Sometimes I Exploit My Sexuality and I'm Not Sorry

We live in a sexist world where sexiness can be an asset, and it's fine for women to wield it to get what they want.

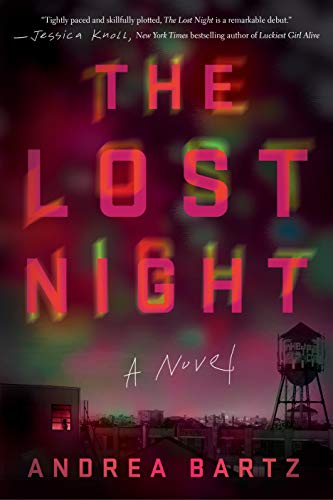

In my new book The Lost Night there’s a throwaway moment that should feel familiar to female readers (even as male ones might miss it). Our heroine, Lindsay, is determined to uncover the dark secrets surrounding her best friend’s apparent suicide a decade earlier, and so she’s making an unannounced visit to the office of her late friend’s ex. Like me, Lindsay’s a journalist, analytical and bright, and she approaches situations the way I would. So when I wrote the scene, I made her take all the preemptive steps that would flit through my own my mind, though we only hear about them in passing: She “clacks over” to the front desk (presumably in heels), smiles wide at the cute young man there, leans on his desk as they banter, giggles “like he’d said something wickedly clever,” and, when he seems amenable to flirtation, silently muses, “Thank god I’d thought to apply lipstick on the subway.”

Though it’s far from her defining characteristic, leveraging her looks is something Lindsay does throughout the novel as she maneuvers her way toward the truth: She strategically employs pretty tears and a bashful stance, or a careful palm pressed onto a man’s arm, or a bright blinky smile evoking a damsel in need of saving. My main character uses her femininity to her advantage, and plenty of smart women (myself included, hi) do the same...and we needn’t apologize for it. We live in a sexist world where sexiness can be an asset, and we shouldn’t feel bad for wielding it to get what we want.

Research going back more than 30 years backs up the idea that being attractive makes life easier. Good looks help you make more money, nab a higher-earning, better-looking spouse, and even score a better deal on a mortgage. Is this fair? No. But it’s reality. We like attractive people, and women—who’ve been socialized since childhood via millions of micro experiences to believe their looks are of tantamount importance—would be remiss not to play off their prettiness.

While sexiness hasn’t been researched the way straight-up attractiveness has, it’s not hard to think of examples of women cashing in on their sex appeal. Kim Kardashian, She Who Broketh the Internet, has made an entire career out of it. Pop culture is studded with portrayals of the phenomenon: Witness Gone Girl’s Amy smoothly talk her way into the relative safety of her estranged ex’s home. Or Breaking Bad’s Skyler White shooing away a suspicious auditor from the IRS with a low-cut top and a blinky dumb-blonde shtick. Or Mr. Robot’s Darlene Alderson going all femme fatale, seducing a (female) FBI agent in order to steal important documents. Such moments are often discussed with heavy judgment, women using their sex appeal to “trick” others (who apparently have no agency or self-control?) into doing their bidding. But maybe these women aren’t evil vixens or cold-hearted harpies. Maybe they’re just, you know, resourceful.

Maybe these women aren’t evil vixens or cold-hearted harpies. Maybe they’re just resourceful.

I am not, of course, advocating for putting on a fake-lust routine and worming your way into your an FBI agent’s bed in the service of stealing from her. But female sexuality is a powerful asset—why not use it? I once had a boss, a C-suite dude in his 60s to whom I had to present my team’s work. Did I change into heels and apply lipstick before every meeting? You bet I did. (And I could tell you it was to feel like my most put-together self, but c’mon, we’re all adults here.) I slayed in those meetings, confidently and professionally discussing what we’d put together and why. I didn’t bear cleavage or find reasons to seductively bend over and grab something off the floor, but I knew I looked good, and I also knew that would make him more receptive to what I had to say.

A friend recounted that once, before she went in for a job interview, someone she knew at the company told her to wear a tight dress. “So I did,” she recalls. “Did I feel bad? Nope! I got the job. Whether it was on my merits or my sexuality didn’t matter to me because I knew once I was in there I would kill it.”

I put on makeup and a cute outfit whenever I know I’ll be pleading a case: asking for a refund, leading a meeting, sitting down with a journalist who’ll be writing about my book. That doesn’t make me antifeminist; it makes me smart. Why would I handicap myself by suppressing my own sexuality?

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

“But you’re objectifying yourself!” I can hear the outrage from here, and with it, the implication that I can’t expect to be taken seriously if I’m also brandishing a bodycon dress and smoky eyes. This gets at a major misconception about female sexuality: People mistakenly think the line between being objectified and empowered is in the eye of the beholder. But it’s actually in the eye of the, er, possessor: Whether you’re being objectified or empowered is your call. Everyday Feminism has an amazing comic walking us through this (drawn by Ronnie Ritchie); the entire thing is worth a read, but in short, the litmus test for sexual empowerment is: Does the person we’re deeming empowered or objectified have the power?

The litmus test for sexual empowerment is: Who has the power?

Take my fictional heroine, Lindsay. When she slicks on lipstick and steps into heels in anticipation of infiltrating this dude’s office, she has the power. When I make myself cute for a meeting or post a hot Instagram of me wearing a bikini or a low-cut top, I feel sexually empowered, not objectified, because I chose to present myself that way.

In our complex and patriarchal society, of course, things are rarely that black and white. A revolting comment from a troll can make me feel less badass and more, well, bad. The horrific norms surrounding rape culture—where looking or acting sexy means you’re “asking for it” and rejecting a man can literally get you killed—can tip the seesaw of power away from you in a millisecond. (I’ve written about this very phenomenon for Marie Claire.) While it is never our job to prevent men from harassing or assaulting us, I know that you—like my fictional Lindsay, like me—are constantly running threat assessments, wondering if, for example, the comfort of running in just a sports bra is worth the inevitable catcalling.

And that’s why I know you’re smart enough to turn this bullshit on its head and twist it to your own advantage. We live in a man’s world, unfortunately, and maybe things are changing (although the backlash to the recent Gillette commercial proves we have a long way to go). But until things actually have—until we live in an egalitarian society where women are taken seriously regardless of our looks and we can walk around in yoga pants without unsolicited comments about what men would like to do to us (and/or, if we push back, how fat we look in said yoga pants and how unf*ckable we truly are)—we shouldn’t hesitate to work the rigged system to our own benefit.

As long as it makes you feel powerful, post that hot selfie. Wear the tight dress. Fight for your slice of the discriminatory, rigged, problematic pie. Milk this messed-up system for all it’s worth, and then use every shred of the power and agency and control you gain to tear down the sexist scaffolding from the inside so that a few decades from now, lipstick and crop tops won’t be weapons in the war against patriarchy—they’ll just be cute stuff you can wear whenever the hell you want.

For more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.

Andi Bartz's debut thriller THE LOST NIGHT received starred reviews from Library Journal and Booklist and was optioned for TV by Mila Kunis and Cartel Entertainment. Her second novel, THE HERD, was named a best book of 2020 by Real Simple, Marie Claire, Good Housekeeping, and CrimeReads. Her third thriller, WE WERE NEVER HERE, was a Reese’s Book Club pick and an instant New York Times bestseller; it’s in development at Netflix. Her fourth book, THE SPARE ROOM, was a GMA Bonus Buzz Pick, a Marie Claire book club pick, and a best book of summer per People, Shondaland, Glamour, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, and more.

Bartz's most recent thriller, THE LAST FERRY OUT, has been praised by ELLE, Marie Claire, Cosmopolitan, and more. She also publishes the Substack Get It Write.