grooming is: The adult befriends a child, makes them feel special, makes them feel loved. When the lines get crossed into sexuality, first of all it’s very hard to know what’s going on. In my case, I was so naive, I’d never even been kissed by a boy. The adult has built up your trust. And you also don’t want to lose that specialness. So it’s very hard to look at it now in the cold light of being an adult and say, “This was planned. This was manipulation. This was a setup.” It’s painful. It’s definitely painful.

Marie Claire: When you wrote the childhood story that your mother found so many years later, how much detail did it reveal about what happened to you?

Laura Dern stars as Fox in the film.

JF: I handed it in as fiction to my seventh-grade English teacher, but it was coded; it starts at the beginning of meeting [the coach] and goes all the way through breaking up with [him] and why. It’s not graphic, but it’s suggestive. It was 1973, and frankly, people just really weren’t looking for sexual abuse in the way they are today. The teacher wrote on the back, “If this is true, it’s a travesty, but since you’re so well adjusted, it can’t be true.” So it’s not that she didn’t get it, it’s that she just thought it was some kind of fantasy that I’d created.

People have asked me recently, “Do you think it was a cry for help?” It really didn’t feel like a cry for help. What it really felt like was me trying to piece it together and make sense of it in artistic form, like I’ve gone on to do with everything in life. That’s what being a filmmaker is. It was my attempt to make sense of something that was really confusing me. I was pretty aware that the adult world would not know what to do with this information, and so I just—not buried it away—but kept it to myself as my own private story.

Marie Claire: Did you think about the relationship over the years?

JF: Yes, I never forgot it. If somebody said to me, “Who was your first boyfriend?” I’d say, “I had an older relationship when I was 13. I had sex when I was 13.” It was not a hidden memory. It was a memory that I remembered quite well, and quite graphically. The physical scenes in the film are straight from my memory. Even what he says to her is verbatim what I remember. At the time, I just felt like it was something I did that was part of growing up, part of becoming an adult. I was really anxious, like many adolescents, to be taken seriously. I was anxious not to be a kid anymore and to escape being controlled by my parents. The fact that there was pain was just, to me, part of the admission to adulthood. I got something from it: I felt special. I felt like I was a hero—I broke up with him. I did feel special among my peers. I used it to say to my peers, “I’m more mature than you.”

Laura Dern as an adult Fox, talking with the younger version of herself played by Isabelle Nélisse.

Marie Claire: Kids and adults do see things from such different perspectives…

JF: Yes, I have a girlfriend from back then, and we were talking about what happened when I wrote the script. She said, “I remember being in your bedroom when we were like 14, and you said, ‘I had a boyfriend, but I split up with him.’” She was like, “What?” I said, “He was older than me.” My girlfriend, she was just gorgeous, very developed, and I was this skinny string bean. Prior to this conversation, she said, she felt so mature and more developed than me because she had kissed boys. Afterward, she said, her esteem of me rose exponentially because I actually had more experience than her. As adults, we don’t see how kids use these things as well: I used it to stop being a dork that everybody thought I was.

Marie Claire: In the film, the older and younger versions of yourself talk to each other directly, and often clash.

JF: It’s a funny thing, we look back with adult eyes—the film is much about that. As an adult, I’m asking my young self, How could you have done that? I don’t understand that my 13-year-old self went ahead with this. But that’s because I’ve now passed over; I’m no longer the same person I was at 13. If that young person met me today, I would be the enemy because I wouldn’t understand her need to grow up. The film was a lot about acknowledging the voice of the prepubescent girl, letting my child self speak and showing things from her point of view. We need to acknowledge the power of that young person. What I didn’t have—what young people don’t have—is experience. By not having experience, you can’t see a predator that you would as an adult. But the thing that you do have is a point of view; you have thoughts, you’re making decisions, you have agency. It’s just that sometimes your agency is usurped by people you should be protected by.

What we don’t want to collapse is the power of that young girl’s voice. We want to to acknowledge it and allow it to thrive because that young girl is what made me, me. It’s her strength that made me an independent woman, that made me a filmmaker, that made me unafraid to travel around the world. It’s because that voice in me stayed strong that I’m able to do the work I do. I think too often, as adults, we squash that voice. We say that voice is unimportant. But really it’s an independent voice that young girls often have and that we want to encourage. We just want to protect them from predators.

Jason Ritter as the predator and Isabelle Nélisse as an adolescent Fox.

Marie Claire: What made you decide to include scenes showing an older man, played by Jason Ritter, having sex with a 13-year-old girl?

JF: From the beginning—it was a dealbreaker for me—if I was going to make this film, it had to include physical scenes. At first it was just a gut feeling. But if I want to back away from that gut, it’s really the fact that child sexual abuse is a taboo subject. We always look away. By looking away, it kind of goes into some vague soft focus. I wanted to make sure the viewer had to see that this was not a pleasurable experience for me as a child, that this was something painful, that this was not something desired, that this was something that every time it happened, I vomited. That the perpetrator was so narcissistic, he didn’t even acknowledge that. For me, the film is really about: You cannot look away anymore. We have to look at this in all its horror to really understand it and stop it. I have had many people—people who work in the field of child sex abuse—say to me that until they watched The Tale, they didn’t really understand.

Marie Claire: How did you approach the complexities of the role with the young actress who played you, Isabelle Nélisse?

JF: Her mom gave her the script, and she read it herself. And then she asked me all these questions about what happened to me, how it happened, why it happened. Then she talked to her mom and told her, “Yes, I really want to do this because I think it could help other girls.”

There is no physical contact between Jason and Isabelle in the film—it’s all the illusion of filmmaking. The [sex] scenes were actually shot separately. Jason is working with a body double. Isabelle is on a vertical bed, standing up, with her hair kind of glued outward, as if it were splayed on a pillow. And I’m just right in front of her saying, “Act like a bee stung you. Act like your grandmother’s chasing you.” I would roll through these very nonsexual cues. Meanwhile there was a therapist on set. There was a Screen Actor’s Guild representative on set. There was Isabelle’s mom. There were like 20 producers, and we’re all on microphone so everybody hears exactly what I’m saying, and they’re watching it as well. So there’s a lot of control and taking care of her. And even though she knew what the scene was about, she’s not acting that scene ever.

Marie Claire: I imagine it was tough on Jason Ritter to play such a disturbing role.

JF: Yes, Jason does such a gorgeous job in the role, particularly because he embodies the guy who you would trust, the man next door, the good guy. We really wanted to cast a man that wasn’t the way the media would like to portray it—here’s this nefarious, dark, evil guy who everyone can spot from a hundred yards. Jason’s the opposite of that. He just brings so much complexity to the role of the perpetrator and allows us to realize, these men are part of your community. I think it was very hard for him. There were moments when he’d just say, “Give me a minute.” And he’d walk off [set] and cry and then come back.

Jason Ritter and Elizabeth Debicki play the masterminds of the manipulation; Fox changed their names for the film.

Marie Claire: You haven’t publicly identified the man who preyed upon you as a child. Why did you choose not to reveal his name?

JF: Everybody’s different: Some people want to prosecute, some people want to out people, some people don’t. My goal at this point in our lives is not actually to out him. He’s an old man now, near death probably. My real goal was to open the conversation and to have people understand how complex and nuanced child sexual abuse is. That’s my goal, and since I’m the artist, I get to do that. My mother’s goal would be totally different. She would love to see him go to jail. Frankly, the statute of limitations has way run out, so I’m not even able to prosecute him. It wasn’t my goal, though.

Marie Claire: Your mother—played by Ellen Burstyn in the film—had such a crucial role in urging you to reexamine your past. How did your mom feel about your making the film?

JF: We both thought of doing the film, but she was really like, “You have to make a film and you have to make it now.” She was pushing me like crazy. I think she felt like, if Jennifer doesn’t want to prosecute, then let’s use her talents to help other people, and in the process, Jennifer will have to face what I want her to face, which is what happened to her. I started to write this script in 2008 while I was working on other projects. My mom kept calling me up and saying, “Look, time is passing. You have to make this film. You have to get on with it.” She was a big, big force in the project. We started to develop it around 2014.

Marie Claire: That was before the #MeToo movement. To have the film come out now—how do you feel about the timing of it?

JF: I’m thrilled with the timing. I think because of the #MeToo movement and Time’s Up, people’s minds have cracked open and they realize that these things happen all the time. What is new, I think, about the film is it addresses an area that the #MeToo movement and Time’s Up haven’t addressed yet, which is child sexual abuse. And I think that now we can enter another taboo, into the realm of what happens to young children. Child sexual abuse is very complex and nuanced and messy. It doesn’t fit into these black-and-white boxes that the media would like to portray it. By thinking of it that way, we miss the cues all the time.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

RELATED STORY

Abigail Pesta is an award-winning investigative journalist who writes for major publications around the world. She is the author of The Girls: An All-American Town, a Predatory Doctor, and the Untold Story of the Gymnasts Who Brought Him Down.