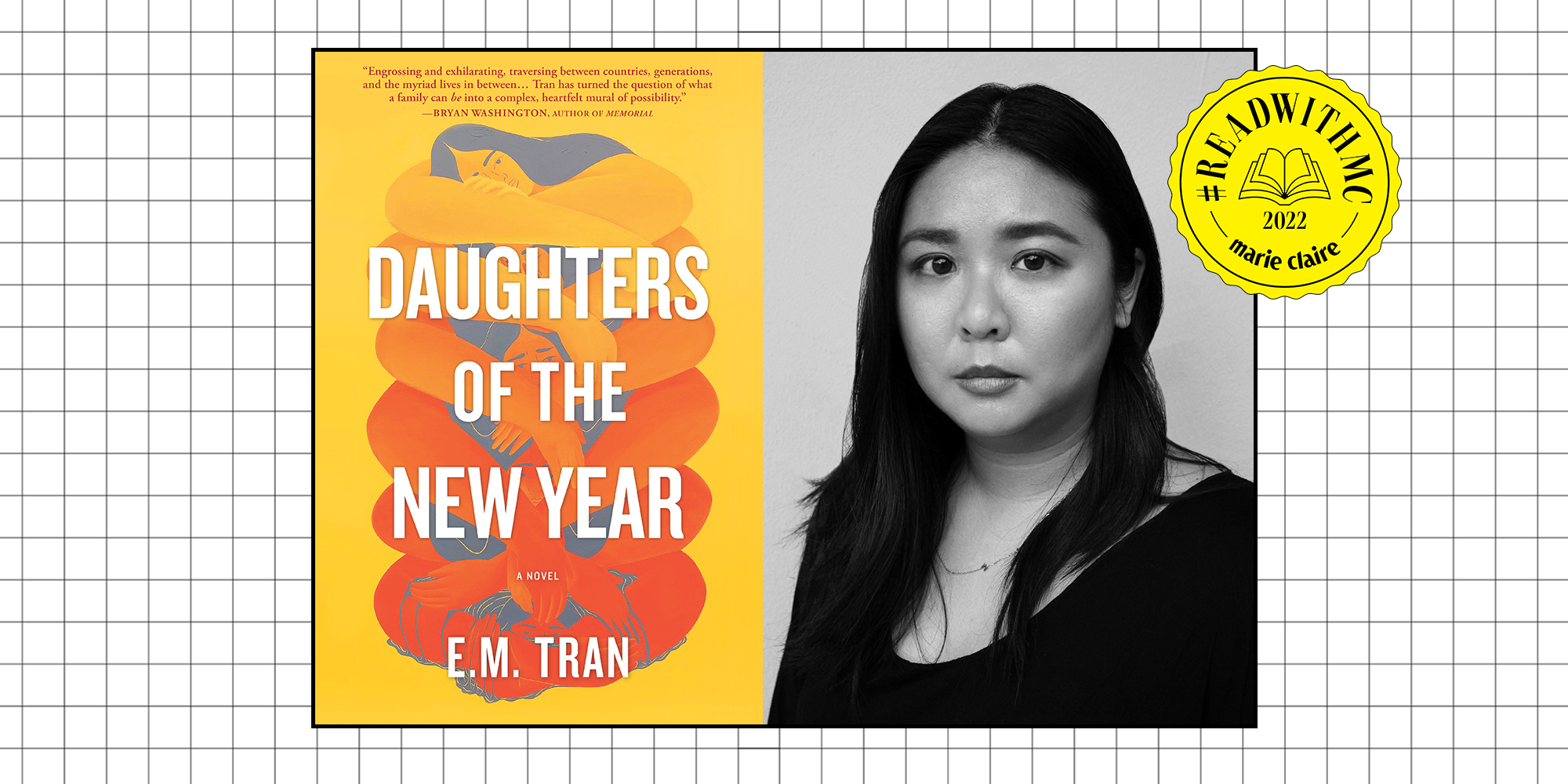

'Daughters of the New Year' Is Our November Book Club Pick

Read an excerpt of E.M. Tran's debut novel, here, then dive in with us throughout the month.

Welcome to #ReadWithMC—Marie Claire's virtual book club. It's nice to have you! In November, we're reading E.M. Tran's Daughters of the New Year, a debut novel illuminating a family's entire lineage and the ancient legend that binds them all together. Read an excerpt from the book below, then find out how to participate. (You really don't have to leave your couch!)

The night before the first day of Lunar New Year, Xuan called her children to give them their horoscopes. She did this every year: for at least a week, she pored over the gigantic book with each sign’s annual predictions and star positions, and the daily zodiac calendar with its moon phases, both of which she bought at the Vietnamese bookstore across town at the strip mall in New Orleans East.

Xuan always called her children in the same sequence: first Trac, the oldest, then Nhi, the middle child, and finally Trieu, her youngest. Every year, she had a private laugh about calling them in their birth order because it reminded her of the zodiac origin story. Her own mother used to recite it every Têt when they lived in Vietnam. Myth had it that the Jade Emperor beckoned all the animals to participate in a race. It was an invitation to be inducted into the zodiac for all of time, but there would only be twelve victors. The order in which they each crossed the finish line was the order in which they would be immortalized into the zodiac. But, of course, the race was treacherous, requiring the animals to cross every kind of terrain in every kind of weather predicament. The final and most difficult hurdle was traversing the Mighty River, to enter heaven, where the Jade Emperor awaited their arrival.

In the private joke she had with herself, Xuan was the Jade Emperor, and her own children the scrappy animals fighting and clawing their way to heaven to be first, second, and third in the zodiac. Of course, Trac, Nhi, and Trieu cared little about this myth and never noticed that Xuan got a kick out of it. No doubt, they would be annoyed, as they inexplicably were, about anything and everything Xuan did. Xuan had been at Trac’s house just a few days ago, only because Trac had insisted she come for dinner. Xuan didn’t want her children to cook for her. They didn’t know how to cook, not any of them, despite Xuan’s insistence all their lives that they learn.

“I’ll teach you to make wonton soup,” she’d say to one or another of them. Sometimes it was wonton, sometimes it was glass noodles, sometimes it was beef stir-fry. It didn’t matter, because they all responded with traded eye rolls and vague avoidances. “Your mom know how to make the best soup in town. She the best cook in the world,” she’d say, and still, none of them would seem keen to take her up on the offer.

Yet, she had been pressured to come to Trac’s house, which was in a part of town where Xuan hated driving, and was expected to behave politely about her eldest daughter’s cooking. Where she’d learned this cooking, Xuan had no idea. The internet, she was sure, some website for Americans. This was why Trac wasn’t married—what man would marry her when she couldn’t cook a decent meal? And then, and this was the worst part, when Xuan offered help, Trac replied, “I know how to do it,” followed by “God,” disguised under a sigh, as if she was deaf. There was that annoyance again—it cropped up in unexpected moments. She could never manage to prepare herself. It was a kick in the gut. Her children never seemed to notice, always wrapped up in their own defensiveness.

“Are you sure you want to add the pork so early?” she asked Trac.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

“Yes, I want to add the pork this early,” she said. And when dinner was ready, Xuan thought the pork was tough, dry, and too salty.

She wanted to tell her children the directions they should each go for good luck on the first day of Lunar New Year. She wanted to tell them to avoid risky ventures and the color white. She wanted to tell them the recipe for stuffed bitter melon soup. She wanted them to listen, but she knew they wouldn’t. She told them anyway. She told Trac while choking down tough, dry, too-salty pork; she told her youngest, Trieu, while she sat, unresponsive, at the computer; and she even told Nhi, who was in Vietnam filming that horrible reality show about American women fighting over a mediocre American man. She had been mostly out of reach for three months shooting Eligible Bachelor, and must now be nearing the end of the process.

“I don’t think you’re allowed to call her in Vietnam, Mom,” said Trieu, who was currently living in her old bedroom in Xuan’s house.

“Why not? I call her, I’m her mother.”

“You haven’t spoken to her in months.”

“I don’t need reason. I call my child whenever I feel.”

“She’s filming the TV show. I don’t think she has her cell phone.”

“How you talk to her, then?” Xuan asked, and felt a twinge of satisfaction at Trieu’s guilty expression. She’d heard her daughter talking on the phone in her bedroom, speaking so loudly, she was surprised Trieu thought the simple fact of the door being shut was enough to muffle the conversation.

“She only calls me when she has a chance. It’s always from a different phone number.”

“You tell me how to call her,” said Xuan.

Trieu gave Xuan the phone number for Nhi’s agent in Los Angeles. “It’s just some woman in LA. I don’t think you should call her. What are you even calling her for?”

Xuan went into her room with the cordless phone. When the woman picked up, she didn’t say hello. Her voice had a fried, dry quality to it, which reminded Xuan of Trac’s pork.

“Angela Weiser,” she said.

“Hello, this Xuan Trung. I am Nhi Trung’s mother.”

“Oh—hello, what can I do for you?” Brisk and already aggravated, Angela Weiser was apparently not accustomed to unannounced callers.

“I want to speak to my daughter, but I have no way to contact. Do you have the number I can call?”

“Is there something wrong? A family emergency?” The sharp edges of her words had dissolved. Her greeting had begun so efficiently, but now Xuan could hear the core of her.

She was happy that Angela Weiser was her daughter’s agent, whatever that was.

“No, there is no emergency, I just need to speak with her about something.”

“I’m so sorry, Mrs. Trung, but we’re not allowed to contact the contestants. She has designated phone call time, and she only checks in with me every once in a while. I can tell her to call you when we next talk?”

"She wanted to tell them to avoid risky ventures and the color white. She wanted to tell them the recipe for stuffed bitter melon soup. She wanted them to listen, but she knew they wouldn’t."

“I can leave message with you, and you can tell my daughter, okay?”

“Sure,” said Angela Weiser.

“Do you have a pencil? Do you write it down?”

“Yes, I have paper and a pen.”

“Tell my daughter that it will be Year of the Monkey, a very bad pairing for a Fire Tiger like her.”

“I’m sorry?”

“It will be Year of the Monkey,” Xuan repeated. “Tiger and Monkey never get along. They always bicker and fight, so this may be a bad year for my daughter. They have very clashing personality and cannot agree on anything. She may see a lot of conflict this year.” Xuan could hear the pen scratching the paper.

“Is that all?”

“No, she also has to be careful, because the Monkey can be a tricky animal. She should watch out for small tricks or deceit.”

“Small tricks…or…deceit,” she mumbled. “Okay, got it.”

“Also, if you wish for luck in money go to the south direction. If you wish for luck, fame, prestige, go to the southwest. Maybe she should do this because she actress, no?”

“Mm-hmm, I think you might be right about that,” said Angela. “Should she go southwest on a walk, or does it not matter?”

“Yes. First thing in the morning. If you wish all kind of luck, go to the east or west. Overall, east, west, south, southeast, southwest—lucky star move to these direction.”

“So, don’t go north, northeast, or northwest?” said Angela.

“Yes, that right. You should also do this for luck. Only for the first day of Lunar New Year, though.”

“There’s more than one day?”

“Yes. Tuesday the second day of New Year. If you wish luck in money, go to the east. If you wish for all the good news go to the southwest.”

“Wow, okay, so—”

“Wednesday the third day of the New Year. If you wish for all the good news, go to the south. If you wish for a mentor, go to the east.”

“Is that the last day of Lunar New Year?”

“Yes, only three day. You tell my daughter that, okay? If she can, she should celebrate in Vietnam with the correct food. She should not work on New Year, it bad luck. Please tell my daughter that for me, okay?”

“I’ll tell your daughter,” said Xuan’s daughter’s agent in Los Angeles. When she hung up the phone, Xuan went to find Trieu and tell her what Year of the Fire Monkey had in store for an Earth Dragon.

Excerpted from Daughters of the New Year by E.M. Tran. Copyright © 2022 by E.M. Tran. Published by Hanover Square Press/HarperCollins. By arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A., a division of HarperCollins.

Brooke Knappenberger is the Associate Commerce Editor at Marie Claire, where she specializes in crafting shopping stories—from sales content to buying guides that span every vertical on the site. She also oversees holiday coverage with an emphasis on gifting guides as well as Power Pick, our monthly column on the items that power the lives of MC’s editors. She also tackled shopping content as Marie Claire's Editorial Fellow prior to her role as Associate Commerce Editor.

She has over three years of experience writing on fashion, beauty, and entertainment and her work has appeared on Looper, NickiSwift, The Sun US, and Vox Magazine of Columbia, Missouri. Brooke obtained her Bachelor's Degree in Journalism from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism with an emphasis on Magazine Editing and has a minor in Textile and Apparel Management.