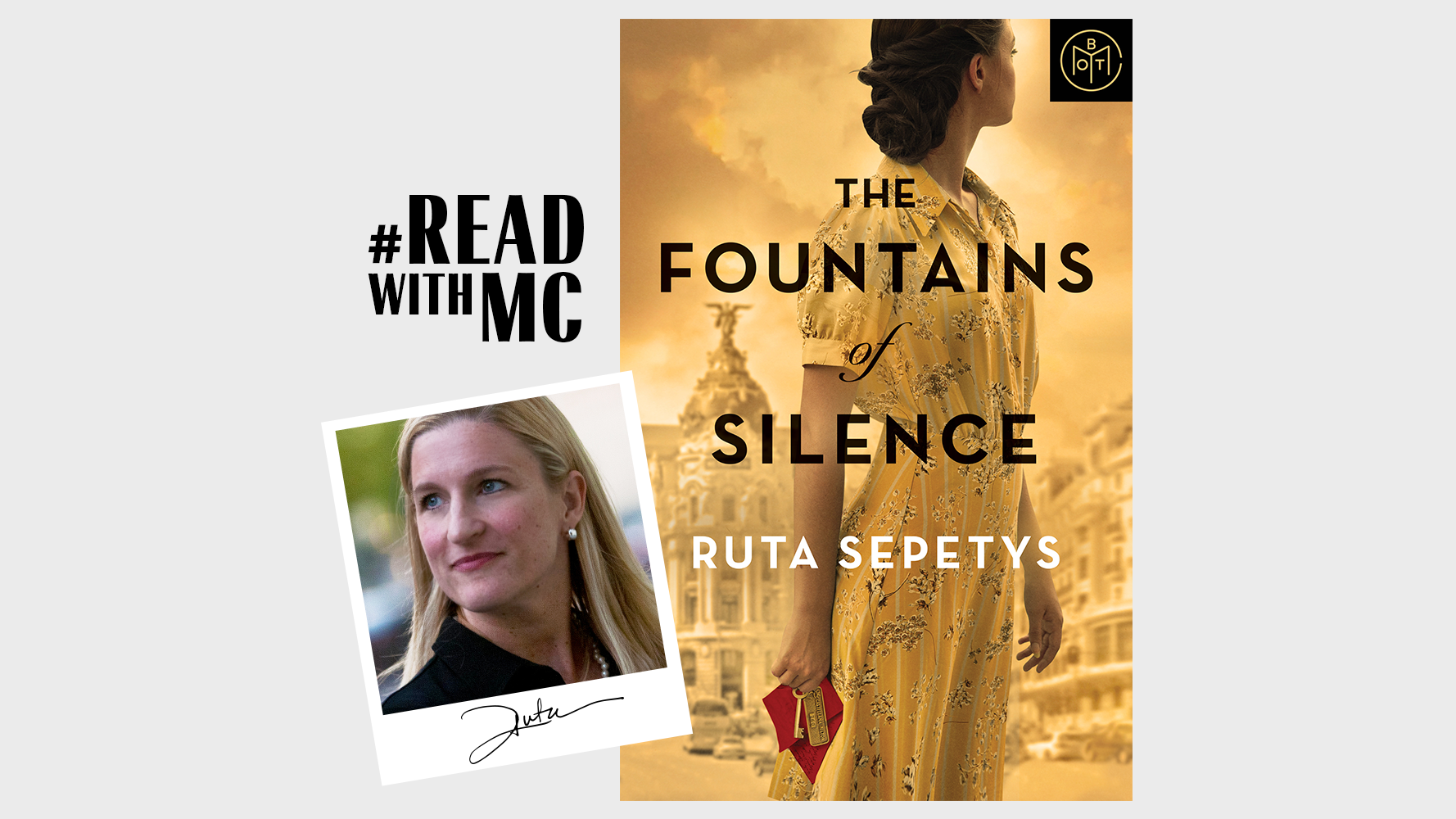

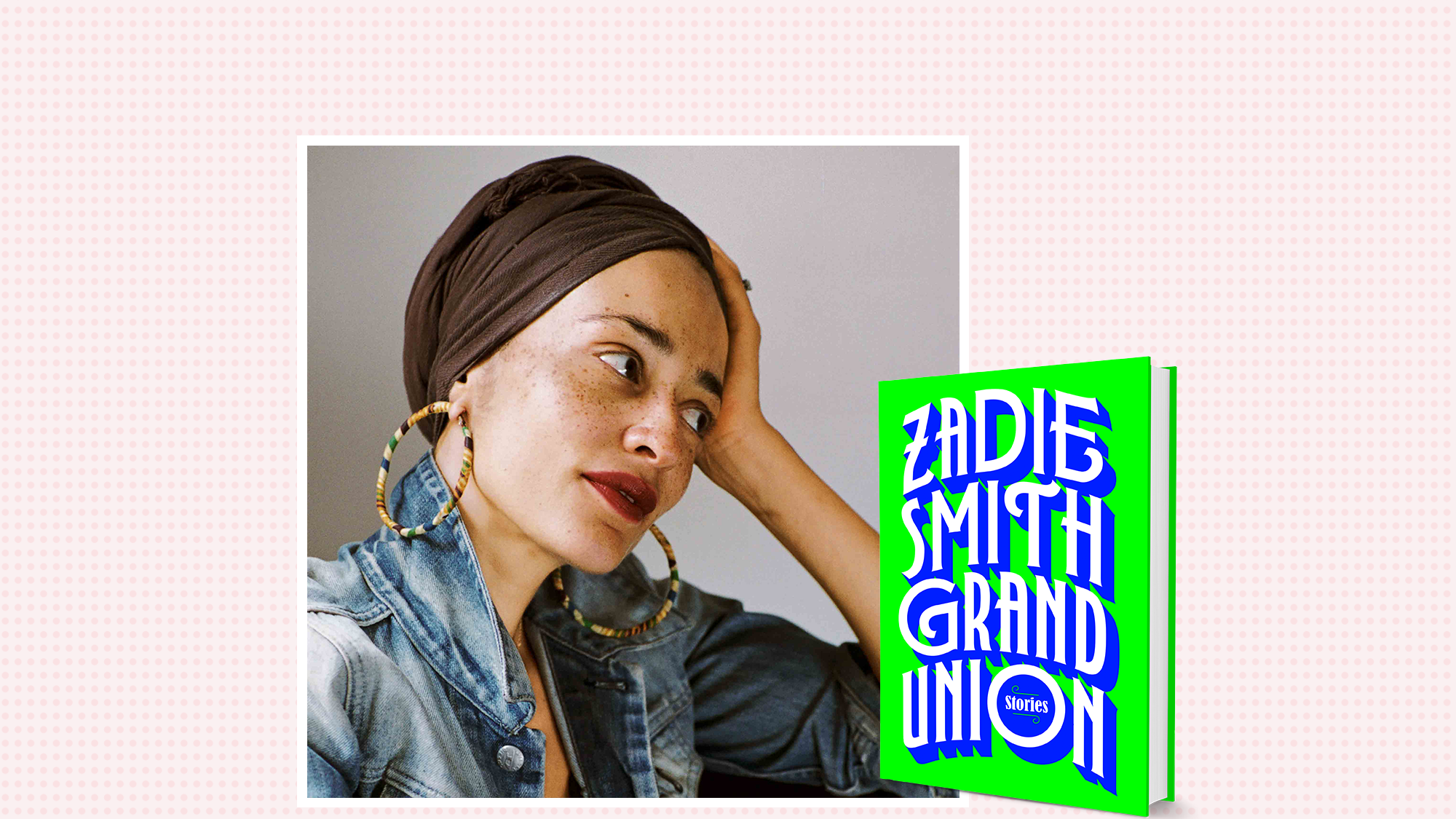

Zadie Smith's New Book 'Grand Union' Is Intensely Personal

The 43-year-old author talks perspective, identity, and required reading.

For Zadie Smith, summers in England and Ireland devoted to family leave little time for work. She returned home to New York last fall “full of beans”—ready to write—and the result is her first short-story collection, Grand Union, October 8. After not writing for a long time, she says, “when you finally sit down, you just want to write. And that's how I felt. I just suddenly had a little burst. Who knows why these things happen.”

Smith received worldwide acclaim at 23 for her first novel, White Teeth. In the 20 years since, she has published four novels and two collections of essays, most recently Feel Free in 2018. She teaches at New York University’s prestigious Master of Fine Arts (MFA) program in creative writing, where she was inspired to experiment with short stories after discussing them with her graduate workshop semester after semester.

At the moment, Smith is obsessed with gaining perspective on how technology is changing human behavior. That sounds like an ambitious summer reading project because it is. Here, the author discusses identity's relationship to creativity, owning bad writing, and why we should pay closer attention to the internet.

Marie Claire: Both this book and your last one feel intensely personal. When is a subject an essay or a short story?

Zadie Smith: For me, there's only writing. It can be done more or less effectively. Just because something's personal to me, intimate to me one way or another, it never means that it makes it good. I can feel something very strongly and still write very badly about it. Sometimes younger people think, “Oh, if I feel something very strongly and I write it very passionately, it will pass onto the reader.” In my experience, that's not true. What passes onto the reader is technique.

MC: There’s a story in Grand Union called “Lazy River,” which was originally published in the New Yorker. You mentioned in an interview that you and your family went to a lazy river and it felt like a metaphor.

ZS: Oh, yes. We were at a lazy river! I guess that's true. There's another way you could write that story, a kind of psychological story of marriage and children, but that's not what interested me about it. What interested me was the feeling of something, the metaphorical possibility of this river. I was with friends, and I don’t know if they would recognize that story as an account of their holiday. Two people can do exactly the same thing and have nothing like the same feeling about it. I'm always trying to find a general experience in something specific.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MC: The story “Kelso Deconstructed” is based around the last days of Kelso Cochrane, an Antiguan immigrant who was murdered in London in 1959. Why were you drawn to Kelso’s story?

ZS: I'm living in America and hearing about the deaths of young black men day in, day out. And sometimes for me, just the kind of writer I am, writing about things from a slant is more possible. Sometimes the feelings you have are too strong. The feelings I had about what was happening in America... I couldn't make them into the story. Sometimes you're just too angry or too upset and it's not easy to make fiction out of that kind of emotion. But Kelso is something from the past that I could process. There's been a lot of news in England about my mother and grandmother's generation of Jamaican immigrants, the way they're treated presently in England. So I had all my feelings about that too. And Kelso was the way to find somewhere to put all that emotion, yes, but in a controlled way.

A demonstration in Whitehall, London, organized by the Coloured People’s Progressive Association. The protesters carry posters and placards including a picture of Kelso Cochrane, a black man murdered in Notting Hill in 1959.

MC: How does living in America and England change your perspective when you're writing about either place?

ZS: I think of myself as somebody not at home, I suppose. Not at home anywhere, not at home ever. But I think of that as a definition of a writer: somebody not at home, not comfortable in themselves in their supposed lives, in their nation, in their bodies, in everything. There are lots of people who feel very certain about themselves, where they're born, what it means. I never felt that way. Moving between America and England is like a concrete manifestation of a feeling I've had all my life, of not really belonging anywhere. I don't think of that as a negative feeling. To me, it's creative. It's the people who feel that they belong very strongly who put the fear of God into me, to be honest.

MC: It's interesting that you feel like an outsider, especially because your work has been so widely accepted by the literary community.

ZS: Oh, I'm sure there are many people who hate it, but you can't really work thinking about that. You can only follow your own little path, which is necessarily narrow.

Writing isn’t cumulative. I say to my students, it's not as if writing books makes me a good writer. That's not how writing works. The possibility of writing a bad book is continually present for everybody, all the time. You start from scratch every time you start. That’s unfortunately the way it is. It's why you can say of your very favorite writers, “God, I hated that third one. Or God, that fifth one was awful,” because it's a risk every time. And the same insecurities and same anxieties remain. They never leave you. If they did, perhaps you'd write worse.

MC: The narrator of the story “Blocked” meditates on early success. You were first published at 23. What was that experience like for you?

ZS: I’ve tried to make the best of what I was given, not take it for granted and demonstrate somehow that I take it as seriously as it’s possible to take it. I don’t ever write anything slapdash or think, Oh, this will do. It may be bad, but I didn’t shortchange it in any way.

MC: Looking back just across your writing career, would you do anything differently?

ZS: I would always like to have read different books. There's plenty of time to write, really. But there's not enough time to read everything that's been written. There are different books I wish I had read as a child that would have made me a different writer than the one I am. What I try and do to remedy it is read widely now.

MC: What are you currently reading?

ZS: I just read The New Me by Halle Butler. It’s terrific. So funny. Right now, I'm reading the memoir of a Colombian writer, Hector Abad Faciolince. I really want to read outside of the Anglophone world. I've read enough English and American writing to last me a lifetime, so I'm interested in different writing, French writing particularly.

The thing I'm desperate to read is nonfiction. And particularly to understand the internet. There's a wonderful book called The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, which is 700 pages long. I don't think anyone who thinks of themselves as understanding the times or the internet or activism or anything else should do anything until they've read that book, because it's completely astonishing. That is taking up most of my time. If I could tell every reader about to buy my book to buy that one instead, I would.

KD: What expectations do you think our culture places on its writers?

ZS: I don't think Americans are too concerned with writers these days, are they? They've got many other things to be concerned with. It's probably not a very useful job. I see my job as trying to express how it feels to be alive, outside of dogma or argument or the things we think we should say—how it actually feels.

A version of this story originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of Marie Claire.

RELATED STORY